Smartphone apps help asylum seekers find their way

A Syrian father underwent a long journey to the Netherlands with the help of his smartphone. Currently living in Tilburg, he does not expect Syria to return to its pre-war state soon.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Hasan is one of almost 60,000 people who asked for asylum in the Netherlands last year. Hailing from Aleppo, Syria, he felt that his home was no longer safe and, eventually made a decision to flee to Europe. During the journey, Hasan relied on his smartphone for the purposes of communication and, for searching for information. His journey led to him Tilburg, Netherlands, where he is currently awaiting a verdict about the application for asylum.

“The future is dark because I know about politics and about history. And, I can understand and envision a lot of scenarios from the past, that it is going to be much worse.”

Hasan is a tall man in his forties, who has been raising his two children of thirteen and fourteen years alone for about a decade. In Syria, he worked as a human resources coach and consultant. However, the ongoing conflict in the country forced him to leave. This was to avoid facing the worsening of the situation. In fluent English, he states: “The future is dark because I know about politics and about history. And, I can understand and envision a lot of scenarios from the past, that it is going to be much worse.”

When considering where to go, he studied details about the asylum seeking process, as well as information about obtaining citizenship. He then decided on the Netherlands. In an interview, he described his parenting style when making this difficult decision:

“I was keen to persuade my children to support the decision to flee. I didn’t tell them, just go, I decided on behalf of you. No, I wanted them to believe in this decision because if they believe in it, they will have the efforts and they will be patient. Otherwise, they will never. They know that this is a good decision.”

Back to top

A twenty-day journey to the Netherlands with Google Maps

At the beginning of their journey, the family flew to Istanbul, where they stayed for a few days and then continued to Izmir. Eventually, they got into a small rubber boat heading to Lesbos. After four nights, they continued to Athens. Hasan has a cousin in the Greek capital and was able to spend almost a week at his place. “I just wanted to relax and to charge myself mentally, psychologically and spiritually before I suffered the rest of the journey,” he explains. Then, the family continued through the Balkans to Austria.

“Upon the arrival to Austria, I decided to leave the group of the asylum seekers I was travelling with and go by my own. So, I took the train, with my son and daughter, to the west of Austria, Salzburg. I spent two nights there. Then, I completed it,”

Hasan continues.

The journey took twenty days. During these, Hasan’s smartphone was an invaluable help to him. “I used Google Maps and even the routes to find the way. In Istanbul, when I was meeting my friend, but also in Austria,” he says. He also used the smartphone for searching for various information. “I had to choose a hotel in Austria. I could compare which hotel was the best for me, with prices. I also looked into how to go from Austria to Holland,” Hasan elaborates on his smartphone usage during the journey.

