Singing along to Electric Callboy in text-based live chats: a neotribal practice

Singing along to music has been an age-old practice, yet how does that work when our interaction gets more digitalized? In this study, singing along to music has been looked at through Maffesoli’s concept of neotribalism. Three YouTube Premieres from the band Electric Callboy form the basis to look deeper into how their fans create a sense of community when neotribal practices enter the technoscape. To fulfill their communal needs, fans typed lyrical items into the live chat, thus giving a new dimension to singing along to music.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Singing along in the online space

The online world has shaped our social interaction as a whole. Therefore, to understand group interaction and identity features of online users, Blommaert advocated taking an action-centred approach (2019a:112-113). This approach means that sociolinguistic research on online interaction says little about the participants involved in the social action, but the action itself can be investigated and can serve as a firm empirical basis for theory construction. In another paper, Blommaert (2019b:486) argued that researching online interaction leads to investigating seemingly small things, because the moment of interaction is taken as a base and from there on the larger identity practices of the social group can be better understood. Such small moments of interaction are not meaningless, but they demonstrate powerful ordering effects in communities and collective identities, suggesting that communities display power to regularise certain behaviour.

Hence, this study focuses on the collective interaction of singing along to music. As argued by Blommaert (2019a), online and offline practices cannot be separated in our current sociolinguistic context, therefore, the act of singing along will be looked at on the online platform YouTube, specifically in the video premiere format. First, some theoretical foundations will explain how social groups can be understood through a neotribal lens; how singing along fits the concept of neotribalism; and how the technoscape and sociability are connected. Then, small instances of the singing-along interaction will be presented and linked to neotribalism.

Back to topThe neotribal group

The concept of neotribalism comes from Michel Maffesoli (1996), where it is argued that a group, in subcultural theory, should be seen as a tribe. This means that the group does not have rigid forms of organisation, but is flexible in its expression, as the group favors appearance and form above rigid organisation (Bennett, 1999:605). Bennett (1999:606) also argues that the concept of seeing social groups through the lens of tribalisation illustrates the temporal nature of collective identities in modern consumer society, because individuals continually move between different sites of collective expression in which they have to (re)construct themselves accordingly. The idea of mutually adjusted personas reflects the individualised form of socialisation typical of the modern age. The social centrality draws individuals together, so that the tribelike temporary group condenses out of the homogeneity of the mass.

This newly developed mass should be seen as a liberation rather than an oppression of individuals, as the individuals in the tribe can express themselves through a range of commodities and resources (Bennett, 1999:608). Maffesoli (2021:217) added that neotribalism is a specific form of collectivity, yet it represents all the traditional aspects of socialisation in which individuals become part of a group and therefore transcend the individual. What is different is that the collective sensation and actual participation are more important than normative coercion or a common rational project. The result of neotribal practices and traditional socialisation is the same, because individuals become part of the social body, thus losing themselves in a collective subject (Maffesoli, 2021:217-218).

Back to topSinging along as a neotribal practice

Pawley and Müllensiefen (2012:141) state that people can form such neotribes by uniting themselves in singing along to live music. When people engage in music, they express their pleasure and excitement in partying while also demonstrating their desire to partake in the partying to other members of the tribe. The authors further argue that audiences singing along can experience a social bond with others and feel connected to the performers by engaging with live music and therefore a new social reality can be constructed for the duration of the event, whether it is a festival, a concert, a pub or a nightclub (Pawley & Müllensiefen, 2012:131).

When audience members sing along, they affirm the neotribal relationship they have with the artist and each other. One of the clearest moments in which audience members pick up the lyrics is during choruses, because the words become detached from the semantic significance and the audience simply engages in a lyrical narrative (Negus, 2007:78-79). In some cases, the sung words do not represent the full or correct lyrics, but the social bonding practice remains.

Finally, Werner (2023:10) added that pop songs are filled with non-lexical music tropes, called vocables, which carry no semantic meaning but are used repetitively for vocalisation. These vocables are present for aesthetic reasons, yet they are part of the lyrical compendium.

