Trump's Executive Order 14224 Language policy or linguicism?

March 1, 2025, President Donald Trump by Executive Order designated English as the official language of the United States. Having a common language is believed to strengthen a country's cohesion and unity, it, however, also means the exclusion of other languages and the denial of the people that use them as legitimate speakers or even citizens. This article discusses the EO and the critique it raised and puts all of this in a historical American and European perspective. It also presents some requirements for developing integral language policies in times of globalization and superdiversity.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

March 1, 2025, President Donald Trump, the man who enriched the English language with a word – covfeve – that nobody had ever heard of before (Blommaert, 2021), has signed an Executive Order (EO 14224) declaring English as the official language of the United States. Among an unprecedented number of EOs, ranging from ‘Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government’ to ‘Ending Procurement and Forced Use of Paper Straws’, this more mundane sounding EO could easily go unnoticed. But that would be a mistake. A main argument for declaring one specific language as the only official language of a specific territory is the idea that this language policy measure contributes to the territory’s power and development. Using a common language is believed to strengthen a people’s cohesion and unity. Opting for one language as an official language, however, at the same time, at least implicitly, means the exclusion of other languages and the denial of the people that use these languages as legitimate speakers or even citizens.

In this article I will first present the text of the EO on designating English as the official language of the United States, then deal with the strong and broad critique the EO met, refer to a bit of (forgotten) history and finally look at the position of ‘official languages’ in Europe and, more specifically, in the Netherlands. I end the article with some requirements for developing integral language policies in times of globalization and superdiversity.

Back to top‘Designating English as the Official Language of The United States’

The main text of the Executive Order (section 1) runs as follows:

“Section 1. Purpose and policy. From the founding of our Republic, English has been used as our national language. Our Nation’s historic governing documents, including the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution have all been written in English. It is therefore long past time that English is declared the official language of the United States. A nationally designated language is at the core of a unified and cohesive society, and the United States is strengthened by a citizenry that can freely exchange ideas in one shared language.

In welcoming new Americans, a policy of encouraging the learning and adoption of our national language will make the United States a shared home and empower new citizens to achieve the American dream. Speaking English not only opens doors economically, but it helps newcomers to engage in their communities, participate in national traditions, and give back to our society. This Order recognizes and celebrates the long tradition of multilingual American citizens who have learned English and passed it to their children for generations to come.

To promote unity, cultivate a shared American culture for all citizens, ensure consistency in government operations, and create a pathway to civic engagement, it is in America's best interest for the Federal Government to designate one – and only one – official language. Establishing English as the official language will not only streamline communication but also reinforce shared national values, and create a more cohesive and efficient society. Accordingly, this order designates English as the official language of the United States.”

Back to topCritique

Among the first of the many organizations that issued their critique on the Executive Order were TESOL, the international association of Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages, and the Linguistic Society of America, a scholarly society that aims at advancing the scientific study of language. According to TESOL’s statement of March 4:

“This EO establishes U.S. federal policy guidance that leads to discriminatory practices against multilingual learners of English, in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ; by rescinding the 2000 EO 13166, which directed federal agencies to improve access for individuals with limited English proficiency, this EO creates barriers to full and equal participation in public services, including education, for the millions of multilingual learners of English living in the United States.”

Already in the early 2000s, TESOL campaigned against English-only legislation initiatives of the Official English Movement because the myths produced by this movement “remain just as relevant in our current context as they were twenty years ago. Designating English as the official language of the United States will not promote unity, empower multilingual learners of English, or promote a cohesive and efficient society.” Instead TESOL proposes to, in English language teaching, stick to recognition and celebration of “the diversity of assets and voices of each learner and their family.”

Also, the Linguistic Society of America strongly rejects the EO. It does so by formulating a well-argued alternative position to the four statements that are central to the EO:

- The United States has always been a multilingual country, and this gives it strength.

- Citizens of the US and of all democracies inevitably have different linguistic ways of navigating their lives, and enforced monolingualism never achieves national unity.

- "Official English" policies do not improve economic prospects for those who arrive in the US speaking another language, nor do they improve communication for those who live in multilingual communities.

- Supporting and promoting multilingualism makes a nation stronger, not weaker.

The LSA then concludes with a call to action for a multilingual society, not a monolingual one:

“When this Executive Order is viewed in conjunction with other recent Executive Orders, including the January 20, 2025 Executive Order, “Protecting the American People Against Invasion,” it appears designed in service of broader anti-immigrant goals, including the erasure of the history and culture of millions of people in the United States who are not monolingual English speakers. Previous attempts to create a single official language for the United States have all been rejected. We ask: if the United States has not needed an official tongue for more than 200 years, why would we need one now?”

