Good Job, +15 Points: How the internet makes sense of China’s Social Credit Score system

This paper dives into the analysis of the use and implications of Internet memes based on China's Social Credit Score System (SoCS) on the premise of constructing a common ground between Western and Eastern online communities.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

From an Orwellian-like surveillance system to every comedian’s throwaway joke, how China’s SoCS policy is condensed into a popular internet meme is interesting. Even when you haven’t heard about the actual policy, you’ve probably seen netizens with their ‘scores’ deducted, as they share their hot takes on China and Taiwan. Becoming more and more tongue-in-cheek in dialogues, it is certainly “a shared social phenomenon” (Shifman, 2013, p.365). In fact, Shifman’s framework can approach them scientifically. Consisted of content (the ideas and ideologies conveyed), forms (ways we perceive them) and stance (how we can position ourselves and participate in them) (p.367),

we in this articlethese memes underliningdeliver meanings beyond the Chinese policy and become an ‘aesthetic’ to work across mediums.

Originally intended for Chinese viewers, viral Mandarin social media videos, such as actor John Cena's Mandarin apology video and other eye-catching Chinese TikToks are among the common remix subjects. With both their faces and Mandarin misunderstood and reinterpreted in another context, this forms another type of aesthetics. To Goriunova (2014), memes’ aesthetics stems from a “multi-layered individuation” (p.62), like a theatre unfolding lasting ideas. As “loaded forms” (p.65) under specific cultural and historical contexts, they reflect collective concerns to the status quo, plus its effect on the author with “conceptual personae” (p.66) at play. The exoticism to a foreign language and race may contribute to the memes' rise.

Furthermore, China’s sensitiveness in simply mentioning Taiwan or the June 4th Incident are often mocked, which is seriously refuted by Zhouwith official doctrines and linked the emotions to techno-Orientalism: P. Her analysis was panned on Twitter, as commentators prioritized the memes’ ‘silliness’ over accuracy.

With Berger’s emphasis on word of mouth in viewers’ affection (2014), I’d argue they build up a political collectivity aside from the laughs. As their emotions are aroused, people garner more sharing to communicate their desired identities (p.591), then infer a more engaging experience, cope with and make sense of challenging situations, or be part of a group. The memes’ repeated political arguments and the group they form are to be explored. analyzed

we will be mainly samplingconsisted

Back to topChina's Social Credit Score as context

China’s SoCS scheme debuted in 2014 as an expansion to the existing system for business, and was trialed in cities like Suzhou (Bloomberg News, 2019). There, citizens are ranked with a base score and are encouraged to work it up by making ‘right’ choices in daily lives or by doing good deeds. Reversely, not only will they lose their ability to fly and more if rankingit drops to unacceptable levels, but their names and mugshots will also be displayed for public shaming. These, plus restricting local petitions to higher authorities (shangfang) by automatically reducing their ranks, attracted criticism from the West for intruding individual privacy and freedom.

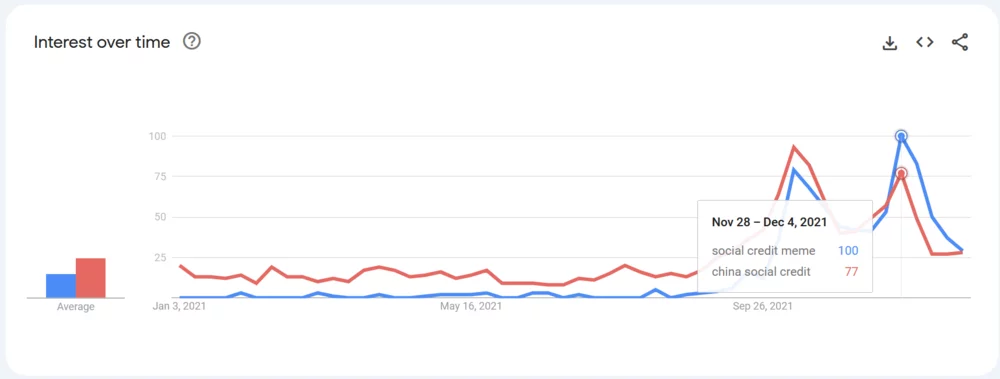

Despite its name, the SoCS meme’s origins weren’t from the Chinese scheme. Instead, its origins are more akin to wumao (50 cents) in the Chinese internet landscape: Commentators routinely posting pro-China troll comments for minimal monetary returns. In the Russian context, the meme started as a mockery to pro-China comments written in broken Russian on local forums. Their salaries for their ‘hard work’ – 15 Rubles per comment – is then highlighted in images circulating in 2021, which are sarcastically related to social credits rather than money. In the West, meanwhile, although it was used on Reddit earliest in April of that year, it wasn’t until late 2021 when various video remixes went viral on YouTube, which in turn pushed the query “social credit meme” to its highest per Google Trends.