Back to top

Communication on the phone and with laptop

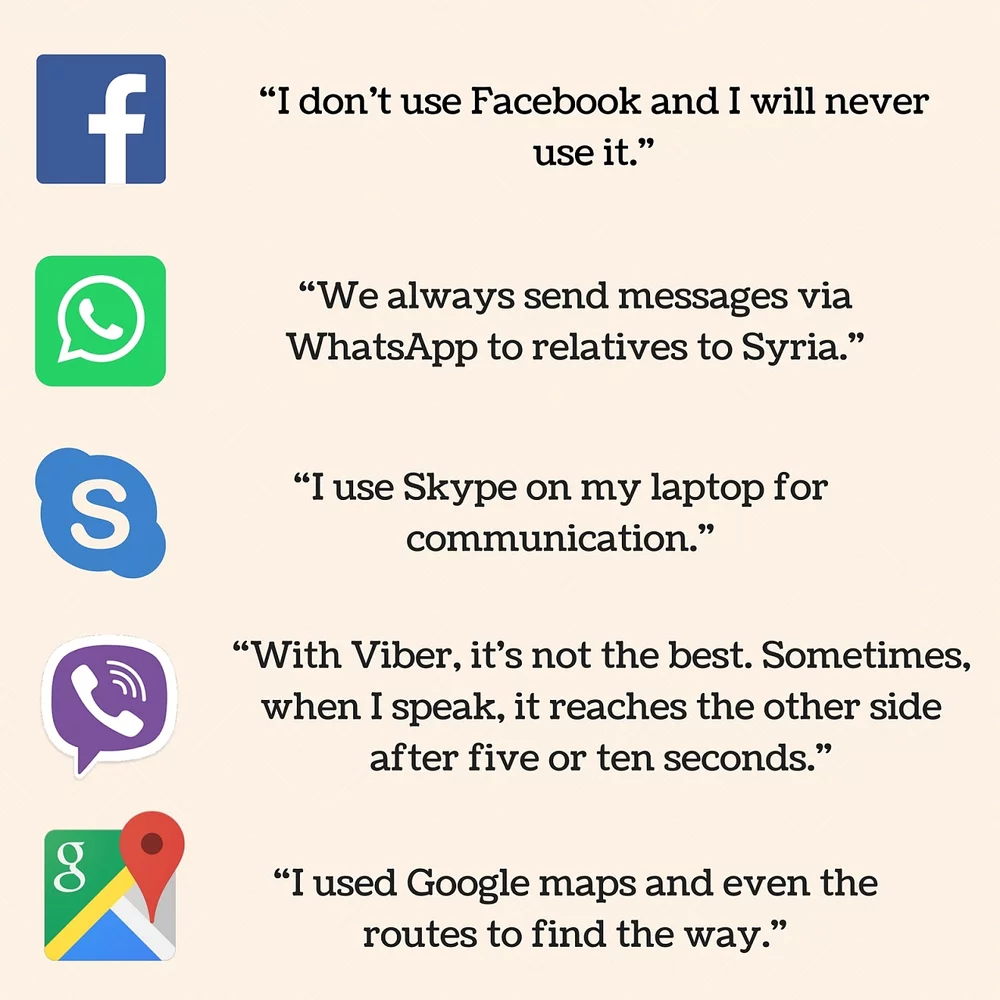

Hasan also uses his phone for its primary purpose- communication. His relatives still live in Syria and he keeps in contact with them. However, this communication is frequently troublesome. “Sometimes we have regular phone calls, sometimes we use Viber, but it is not the best because we cannot hear each other. Sometimes, when I speak, it reaches them after five or ten seconds,” he reports what problems he is facing in communicating with the relatives. “So we always send messages via WhatsApp,” he adds.

Apart from the smartphone, Hasan also uses a laptop, where he employs another app for communication - Skype. “I feel more comfortable over my laptop than my mobile phone,” he points out. What Hasan does not use are the social network sites. “I don’t use Facebook and I will never use it. I will not say why but I will never. And I don’t have Twitter or Instagram.”

Prospects for the future

In Tilburg, Hasan is staying in a refugee center with around five hundred other asylum seekers. Except for Syrians, there are people from India, China, Eritrea or Somalia. Hasan says that:

“Those countries, they have their own troubles. Maybe they are afraid or maybe they are poor. But, I think, not only for the Dutch government but also for all of the European governments, that might not be enough. If all the poor people want to move, there will be troubles in their own nations,”

The conditions Hasan’s family currently lives in are modest. At present, he and his children are staying in one room, sharing a bathroom with other asylum seekers. The availability of Wi-Fi connection in the building makes it easier to keep in touch with relatives and friends, as well as to follow the news. Hasan does not see the future of Syria in bright colors. “I don’t expect the war to end before five years. And, after the end of the war, we have another war, which is a social war and political parties and the parliament and elections and…

“When people stay under war for a long time, they do accept violence and hating others as a default.”

Hasan explains why he may not be able to return to Syria soon. “When people stay under war for a long time, they do accept violence and hating others as a default.” However, he hopes that he and his children will be able to maintain their cultural heritage, while integrating into a new country. “The culture is intangible heritage. So when you keep it, it enriches your life. I think it is more healthy to belong to both of the cultures,”he reasons. To the question whether he wants to work if he gets the refugee status, Hasan answers with a simple question: “I will ask this back to you, what do you think?”

Note: The editorial staff knows the identity of the respondent. His surname was not used to protect his privacy.

Back to top