What these and many other critical assessments of the EO have in common – see for example the statements by Joint National Committee for Languages NCL-NCLIS, the Center of Applied Linguistics CAL, The Japanese American Citizens League JACL, American Association for Applied Linguistics AAAL – is that they criticize the fact that it refers to “multilingual American citizens” but, most ironically, celebrates this multilingualism mainly as a preliminary stage in acquiring and using English as part of a government instigated top-down family language policy for “new Americans” – as opposed to the regular “citizenry” it seems – with a task and a promise: learn English and you will achieve the American dream. This ‘promise of language’, as it is called by Kraft and Flubacher (2020), however, hardly ever materializes in getting access to education or employment if it isn’t supported by political and societal infrastructures that enable newcomers and oldcomers in a country to really participate in second language learning trajectories (Hooft, 2025). And such infrastructures are hardly ever in place. In addition, the EO contains a rather straightforward formulation of the so-called do ut des principle: we give you English as an official language – read: we enforce English upon you – and in return you give back to society. Again, without creating real conditions to make societal participation possible.

It sounds as a bad joke to read in the EO that it “recognizes and celebrates the long tradition of multilingual American citizens who have learned English and passed it to their children for generations to come”, i.e., who transitioned their multilingual families into monolingual ones. This might sound new, but we should remember that transitional bilingual education, as enshrined in the 1968 Bilingual Education Act (that was terminated in 2000) – even if it is often presented as a policy measure that promotes multilingualism, if it is successful, eventually leads to monolingualism.

They have languages that nobody in this country has ever heard of (Donald Trump)

Finally, the EO is more than just an act of language policy. As I argued elsewhere (Kroon, 2022), in most cases, language policy is a means to also reach another goal than “to influence the behavior of others with respect to the acquisition, structure, or functional allocation of their language codes”, as Cooper’s (1989: 45) definition of language policy goes, be it political, societal, ideological, cultural or economic. This ‘other goal’ also includes advertising a certain vision on language and languages. In the case of EO 14224, this vision becomes manifest in Trump’s speech after signing the order that can be found in an Al Jazeera feature on YouTube. After the voice-over’s opening statement, “For president Trump, signing the executive action addresses his longtime complaint of foreigners diluting the English language in the United States,” Trump makes his vision on language very clear: “It’s the craziest thing. They have languages that nobody in this country has ever heard of.” In other words, there is English, and there are other languages that we have never heard of, that therefore do not count as languages, that should not receive any governmental support, and that should be done away with because they dilute the English language in the US. In the early 1990s Skutnabb-Kangas and Phillipson (1995) introduced the concepts of linguicide and linguicism. They define linguicide as "the extermination of languages, an analogous concept to (physical) genocide"(p. 83) and linguicism as "ideologies, structures and practices which are used to legitimate, effectuate and reproduce an unequal division of power and resources (both material and immaterial) between groups which are defined on the basis of language [---]. Linguicism can relate to both languages and their speakers. It precedes (but does not necessarily lead to) linguicide and/or language death." (p. 83) In their taxonomy of policies that a state can adopt towards minority languages, Skutnab-Kangas and Phillipson (1994, p. 2211) distinguish between (1) attempting to kill a language, (2) letting a language die, (3) unsupported coexistence, (4) partial support of specific language functions, and (5) adoption as an official language. By signing the EO, President Trump, not only for ‘languages that nobody in this country has ever heard of’ but implicitly also for a language like Spanish that has some 40 million speakers in the US, opts, for ‘unsupported coexistence’ – in a benevolent reading, that is – or letting these languages die in favor of English. Both positions, according to Skutnabb-Kangas and Phillipson are “covertly linguicidal” (p. 2211) but at the same time involve an agent in causing the death of a language. As such, the EO is a textbook example of Planning Language, Planning Inequality (Tollefson, 1991) that contributes to unravelling the often hidden and messy ambitions of policy makers.

Back to topThe policy not to have a policy

The origins of American multilingualism, in addition to the manifold native American languages, can be traced back to it being a country where in the 18th century all kinds of mainly European immigrants lived and worked together and eventually founded what is now the USA. Executive Order 14224 explicitly refers to the Declaration of Independence (1776) as one of the United States’ historic governing documents being written in English. That’s true, but, as has been nicely shown by Geerts (1979), the Founding Fathers of the United States, just like their colleagues in revolutionary France, were very well-aware of the fact that the cultural and linguistic diversity of the various groups that would be included in the new state, could easily lead to communication problems. Therefore, in the beginning they published their ideas and decrees in the most important languages, English, French, Spanish, German. Even if the majority spoke English and even if they thought about making English their national language, they decided not to because doing so was found to conflict with their ideal of freedom. They therefore decided “not to designate a national tongue” and opted for “a policy not to have a policy” as Heath (1976, p. 9-10; in Geerts 1979) put it, that is the recognition of equality of all languages and societal multilingualism.