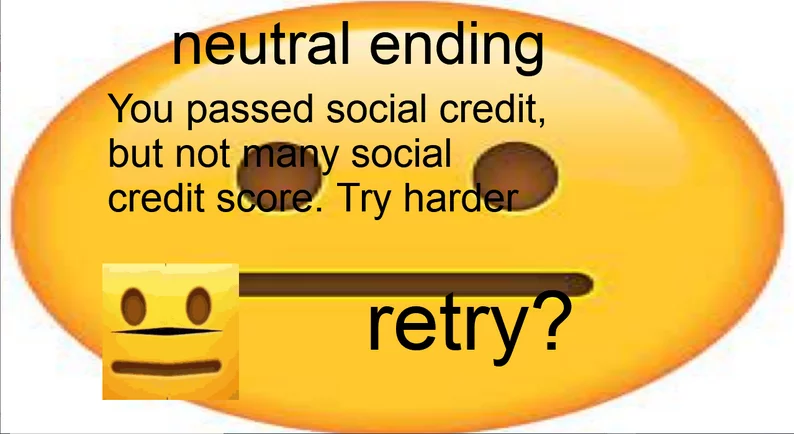

As one of the main arenas for the meme, this article will analyze discourses surrounding it on Reddit, where its sub-reddit mechanism flourishes groups specialized in creating memes and further remixes. Particularly, we’ll be mainly sampling posts from r/socialcreditmemes, a 2,000-member subreddit consisted of SoCS memes and creative spin-offs like a text-based game. Aside from this, representative posts are also selected from the query “social credit memes” and its major variant “John Xina” on r/memes, Reddit’s largest meme sub-reddit with nearly 25 million members, to see how they’re perceived in a more mainstream community.

Back to topRouting Out the Meme

Per Shiftman (2013), the spread of memes is a process of express diffusion, reproduced in various imitation means, and the adaptations they made in sustaining in the sociocultural environment (p.365). In clearing up the SoCS meme, its variants and imitation, we this article utilizes the “ability to trace the spread and evolution of memes” (ibid), and came up with the following graph. The events listed here can be categorized into three larger themes: The original memes’ context, the concurrent ‘Chinese’ memes, and Chinese current affairs, whose significance on evolving the meme would be discussed in detail.

The Original Social Credit Score Memes

To start, we need to look at the initial reaction images.

