SoundCloud & White Iverson: Breaking Free From The Prerogative Industrial Tyranny

This essay examines SoundCloud's impact on global music, showing the shift from McLuhan's "hot" to "cool" media through Post Malone's White Iverson. It highlights how SoundCloud democratized music and fostered interactive, participatory engagement.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"In the midst of global warming, an Alt-Right conservative uprising, a school shooting epidemic, and off the heels of the 2008 market crash came a nihilistic rap subgenre most commonly referred to as “Soundcloud Rap.” (Soundcloud Rap – Subcultures and Sociology, 2016). This new subgenre of hip-hop contains within its name a reference to the music-sharing platform SoundCloud, which gained immense popularity in late 2014 due to its opportunities for artists to upload and share their music freely. "These SoundCoud artists took control of their own destinies, releasing their own music on SoundCloud, succeeding at a pace that the traditional music industry couldn’t keep up with." (Pierre, 2019).

Although SoundCloud, and the sub-genre it created, are widely recognized, most research either focuses on the platform itself or on the hip-hop genre it , with almost no research focusing on both phenomena at once. Also, SoundCloud changed the way individuals interact with and listen to music on a worldwide scale, it influenced the 'global music interaction'.

The lack of research on this side of the coin, makes me want to narrow down the scope towards this aspect. With this paper, I want to answer the following question: how did global music interaction shift from McLuhan’s “hot” to “cool” media and how was this shift facilitated through SoundCloud? To properly analyze this, I am going to utilize Post Malone's “White Iverson” as an example of this shift.

Back to topHow did global music interaction shift from McLuhan’s “Hot” to “Cool” media and how was this shift facilitated through SoundCloud?

Verse 1: SoundCloud’s Primary Allure

Throughout the last 10 years, immense hit songs Sunflower, Rockstar and Congratulations have roamed the charts for weeks. The mastermind behind them is 28-year-old American Singer Austin “Richard” Post, better known as "Post Malone". Before selling out tours, transferring millions of records across the counter and becoming (one of) the most-streamed artists of the 2010s, Post uploaded his music to the free-streaming-and-upload service SoundCloud.

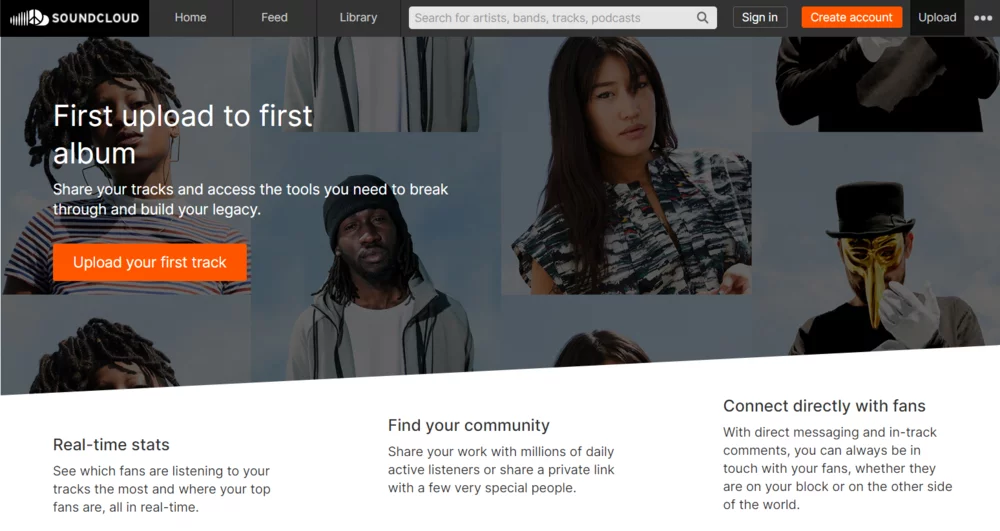

Founded in Stockholm by Alexander Ljung and Eric Wahlforss in 2007, "SoundCloud's original ambitions were relatively humble: It was built just to help music industry types share recordings with each other" (Van Buskirk, 2009). In 2009, the platform "secured an investment of €2.5 million from Doughty Hanson Technology Ventures in its first round of venture capital funding" (SoundCloud Closes €2.5M Financing Round, n.d.), . By 2009, “the website was challenging MySpace as the dominant online music-sharing platform, and by 2011 it had ten million registered users” (Hubbles et al. 2017), growing to “175 million monthly listeners by 2014” (Hubbles et al. 2017). Currently, "the service has more than 76 million active monthly users" (Smith, 2021) and individuals can interact with "over 200 million audio tracks" (Deahl, 2019). Everyone can build on this growing number of audio tracks as "egistration for accounts is free, and up to three hours of audio may be uploaded with a free account" (Hubbles et al, 2017).