As we know, in the end, as probably expected or even hoped also by the Founding Fathers, English prevailed as the main language of the United States – and beyond.

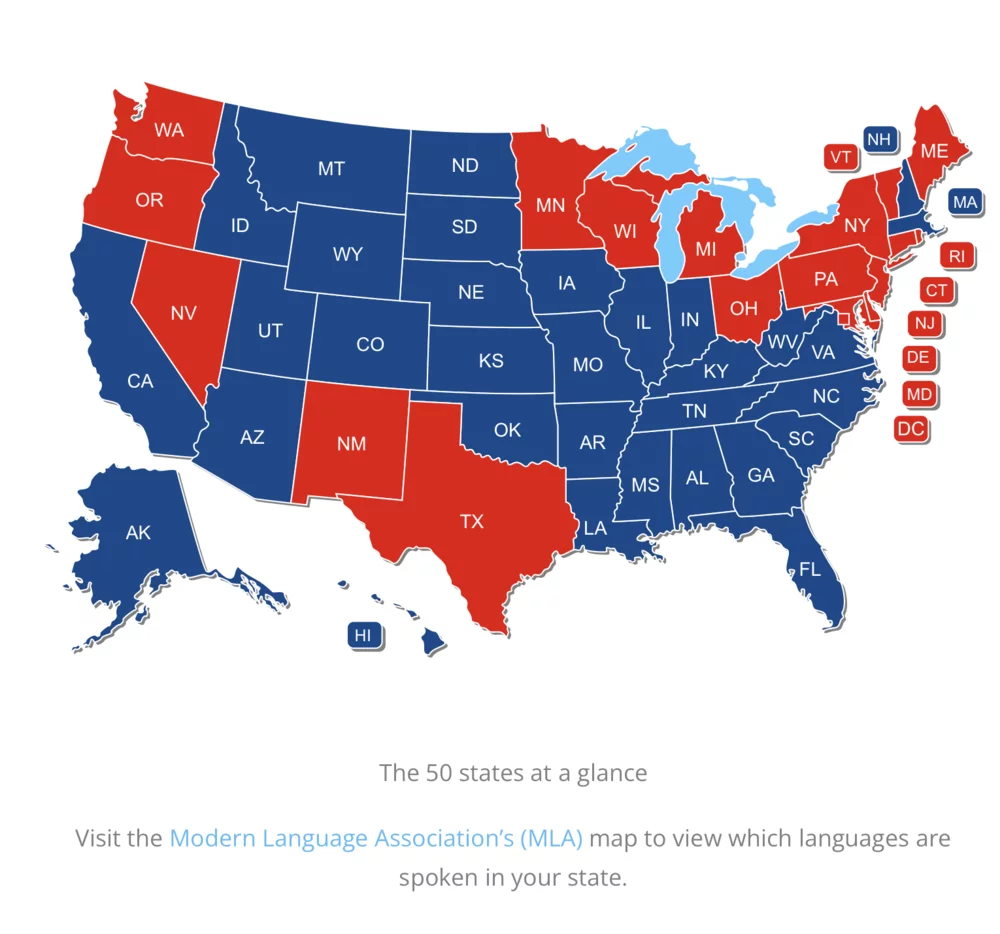

The ‘policy not to have a policy’, leading to not designating English as the official language of the United States, already in the early 1900s led to discussions, anxiety, and protests voiced by the so-called English-only or Official English movement, strongly promoted by U.S. English, “the nation’s oldest, largest citizens’ action group dedicated to preserving the unifying role of the English language in the United States” that was founded in 1983. At a state level English-only political and legislative action over the years led to 32 states now having official English legislation. March 2025, EO 14224, with just one presidential signature, made the map below, published by ProEnglish “the nation’s leading advocate of official English”, all-blue.