Back to topNeotribalism in the technoscape

Today, much of people’s social interaction happens online and is,therefore, mediated through some sort of social media platform. Robards (2018:202) states that contemporary social media platforms follow a neotribal bonding concept. For this reason, social media can be mapped out as a set of neotribes, especially because each specific social media platform covers the full gamut of human interests, experiences, and practices. Therefore, the reality is not one neotribe per platform but all neotribes across all platforms.

Interestingly, these platforms have increasingly stepped away from primarily textual mediums and instead have taken a visual turn, which shapes how our sociality plays out online (Hart, 2018:207) Yet not all platforms discard the textual medium as a communication mode, as every platform enables or constrains specific actions of its users through affordances (Ronzhyn, Cardenal & Batlle Rubio, 2023:3175). Such technological affordances create a context in which the potential actions of the users are shaped (Ronzhyn et al., 2023:3177). In other words, platforms with high textual affordances shape their users to interact more through text. Twitter and Facebook have been the main subject of affordance investigation, while the social aspects of a platform like YouTube have been relatively understudied (Ronzhyn et al., 2023:3171-3172). Also, with live streams on the rise, Coats (2024:16-17) argues that it is important to look deeper into people's interaction on live stream chats, because thesechats often seem fast-paced and lack interactional coherence. In the scope of singing along as a community experience, it is worthwhile to investigate whether the textual affordances of live stream chats would form a barrier to the vocal practice affiliated with singing.

Back to topResearch scope

The aim of this study is to find out how the neotribal practice of singing along to live music translates to the technoscape. Specifically, when neotribal practices happen during broadcasted premiering videos in which people have to deploy textual modes of communication, rather than singing in the traditional vocal sense, because of the enabled and restricted affordances of YouTube’s Premiere live chat.

Data collection

I started digital fieldwork in September 2024 for five weeks. At first, I looked at pop music in the broadest sense (encompassing all genres from EDM to metal) and glanced at the live chat replays. From this, the eclectic metal band Electrical Callboy became the main focus, because their new album has consistently been premiering on YouTube with the live chat enabled. From the bands I glanced at, Electric Callboy showed a rigorous consistency in engaging the audience through these premieres.

Electric Callboy is a German band combining metal with electro music. They started in 2010 (under a different name) and announced a new singer in 2020. Their fanbase has strong foundations in creating an active community, which, like Keunen (2002:137) argued, is to be expected in metal music.

Data analysis

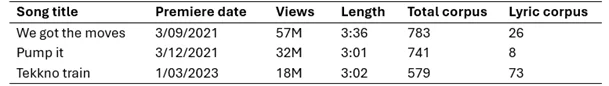

To narrow the scope of the analysis, only YouTube premieres from after the introduction of their new singer (Nico Sallach) were chosen, because the audience had to get acquainted with Sallach's style and performance. Also, video clips featuring other artists were dropped from the data collection, as I really wanted to look into the behaviour of Electric Callboy’s fan base. Finally, I set a threshold of at least 15 million views to ensure I analysed the most popular premieres. Table 1 shows a full overview of the selected data information. It is important to note that concerning the corpus of the live chat, I kept the default option of ‘top chat replay’ because that is what the default audience would see during the premiere. Furthermore, I only counted an item as a sing-along lyric if the text actually mimicked the lyrics. Finally, I will discuss three specific non-lyrical comments concerning the neotribal theory.