The biggest song that emerged from SoundCloud is Post Malone’s break-out hit White Iverson. With over 400 million streams on SoundCloud alone, the record marked “the first time an artist could achieve immense musical recognition through a free online streaming platform on the internet.” (Chivetta, 2017).

On February 4th 2015, “White Iverson” was uploaded on SoundCloud and it grew massive, “earning over one million plays in just one month” (Lochrie, 2021). The song is the definition of “SoundCloud Rap” with “a proclivity towards (…) nonsensical repetition over substantial lyrical content” (Scheinberg, 2017) in combination with “septum-pierced (…) melodic, sing-raps” (Scheinberg, 2017). The song's sound deviated from prevailing trends in the hip-hop landscape, thus introducing a distinctive shift from mainstream conventions.

“SoundCloud social interactive features” (Hubbles et al, 2017). As can be seen in the highlighted areas in figure 1, the streaming service invites users to listen, comment, like, repost and share tracks, "fostering an online community through its inclusion of features (…) more commonly seen on social media” (Verespy, 2022). “Users have the ability to comment on them <tracks> and easily share them to their own feeds" (Rindner 2021). These features allow users to actively participate in the circulation of music audio as users can actively share, repost, like and comment on the tracks. White Iverson entrenched what distinguishes SoundCloud from other streaming platforms: its accessibility and social interactive features.

White Iverson entrenched what distinguishes SoundCloud from other streaming platforms: its accessibility and social interactive features.

Verse 2: Hot N’ Cool Media

Before diving into the global shift in music interaction, it is important to first define two concepts that allow us to understand the shift more in-depth. In his 1964 work Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man McLuhan makes a distinction between "Hot Media" & "Cool Media". According to McLuhan, “hot media is that which engages one sense completely. It demands little interaction from the user because it ‘spoon-feeds’ the content. Typically the content of hot media is restricted to what the source offers at that specific time.” (Hot Versus Cool Media - Media Technology and Culture Change, n.d.). “Hot media are (…) low in participation by an audience” (McLuhan, 1964, p. 32) Contrary, “cool media” is defined as “low-definition media that engages several senses less completely in that it demands a great deal of interaction on the part of the audience. Audiences then participate more because they are required to perceive the gaps in the content themselves. The user must be familiar with genre conventions to fully understand the medium"(Hot Versus Cool Media - Media Technology and Culture Change, n.d.).

Although these concepts were established decades before SoundCloud became a prominent force, they can be adapted as a theoretical framework towards the musical landscape. Before SoundCloud, the music industry and its major labels , from selection to promotion to distribution. This control influenced the musicthat was made available to consumers on formats such as cassettes, vinyl records or CDs. In this context,formats such as cassettes, vinyl records and CDs can be established as "hot media".. Here, the audience plays a passive role, . The audience only engages the sense of hearing completely, by merely listening to the music.

In contrast, SoundCloud is reminiscent of “cool media”. It where the e participation, interaction and utilization of multiple senses. Users can engage with audio tracks through comments, likes and shares, which fosters a dynamic and participatory environment. This also environmentencourages a higher level of engagement, as both creators and consumers play important roles in shaping the platform's content. In the following section, I will analyse the associated shift from “hot” to “cool” media, that is foregrounded by the success of White Iverson on SoundCloud.

Back to topVerse 3: Music Labels as Tyrians

"Youth is largely a period of self-discovery with a part of that process being rebellion against the accepted norms of society" (Verespy, 2023). Every generation has its own “subversive youth culture on the fringes of the mainstream that exists to provide access to a rebellious ethos" (Roy 2019) and in the 2010s that rebellious ethos was exhilarated through a sub-genre called 'SoundCloud Rap'. Originally, hip-hop/rap music was “a reaction to the socio-economic conditions in Black and Brown neighbourhoods” (Sharpe, 2023). With the intonation becoming increasingly popular, music labels realized that they could capitalize on the genre.