Back to top

The European experience

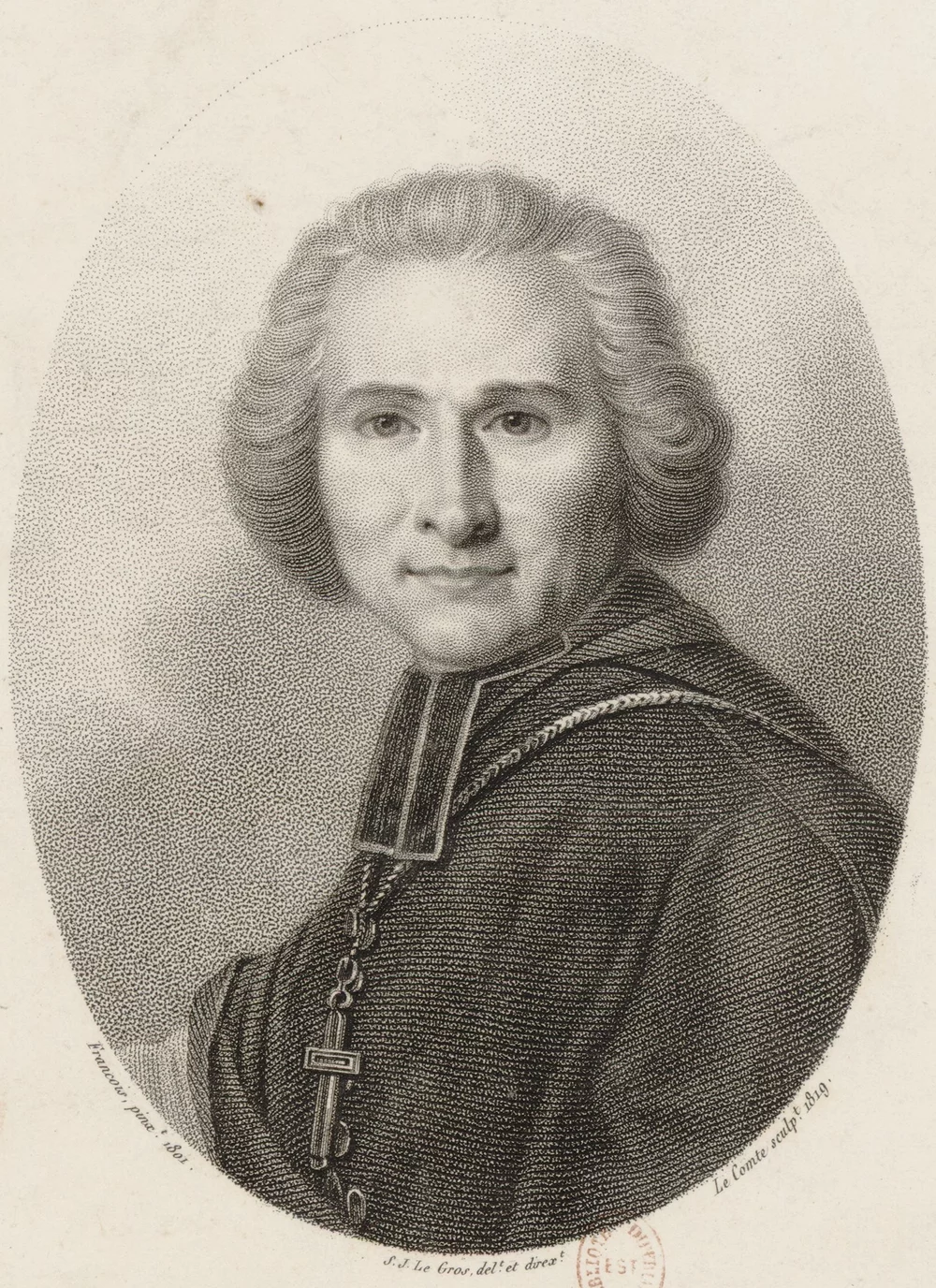

Where the Founding Fathers of the United States decided not to declare English as their official or national language, the French revolutionaries originally had the same idea. They, also, in the beginning, intended to publish their laws and measures not only in French but also in the various regional languages of the country. They however quickly discovered that there was more linguistic variety in France than they had expected. Therefore, in 1790, priest and revolutionary politician Henri-Baptiste Grégoire was commissioned to investigate the linguistic diversity in the country. Geerts (1979, p. 8) refers to the questionnaire that Grégoire used in his investigation as probably the first language policy enterprise in modern Europe. However, where Grégoire initially aimed at only mapping linguistic diversity in France in order to enable the revolution to reach as many citizens as possible, in his final report that was published in 1794 he formulates as a conclusion “la nécessité et les moyens d’anéantir les patois et d’universaliser la language française” (De Certeau, Julia, & Revel, 1975, p. 300) leading to the victory of French as a national language. Where using also regional languages was originally motivated by the revolutionary principle of égalité, on second thoughts using only French was motivated by the principle of liberté, that is, freed from the old feudal system and the old languages that would hinder citizens to really participate in the new times to come. As Geerts put it: “The new language defines the new world, determines the new future; the new language is the revolution.” (p. 10). In this context it is remarkable that the Académie Française, an institution of the Ancien Régime that was founded in 1634, was kept in place as the custodian of French vocabulary and syntax and the global promotion of French.

Taking a great leap forward, we can conclude that France is among the European countries that has constitutionally anchored French as its national language. As of June, 25 1992, Article 2 of its Constitution says: “La langue de la République est le français.” Having a constitutional article declaring one and only one language as its national language, France is in good – or bad – company. The EFNIL overview of language legislation in Europe shows that, just like France, the vast majority of European countries have a constitutional article and/or language law that defines the country’s official or national language. As another example, I quote the Hungarian constitution that states: “There is just one national language in Hungary: Hungarian.”