Singing in the live stream chats

Chorus

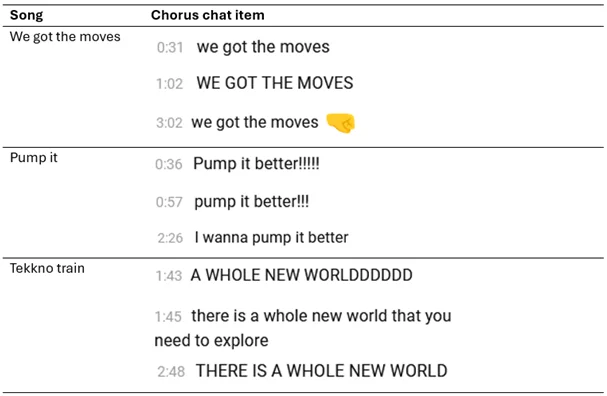

Table 2 shows three chorus-related chat items for each song. In We got the moves, it is clear that the audience reproduces only the main phrase; the song title. It was very typical to see the item written in caps or affixed with an emoji. The chat of Pump it demonstrates that exclamation marks could also accompany many lyrical items. Furthermore, they show that the most emphasised part of the phrase can stand alone as a sing-along piece and that it is unnecessary to communicate the whole phrase, as seen in the third example. Finally, the live chat of Tekkno train displays three different instances of how smaller bits of a chorus phrase can be used as a complete practice of singing along. Bits and pieces can be dropped or added by the audience members themselves, while still fully participating in the neotribal practice.

Vocables

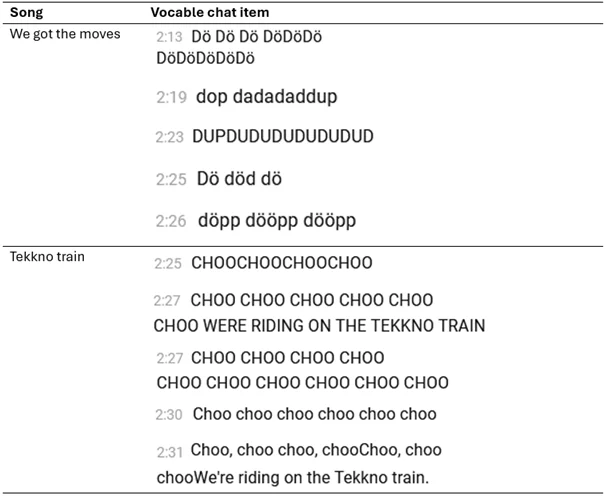

Table 3 shows that vocables play a major role in singing along. Pump it does not have any vocables and is therefore not included, showing that - even though vocables are important - they are not necessary for singing along. The lack of vocablesexplains why the lyric corpus of Pump it is so small compared to the other songs. The vast majority of the lyric corpus in the two other songs is there because of the vocables. From both songs, five examples are given. In We got the moves, it is seen that many of the audience members write the vocables in the German orthography. Yet some other variations appear, which can indicate that not all audience members are German. Other chat items demonstrate that an international crowd is present. The examples in Tekkno train show that other lyrical items can accompany vocables. In two of these examples, the vocables are extended by a follow-up lyric.

Unique items

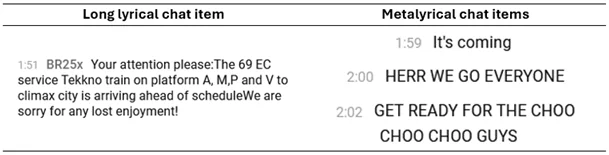

The Tekkno Train chat revealed several unique items, displayed in Table 4. The first item is a long lyric that was repeatedly posted by the same user five times, even though this lyric only occurs once in the whole song. This chat item contained the full spoken text by a supporting vocalist before the song’s breakdown (a musical part characterised by heavy guitar drones). This lyric was placed in the chat a bit before it was uttered in the video clip. This means that the user was already aware of the lyrics before the video premiere, perhaps from a live show or an earlier posted instance of the song.

The other three items in Table 4 are not lyrics, but are about the lyrics to come. It shows that some lyrics are indeed anticipated somehow, as they all refer to the upcoming vocables. The users are communicating with their peers that vocables will come soon, and they try to catalyse the neotribal singing along practice with it. These items can be seen as metalyrical communication in which users encourage their peers to sing along.