By the early 2010s, rap had fully emerged into mainstream American culture. However, because. ofthis development, major record labels felt the need to move “towards artists with less controversial public personas” (Verespy, 2022). During this time, profits in the music industry were going down “due to the decreasing popularity and lack of physical media” (Verespy, 2022), and streaming had not yet emerged as a serious alternative to the material formats that had previously satisfied the profit-driven music industry. Because of this, “major labels were unwilling to take risks on unproven up-and-coming artists” (Verespy, 2022). In this situation, the role of music labels was essential for the promotion of their artists, and consequently also to the development of their music. "The major record labels were able to use their oligopoly position and exclusive access to means of distribution, production and marketing to control the industry reaping the majority of the benefits" (Aspray, 2008).

Back to top"Youth is largely a period of self-discovery with a part of that process being rebellion against the accepted norms of society" (Verespy, 2023)

Verse 4: “Hot Media”

As mentioned before, albums, singles, vinyls and other music formats were historically used as "hot media". For these types of formats, music labels played a significant role by providing essential resources, such as recording studios. This support, however, often came with a trade-off. Music labels regularly limited the creative freedom of artists and exerted control over distribution, production and marketing processes. By doing so, major labels at least partially decided which music was widely distributed to the public, restricting what “the source offers at that specific time” (McLuhan, 1964), and creating a passive audience. This restrictive situation of low participation caused — combined with technological developments — pushed individuals to congregate on the only place available that would allow them to let their voices, and music, be heard: SoundCloud.

Back to topVerse 5: The Fertile Grounds of SoundCloud

The uploading of White Iverson to SoundCloud in February 2015 marked the first time “artists could achieve label attention or other musical recognition through a free online streaming platform on the internet” (Chivetta, 2017). Instead of relying on music labels, artists could gain visibility through the social and interactive nature of platforms while encoding their music with their the aesthetic choices, creating “a new avenue for music discovery, allowing artists to reach global audiences rapidly and organically" (Oliver, 2023).

Instead of artists desperately trying to reach record labels for notoriety, the popularity of White Iverson induced labels to prioritize reaching out to artists who were gaining attraction via online streaming platforms. Here, an adversative shift emerged that battles with the commercialised music industry which valued capital over creative exploration. At the heart of SoundCloud’s appeal was the fact it allowed "musicians (...) to <freely> upload their own content onto the platform without the need of a record label" (TwelveRays, 2021), which caused "listeners options to be not limited by the gatekeepers of the music industry, namely major labels" (Soundcloud Rap – Subcultures and Sociology, 2016). The success of songs like White Iverson exposed and questioned "power dynamics that favor parties entrenched in traditional industry roles" (Dunham, 2021, p. 2) and introduced a new model where creative exploration was deemed a priority, with capital being the second priority.

Although SoundCloud provided a unique opportunity for individuals to upload their music and potentially go viral, not everyone who utilized the platform achieved acclaim. The democratization of the platform also meant a flooded market with an abundance of individuals vying for attention. The sheer amount of content available on the platform made it challenging for artists to garner the attention necessary to achieve broader success. However, though not every SoundCloud artist became a sensation, the platform's democratized nature allowed a multitude of new voices to be heard.

Back to topVerse 6: "Cool Media"

As established, the platform’s popularity can be traced back to accessibility. According to McLuhan, the audiences of cool media participate more actively “because they are required to perceive the gaps in the content themselves” (McLuhan, 1964). SoundCloud allows everyone with an account to make, upload and share their music, allowing for “high participation by the audience” (McLuhan, 1964). There is an absence of stringent entry requirements. In this sense, SoundCloud lowers the entry barrier and offers an opportunity for audiences to participate in content creation themselves.

McLuhan’s idea of perceiving gaps in the content of “cool media” also suggests that audiences actively fill and contribute to aspects of the content themselves. This contributing ability has led to the introduction of unconventional genres and styles of (rap) music, such as Post Malone’s work is a good example.

To fully grasp and engage with this diverse and diverging content, users must be familiar with a broader range of genre conventions than those typically presented in the controlled environment of "hot media"; an action that demands more social interaction. SoundCloud provided new opportunities for this type of interaction through its affordances that encourage multisensory engagement.

Instead of merely listening to the music, the platform encourages users to participate socially — e.g. through commenting, liking and sharing —, which fosters a sense of community and dialogue. It is through this social interaction such as commenting and sharing that we can evaluate SoundCloud as a "cool media". This social interaction, however, not only fosters a sense of community, but also initiates a dialogue surrounding the music where individuals can become familar with the broader range of genre conventions and perceive the gaps in the content themselves. These multisensory user engagements and multifaceted interactions exist in contrast to the more predefined, uniformed nature of the music landscape, breaking away from the passive consumption associated with “hot media”.