A fatherland needs a mother tongue

Such statements are a clear reflection of the 19th century period of European nation state formation, based on what Blommaert (2011, p. 244) referred to as the Herderian vision in which "language coincided entirely with culture, and this duo defined the essential identity of a ‘people’ [---]. Nations, according to Herder’s political followers, had to be built on the solid foundations of such single language-culture identities. The nineteenth century saw the birth of numerous such monolingual and monocultural nation-states [---]. This monolingual-monocultural model of the ideal nation-state was in fact the blueprint for the Modernist state [---] that imposed a standardized ‘national’ language on the totality of public social life, i.e. across the whole spectrum of social arenas that structure an individual citizen’s life, starting from a monolingual education system and stretching into public administration, the press and economic life." As the slogan goes: a 'fatherland' needs a 'mother tongue' and 'mother-tongue education' is assigned to create citizens that fit this ideal of homogeneity (Ahlzweig, 1994; Gardt, 2000; Kroon, 2003). Of course, all three, the idea of one homogeneous people, one homogeneous territory, and one homogeneous language, already then, but certainly now, in times of globalization related mobility and superdiversity, are a matter of what was Green and Erixon (2020, p. 262) have called “empirical fiction”. Needless to say that designating a language as “official” or “national” doesn’t wipe out the empirical fact of language diversity that is the rule rather than the exception globally.

Back to topThe failed Constitutional anchoring of Dutch in the Netherlands

The Netherlands, until now, is among the very few countries that do not have a constitutional article enshrining their most spoken language as the official language of the state. According to the overview by Brand and Van der Sijs (2007), in 1830, after the breakup of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and Belgium, King Willem I, by royal decree, declared Dutch the official language of all Dutch provinces. This position, however, wasn’t included in the new Constitution of 1848 that made the Netherlands a parliamentary democracy. In the years that followed, main points of parliamentary discussion on language matters included the position of Dutch as a language of instruction in education, the funding of the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal (Dutch dictionary), establishing an official orthography, the position of Dutch dialects and Frisian, (especially after the Second World War) a plea for using “pure” and “proper” Dutch, and strengthening the position of Dutch internationally as well as in the Netherlands. It is only in the 1990s that members of parliament took the initiative to put the position of Dutch as an official language on the political agenda.

March 20, 1991, members of parliament van Middelkoop (GPV, protestant-christian party) and Mateman (CDA, christian-democratic party) proposed a motion in which they asked the government, in view of the expected further European integration, to investigate the possibilities of including the use of the Dutch language in a law or the Constitution as the language of education, government, and jurisdiction (Tweede Kamer 1990-1991, 21 427, nr. 12 and 14). In October the Ministry of the Interior published the results of this investigation. The document says, among other things: “The Dutch Constitution does not contain a provision that establishes an official language. It can be stated, however, that the notion that Dutch is the official language in the Dutch territory of the Kingdom is part of unwritten law; the fact that this rule is unwritten can be explained by the self-evidence of this notion.” (TK 1991-1992, 21 427, nr. 20, p. 2) The Middelkoop/Mateman motion was intensively discussed and finally received approval in parliament (be it in a slightly adapted wording). But after that not much happened. The government kept silent and the motion, although accepted, never materialized in legislation.

October 3, 1995, members of parliament van Middelkoop (GPV) and Koekoek (CDA) gave it another try and put the issue back on the political agenda, this time by taking the initiative to propose a law to add an article to the Constitution saying: “The promotion of the use of the Dutch language is a matter of concern of the government.” (TK 1995-1996, 24 431, A) The Dutch language should be promoted, so the argument runs, (1) because it is under pressure of English due to increasing internationalization, (2) because it is at risk of losing its official status in the EU in the event of the EU’s possible expansion, and (3) because there is currently insufficient regulation as to which language the government should use in dealings with citizens. In the April 1997 parliamentary discussion of the proposal, voices against the proposal were in the majority. The Minister of the Interior Dijkstal (VVD, liberal party) said that the government didn’t see the need for including Dutch in the Constitution: “Firstly, the cabinet feels that its inclusion in the Constitution is of very symbolic significance, which does not fit in with the idea that the Constitution should be sober. Secondly, the cabinet believes that the position of the Dutch language is sufficiently guaranteed in our legal system and that legislation and case law also show that Dutch is the language of administrative and legal transactions, thirdly, that the government does not expect that a provision in the Constitution can actually contribute to strengthening the position of Dutch in international transactions (TK 10 April 1997, 68-4935). In the discussion also reference was made to the fact that a Constitutional article for strengthening the international position of Dutch could be considered as potentially limiting the position and further development of Dutch regional languages and dialects, like Frisian, Dutch Low Saxon and Limburgian, recognized under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages that had been signed by the government already in 1992 and was ratified by parliament in 1996. April 22, 1997, a majority of parliament voted against the proposed law to make the Dutch language a matter of concern of the government.