The interactional coherence of the online neotribal community

Coats (2024) argued that live streams often seem fast-paced without interactional coherence. Therefore, they would be an interesting topic of study to find out how online communities actually behave. Investigating the live chats during three Electric Callboy YouTube Premieres revealed some interactional coherence through the lens of singing along. Both the neotribal conceptualisation and the platform affordances shape the way in which users can form such interactional coherences.

The interaction that took place in these live chats was solely text-mediated (Ronzhyn et al., 2023), yet this affordance was no restriction for the users to find a way to sing along. The results show that the audience members could express their pleasure and excitement in partying by typing parts of the choruses and vocables in the live chats (Pawley & Müllensiefen, 2012). Negus (2007) mentioned that choruses form a crucial part in the neotribal practice of singing along, which was confirmed in all three premieres. Yet, the importance of vocables as a catalyst had an even greater effect on the audience (Werner, 2023), as both premieres containing vocables displayed a much larger singing-along corpus.

Furthermore, the metalyrical items showed that audience members demonstrate their desire to partake in the partying to other members of the tribe in a similar way as it would happen offline (Pawley & Müllensiefen, 2012). The text-based chat did not restrict the audience in expressing these desires, and so the neotribal practice of singing along translates to the technoscape. This shows that people do not need to be in the same music club or festival ground in order to catalyse the party sensation. Instead, they can be connected as a neotribe through a digital medium such as a live chat.

To conclude, these live chats show that the audience has a very flexible expression through a range of commodities and resources in which a tribelike group condenses out of the mass, which in turn reflects the individualised form of socialisation (Bennett, 1999). The chorus and vocable-related chat items varied among the audience members in many ways, yet they also formed a homogeneity in which the individuals became part of a group and, therefore, transcended the individual (Maffesoli, 2021). Thus, the text-based platform affordances did not seem to form a barrier against the neotribal importance of collective sensation and actual participation in singing along.

Back to topReferences

Bennett, A. (1999). Subcultures or neo-tribes? Rethinking the relationship between youth, style and musical taste. Sociology, 33(3), 599-617.

Blommaert, J. (2019a). Formatting online actions: #justsaying on Twitter. International Journal of Multilingualism, 16(2), 112-126.

Blommaert, J. (2019b). From groups to actions and back in online-offline sociolinguistics. Multilingua, 38(4), 485-493.

Coats, S. (2024). A Framework for Analysis of Speech and Chat Content in YouTube and Twitch Streams. In Proceedings of the 11th Conference on Computer-Mediated Communication and Social Media Corpora for the Humanities. Université Côte d’Azur, 2024.

Hart, M. (2018). #Topless Tuesdays and #Wet Wednesdays: Digitally Mediated Neo-Tribalism and NSFW Selfies on Tumblr. In Neo-tribes: Consumption, Leisure and Tourism. Chapter 13, 207-219.

Keunen, G. (2002). Pop! Een halve eeuw beweging. Lannoo.

Maffesoli, M. (1996). The Time of the Tribes: The Decline of Individualism in Mass Society. SAGE Publications, Limited.

Maffesoli, M. (2021). Collective narcissism: some basics of neo-tribal sociality. In Youth Collectivities, Routledge. 215-221.

Negus, K. (2007). Living, Breathing Songs: Singing Along with Bob Dylan. Oral Tradition, 22(1), 71-83.

Pawley, A., & Müllensiefen, D. (2012). The Science of Singing Along: A Quantitative Field Study on Sing-along Behavior in the North of England. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 30(2), 129-146.

Robards, B. (2018). Belonging and Neo-tribalism on Social Media Site Reddit. In Neo-tribes: Consumption, Leisure and Tourism. Chapter 12, 187- 206.

Ronzhyn, A., Cardenal, A. S., & Batlle Rubio, A. (2023). Defining affordances in social media research: A literature review. New Media & Society, 25(11), 3165-3188.

Werner, V. (2023). English and German pop song lyrics: Towards a contrastive textology. Journal for Language Technology and Computational Linguistics, 36(1), 1–20.

Back to top