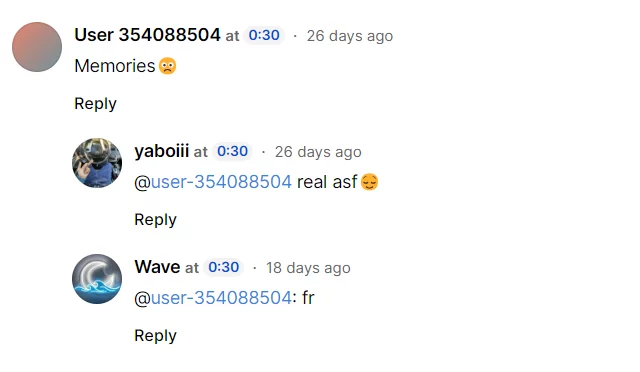

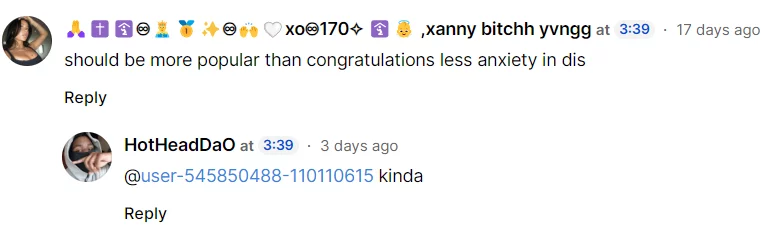

As illustrated in figures 3 and 4, users continue to actively engage with White Iverson, even eight years after its original release. This ongoing interaction exemplifies the essence of "cool media" and underscores its significance in transforming how audiences connect with and contribute to music content.

Chorus: Becoming One’s own Tyran

Even if the SoundCloud gold rush has subsided, "new musical movements will continue to originate and thrive on SoundCloud, because of the unique ways artists can directly connect with a community around their sound and expression” (Rindner, 2021). Its low entry barrier and emphasis on social interactions allowed for diffraction from other streaming platforms but primarily empowered some artists to transition from obscurity to recognition.

Individuals no longer passively consume music through cassettes, CDs or vinyls dictated by major labels. Instead, they actively participate in shaping the meaning of popular music through social interactions. This shift from passive consumption to active interaction signifies a transformative journey from the restrictive nature of “hot” to the participatory realm of “cool” media, with SoundCloud playing a pivotal role in reshaping and democratizing the dynamics of online music distribution and interaction.

While physical spaces remain crucial in the music industry’s prominence, White Iverson’s legacy underscores the rise of thriving music communities and genres within digital spaces. Although not everyone who made a SoundCloud account became achieved musical acclaim, the platform's break away from the corporate dominance of (digital) capitalism revived the true essence of hip-hop music: providing marginalized communities with a voice.

Currently, SoundCloud is financially struggling as in August 2022, "the company announced that it was cutting approximately 20% of its workforce due, in part, to recent changes in the global economic landscape" (SeventhQueen, 2022). While the initial wave of 'SoundCloud Rap' and its cultural impact remains undeniable, questions about the platform's ability to sustain its unique position in the musical landscape are relevant. The fact remains that the apparent transition from “hot” to “cool” media as signified by SoundCloud afforded individuals the opportunity to assume greater control over their creative endeavours, allowing them to become ts.

Back to topReferences:

Aspray, William, ed. (2008). “File Sharing and the Music Industry.” In The Internet and American business, ed. William Aspray and Paul E. Ceruzzi, 451-91. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press. Retrieved from: https://www.scribd.com/doc/215055425/Aspray-Ceruzzi-2008-The-Internet-and-American-Business

Breakout Artist: Rising Stars: Exploring the journey of breakout artists - FasterCapital. (z.d.). FasterCapital. Retrieved from: https://fastercapital.com/content/Breakout-artist--Rising-Stars--Exploring-the-Journey-of-Breakout-Artists.html

Caramanica, J. (2017). "The Rowdy World Of Rap’s New Underground." New York Times (Online) Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/22/arts/music/soundcloud-rap-lil-pump-smokepurrp-xxxtentacion.html

CalypsoRoom Editorial Team. (2023, 29 augustus). "The impact of music social networks on artist-fan interaction." CalypsoRoom. Retrieved from: https://www.calypsoroom.com/music-social-networks-impact-artist-fan-interaction.html

Ciavatta, R. (2017, 6 oktober). "SoundCloud’s story".Medium. Retrieved from: https://medium.com/@ciavatta/soundclouds-story-ea092f8ca996