In the February 2007 Coalition Agreement (TK 2006-2007, 30 891, nr 4) for a new government of CDA, PvdA and ChristenUnie (protestant-christian party), the Dutch language issue was again included. Under the heading ‘Art and culture’ it stated: “The government promotes the simple and careful use of Dutch as an administrative language and as a language of communication, and to this end it establishes Dutch in the Constitution, without infringing upon the legal recognition of (the use of) the Frisian language.” In their advice on this statement, the Council of State of the Netherlands (TK 2007-2008, 31 570, nr. 3) concluded that the twelve-year duration of the discussion on this issue in parliament, in their view puts the need for a constitutional anchoring of Dutch into perspective. The Council therefore advised against including Dutch in the Constitution. And again, nothing happened.

If we look at the arguments put forward by the proponents of including an article on the Dutch language in the Duch law or Constitution, I think it is remarkable that we don’t see any explicit reference to a felt societal need for safeguarding Dutch as the language of the Netherlands in an era in which Dutch society, as a consequence of labor migration, decolonization and the arrival of refugees and asylum seekers from all over the world had become truly multilingual. The only reference to other languages than Dutch is about the position of Frisian and the main argument to protect Dutch seems to be its minority position in the context of the European Union. Only in the Coalition Agreement we find the argument that the Dutch language is under pressure due to what rather unspecific is called ‘increasing internationalization’.

Do you want to legally regulate that only Dutch may be spoken in government buildings? (Wilders, Brinkman, Fritsma)

Finally, reading trough the 2007 Parliamentary Proceedings, I accidentally came across a series of questions to the government “on the desirability of legally establishing the obligation to speak Dutch in government buildings”, submitted November14, 2007, by members of parliament Wilders, Brinkman and Fritsma (PVV, right wing populist party for freedom) clearly taking migration-related linguistic diversity in the Netherlands as their starting point (TK 2007-2008, Aanhangsel, 1789). The questions were the following: (1) Are you aware of the reports ‘Irritation about Turkish-speaking politicians’ and ‘Politicians must speak Dutch’? (2) Do you agree that it is undesirable for politicians to speak Turkish during council meetings? If not, why not? (3) Do you agree that only Dutch should be spoken in government buildings? If not, why not? (4) Do you want to legally regulate that only Dutch may be spoken in government buildings? If so, do you want to start the legislative procedure as soon as possible? If not, why not? The answer of the minister was rather straightforward: It is a matter of good manners to use in meetings a language that everybody can understand. Still, it can be necessary to sometimes also use a foreign language when having a meeting. In conclusion her answer to the fourth question was a clear and simple ‘no’.

Back to topLanguage policy development

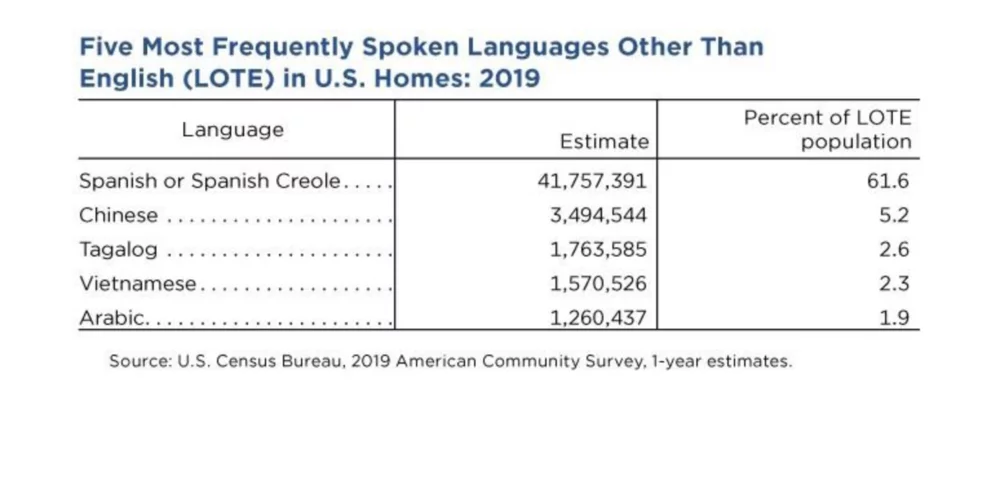

English in the United States, just like French in France, German in Germany, and Dutch in the Netherlands, isn’t a language under threat. Even if, according the 2019 American Community Survey, more than a thousand languages are currently spoken in the US, English is by far the most spoken first or second language – 78% of the population speaks only English. And the number of people speaking English increased from 187.2 million in 1880 to 241 million in 2019. At the same time also the number of people in the US who speak a language other than English at home increased: it nearly tripled from 23.1 million (about 1-in-10) in 1980 to 67.8 million (almost 1-in-5) in 2019.

Why then would there be a need to designate English as the official language of the United States? Let me here return to what I said earlier on “the other goal” of language policy. President Trump’s EO 14224 isn’t only about language. Just like the successful language policy of the French Revolution was not only about language but also about creating national unity, and just like the failed attempts to anchor Dutch in the Constitution of the Netherlands was not only about language but also about the position of the Netherlands in a growing European Union, also Trump’s EO isn’t only about language but also about introducing a type of nationalism that is foreign to the US. It shows America’s cultural patriotism – we are all migrants – developing into an ethnocultural nationalism in which cultural features such as western language, religion, ancestry, and tradition prevail. Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese, Arabic and many other languages “that nobody has ever heard of” (voce Trump) don’t fit this picture and must be excluded. This process started with the successful legislative actions of the English-only movement in a growing number of states that mainly aimed at building a symbolic wall against, first of all, Spanish and also other migrant languages by declaring English as the official language of the state. It is reported that in some states this symbolic and non-prohibitive wall turned into reality, for example in Colorado where “an elementary school bus driver prohibited students from speaking Spanish on their way to school after Colorado passed its legislation.” (Gibson, 2004, p. 12)

Exclusion of languages as legitimate means of communication basically leads to the exclusion of people who speak these languages as legitimate citizens. That exactly, I think, was the intention of Dutch Minister of Integration Verdonk (VVD) when she proposed in an interview in 2006 the idea to introduce a rule of conduct that in the public domain only Dutch would be allowed as a language of communication. January 17, 2006, the City of Rotterdam had already formulated a code of conduct that said in article 2: “We inhabitants of Rotterdam use Dutch as our common language.” This article included three elements: “(1) Dutch is the common language of Rotterdam. In public, we speak Dutch – at school, at work, on the street and in the community center. (2) It is our responsibility to have a sufficient command of Dutch, or otherwise to learn it. (3) We raise our children largely in Dutch, so that they have plenty of opportunities in our society.” The formal status of such code of conduct, however, and the legality of any ban on speaking languages other than Dutch in the public domain, turned out to be rather unclear and one day after the interview, the Minister already nuanced her proposal. Speaking another language is fine, the Minister said on the News, but those who want to stay here must use the Dutch language as much as possible.

The quality of a language policy should be judged not in terms of what it says about the majority language but rather in terms of what it says about minority languages

All the above is not to say that it wouldn’t be relevant for a country to develop a language policy. In doing so, however, a few basic points are important to consider (see also Kroon, 2025).

Firstly, it is important to realize that language policy is never a stand-alone but always part of a more general policy framework. Such framework requires agreement on a society’s underlying norms and values regarding the object of policy making. In our case this is about taking a position in the debate about ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity. That is, opting for a multiethnic, multicultural, and multilingual perspective as a starting point for language policy development or sticking to an outdated mono-everything ethnocultural nationalism. The latter perspective, be it in a somewhat mitigated form can be found in the attempts of Dutch members of parliament to protect Dutch in a constitutional article and it leads to what happened in Executive Order 14224.

Secondly, for developing a language policy, it is important to think about the definition of language as an object of that policy. Traditionally, language policy mainly is about ‘language’ as a monolithic, standardized, and fixed entity (language as a noun) and doesn’t deal with ‘languaging’, i.e., the way in which people deal with the elements and features of all languages and language varieties in their language repertoires (language as a verb) (Blommaert & Rampton, 2016). The latter perspective, that fits a multilingual ideology, leads to opting in language policy development for what I would like to call a usage-based approach. For the US and the Netherlands this would mean not only including in an integral design of language policy the (historically) most spoken language or languages of the country, but also varieties of these languages, as well as regional and/or native or immigrant languages. The quality of a language policy should be judged not in terms of what it says about the majority language but rather in terms of what it says about minority languages. In a usage-based approach, an executive order designating one and only one language as the official language of a country, aiming at annihilating other languages, would be impossible. The responsibility for such an integral language policy design could be given to one ministry – in the Netherlands for example the Ministry of the Interior is responsible for language matters - but it will be clear that in addition also Ministries of Education (as long as it exists in the US), Integration, Foreign Affairs or Welfare will have to contribute when it is about language because language permeates all sectors of society.

Thirdly, it is important to consider that a given language policy is always connected to a specific chronotopic context (Kroon & Swanenberg, 2020). A policy might well be developed at one point in time, but its implementation will most certainly take place in continuously changing contexts. Therefore, approaches or recommendations that may seem effective and relevant at one point in time may become less relevant or even obsolete later. I think the originally multilingual policies of the American and French revolutionaries not to opt for just one language are a clear case in point here: in the post-revolutionary years societal developments led to the monolingual monopoly of English and French respectively.