Deahl, D. (2019, February 13). Over 200 million tracks have been uploaded to SoundCloud. The Verge. Retrieved from: https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/13/18223596/soundcloud-tracks-uploaded-200-million

Dunham, I. (2022). "SoundCloud Rap: An investigation of community and consumption models of internet practices." Critical Studies in Media Communication, 39(2), 107-126. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/15295036.2021.2015537?needAccess=true

Grove, R. (2022, December 9th). "‘Stoney’: How post Malone forged his musical identity." uDiscover Music. Retrieved from: https://www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/post-malone-stoney-album/

Hot versus cool Media - Media technology and culture change. (n.d.-b). https://mediawiki.middlebury.edu/MIDDMedia/Hot_versus_cool_media

Hubbles, C., McDonald, D. W., & Lee, J. H. (2017)." F#%@ that noise: SoundCloud as (A-)social media?" Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 54(1), 179–188. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2017.14505401020

Lochrie, C., (2021, August 29th). "Five of the biggest and best SoundCloud success stories." Tone Deaf. https://tonedeaf.thebrag.com/five-of-the-biggest-and-best-soundcloud-success-stories/list/post-malone/

Mackin, A. (2021, September 10th) "Before Soundcloud. Cultural History of the Internet." Retrieved from: https://culturalhistoryoftheinternet.com/2021/09/09/before-soundcloud/

McLuhan, M. (1964). “Understanding Media: The Extensions Of Man”. https://designopendata.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/understanding-media-mcluhan.pdf

Phillips, M. T. (2021). "Soundcloud rap and Alien Creativity: Transforming Rap and Popular Music through Mumble Rap." Journal of Popular Music Studies, 33(3), 125–144. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1525/jpms.2021.33.3.125

Pierre, A. (2019, February 27th). How rap’s SoundCloud generation changed the music business forever. Pitchfork. Retrieved from: https://pitchfork.com/thepitch/how-raps-soundcloud-generation-changed-the-music-business-forever/

Rindner, G. (2021, December 16th). "The History of SoundCloud Rap, a Face-Tatted vision of hip-hop’s future." The Ringer. Retrieved from: https://www.theringer.com/2021/12/16/22838951/juice-wrld-soundcloud-rap-history-retrospective

Roy, M. (2019.) “Soundcloud rap: what is rap’s latest genre?” YA Hotline. Retrieved from https://ojs.library.dal.ca/YAHS/article/view/9483

Scheinberg, M. (2017, October 10th). "Understanding Soundcloud Rap." LNWY. Retrieved from https://lnwy.co/read/meet-soundcloud-rap-hip-hops-most-punk-moment-yet/

SeventhQueen. (2022b, August 25). How SoundCloud Changed Music. Recording Arts Canada. Retrieved from: https://recordingarts.com/how-soundcloud-changed-music/

Sharpe, M. (2023, 19 januari). "What is hip-hop and why does it matter?" Academy of Music and Sound. Retrieved from: https://www.academyofmusic.ac.uk/what-is-hip-hop-and-why-does-it-matter/#:~:text=Hip%2Dhop%20emerged%20in%20part,part%20of%20hip%2Dhop%20culture.

Smith, C. (2023, January 8). SoundCloud. DMR. Retrieved from: https://expandedramblings.com/index.php/soundcloud-statistics/

SoundCloud closes €2.5M financing round. (n.d.-b). Science|Business. https://sciencebusiness.net/news/69432/SoundCloud-closes-%26euro%3B2.5M-financing-round

Soundcloud Rap – Subcultures and Sociology. (2016, 16 July). https://haenfler.sites.grinnell.edu/subcultures-and-scenes/music-cultures/soundcloud-rap/

Van Buskirk, E. (2009, July 6). SoundCloud threatens MySpace as music destination for Twitter Era. WIRED. Retrieved from: https://www.wired.com/2009/07/soundcloud-threatens-myspace-as-music-destination-for-twitter-era/

Verespy, O. (2022, December 5th). "The what, how, and why of SoundCloud rap". ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved from: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/f92afacc60fd4b78972c0ffd11c8761e

Twelverays. (2021, May 17th). "How digital marketing is influencing music." Twelverays. https://twelverays.agency/blog/how-digital-marketing-is-influencing-the-...

Oliver, P. G. (2023, 29 mei). "TikTok’s impact on the music industry - inside the music industry." Medium. Retrieved from: https://medium.com/inside-the-music-industry/tiktoks-impact-on-the-music-industry-17a5fa105da

Back to top