Fourthly and finally, apart from a specific chronotopic context that potentially hampers the effectiveness of language policies, there is another potentially disturbing aspect. This is the top-down/bottom-up divide in policy making, referring to the empirical fact that people’s bottom-up language practices often appear to be very different from top-down language policies in officially concluded policy documents (Johnson, 2013). A solution to this problem can be found in foregrounding the agency of language users in language policy development (Ricento & Hornberger, 1996) in such a way that they are all, irrespective of their languages, considered legitimate speakers and citizens, making them subjects rather than objects of policy making, as in President Trumps nationalist, monolingual, top-down Executive Order 14224 that is totally at odds with America’s sociolinguistic reality.

Back to topReferences

Ahlzweig, C. (1994). Muttersprache – Vaterland. Die deutsche Nation und ihre Sprache. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Blommaert, J. (2011). The long language-ideological debate in Belgium. Journal of Multicultural Discourses 6(3), 241-256. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2011.595492

Blommaert, J. (2021). Sociolinguistic restratification in the one-offline nexus: Trump’s viral errors. In M. Spotti, J. Swanenberg, & J. Blommaert (eds.), Language Policies and the Politics of Language Practices (pp. 7-24). Cham: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-88723-0_2

Blommaert, J. & B. Rampton (2011) Language and superdiversity. In K. Arnaut, J. Blommaert, B. Rampton, & M. Spotti (eds.), Language and Superdiversity (pp. 21-48). New York and London: Routledge.

Brand, C.J.M., & van der Sijs, N. (2007). Geen taal, geen natie: parlementaire debatten over de relatie tussen de Nederlandse taal en de nationale identiteit. Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 9, 43-56. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/2066/44191

Cooper, R. L. (1989). Language Planning and Social Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Certeau, M., Julia, J. & Revel, J. (1975). Une politique de la language. La Révolution française et les patois: l’enquête de Gréegoire. Paris: Gallimard.

Gardt, A. (ed.) (2000). Nation und Sprache. Die Diskussion ihres Verhältnisses in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Geerts, G. (2979). Nakaarten en vooruitzien: een taalpolitieke voorbeschouwing. Toegepaste Taalwetenschap in Artikelen 6. Taalpolitieke kwesties in Nederland. Handelingen van de Anéla-studiedag op 24 maart 1979 in Eindhoven.

Gibson, K. (2004). English only court cases involving the U.S. workplace: The myths of language use and the homogeneization of bilingual workers’ identities. Second Language Studies 22(2), 1-60. Retrieved from https://www.hawaii.edu/sls/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Gibson.pdf

Green, B. & Erixon, P.-O. (2020). Understanding the (post-)national L1 subjects: Three problematics. In B. Green & P.-O. Erixon (Eds.). Rethinking L1 Education in a Global Era (pp. 259-285). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55997-7

Heath, S.B. (1976). A national language academy? Internation Journal of the Sociology of Language 11, 9-43.

Hooft, H. (2025). To School or Not to School? Practices, Spaces and Appraisals of Adult Migrants’ Language and Literacy Learning in Antwerp (Belgium). Doctoral dissertation KU Leuven (forthcoming).

Johnson, D. C. (2013). Language Policy. New York: Palgrave McMillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137316202

Kraft, K., & Flubacher, M.-C. (2020). The promise of language: Betwixt empowerment and the Rrproduction of inequality. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 264, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2020-2091

Kroon, S. (2003), Mother tongue and mother tongue education. In: J. Bourne, & E. Reid (eds.), Language Education. World Yearbook of Education 2003 (pp. 35-48). London: Kogan Page.

Kroon, S. (2022). The other goal in language and information policies. Diggit Magazine, 8-9-2022.

Kroon, S. (2025). Language diversity, policy and practice. Five case studies. In Festschrift Jan Blommaert . Bristol: Multilingual Matters. (forthcoming)

Kroon, S. & J. Swanenberg (eds.) (2022). Chronotopic Identity Work; Sociolinguistic Analyses of Cultural and Linguistic Phenomena in Time and Space. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788926621

Ricento, T. & N. Hornberger (1996). Unpeeling the onion: Language planning and policy and the ELT professional. TESOL Quarterly 30(3), 401-427.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. & Phillipson, R. (1994). Linguicide. In The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (pp. 2211-2212), Pergamon Press & Aberdeen University Press. Retrieved from from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315698050_Linguicide

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. & Phillipson, R. (1995). Linguicide and Linguicism. In R. Phillipson & T. Skutnabb-Kangas, Papers in European language Policy (pp. 83-91). ROLIG papir 53. Roskilde: Roskilde Universitetscenter, Lingvistgruppen. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316622633_Linguicide_and_Linguicism

Tollefson, J. W. (1991). Planning Language, Planning Inequality. Language Policy in the Community. London and New York: Longman.

Back to top