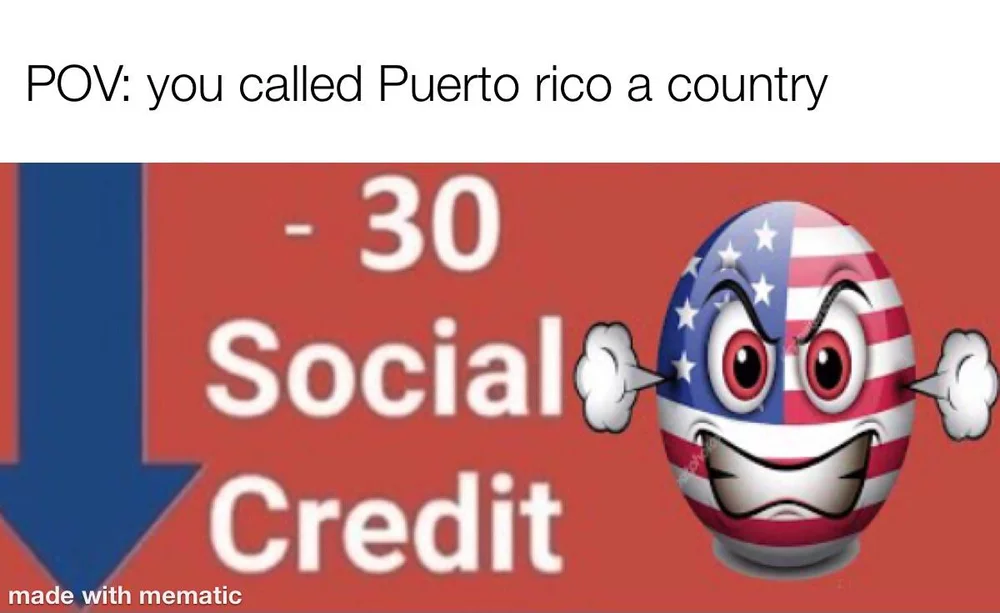

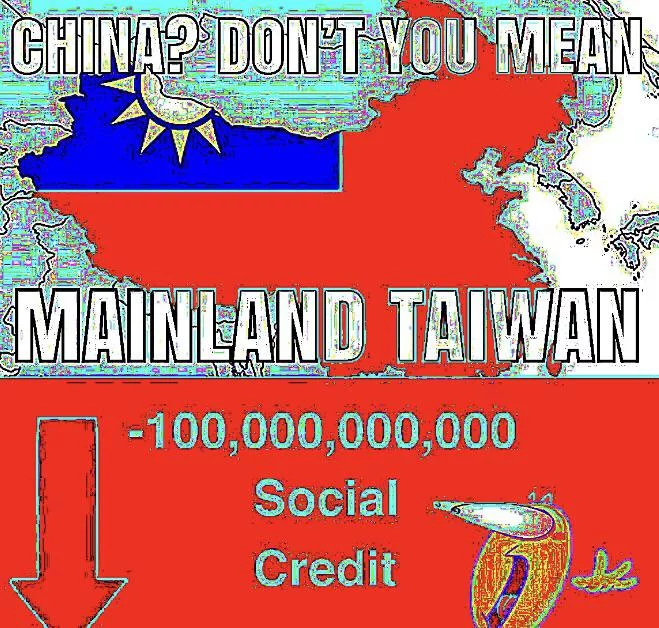

In terms of the content, the images mainly consist of other internet users judging the original poster’s speech under the fictional ‘social credits’. Having a direct opposite, it (dis)encourages one kind of behavior over the other – not recognizing Taiwan as a country or the June 4th Incident in the case of most SoCS memes. Meanwhile, in terms of stance, they suggest an overarching ‘system’ where we, plus the poster, are tracked constantly under.usour

These images, therefore, are akin to fine tickets issued to drivers, satirically keeping us at bay in expressing our opinions to prevent a 'fatal' score deduction.

With the editability of the images, however, we can also ‘watch’ others’ activities and hand these ‘tickets’ out as we (donon’t) like.

Much like Shifman’s analysis on the “Leave Briney Alone” meme (2013, p.370), the low-effort form is imitated on top of the original image, now with more apparent links to a country’s culture and history. Here, their composition remains the same, with the +/- [number] social credit and huge symbolizing arrows continue to be seen. The surveilling ‘credit’ system also stayed, but its ‘leader’ can be the head of a specific state, like seeing Chiang Kai-shek’s face in the Taiwanese variant. Being more nationally specific, nationalism can also be satirized. From the humanified ‘America’ emoji’s angry face, we can imply that ‘it’ sees the speaker as ‘not American’, as they see Puerto Rico, geographically part of the US but less so identity-wise, as a country.

In contrast to the surveillance system referenced, the memes’ low qualityin dent the possible techno-Orientalist vision, which resents the authoritarian China and reflects the fear of being closely monitored (Zhou, 2021). In the variations, only the latter meaning persists while the “referential” function (Shifman, 2013, p.367) – their underlying contexts – is easily changeable. Meanwhile, although Asian stereotypes can make technological advancements to be more ‘mythical’ (Roh et al, 2015, pp.14-15), the mishmash of arrows, Chinese and English characters around the ancient Chinese man emoji show the little effort paid in making the meme – a style then imitated in derivative custom games.

Back to topPresented in badly-recreated images, the SoCS system is less sophisticated and hastily done, but still eerie in principle.

Lost in Translation

Moreover, SoCS meme remixes can be a “social response” (Goriunova, 2014, p.58), through changing perceptions on celebrities like John Cena. Claiming Taiwan “the first country” to watch F9, the Chinese social media outrage forced him to apologize to secure the Chinese box office. Blasted in the West, the image of John Xina – combining Cena with Xi Jinping – was created (Carry, 2021). TAlas, the politcal critiques are slightly hampered in being remixed with the Bing Chiling [ice cream in Hanyu Pinyin] meme, another joke based on his Mandarin and exaggerated motions in promoting the film on Chinese Twitter counterpart, Weibo.

Using Cena's light-hearted internet image as the medium, the memes “work from within” (Goriunova, 2014, p.66), building an ‘enforcer’ or ‘loyalist’ image to both the SoCS meme system and Cena, who had been a popular figure on the internet for years. They're also externally intertwined with “larger assemblages of power, normativity, and history” (ibid, p.65). Here, not only is China-Taiwan relations parodied as a recurring topic, but Hollywood’s reliance on the Chinese market is also highlighted, as the original videos are made to promote the blockbuster in the nation, spoken with local audiences in mind. The Xena meme can hence be a collective resonantion against such inclination, in making fun of the language used and the faces who are willing to do so.

At the opposite side, Chinese viral videos are also the source for SoCS meme remixes, as a part of being subjected to both Chinese- and English-speaking online communities. A more well-known example is Super Idol, stemmng from a Putonghua pop song 热爱105°C的你 [Loving you at 105°C] on Chinese TikTok. Debuted in 2019, it wasn’t known before being reuploaded to YouTube 2 years later. Intended to sell bottled water to a Chinese audience (hence the 105°C in the title – the temperarture for distilled water), its lyrics were “incompatible” (Goriunova, 2014, p.59) to most of the internet. However, the actor's accompanying actions from the video, often characterized as an 'oily' way of flirting on the Chinese internet, opened a space between itself and part of existing meme formats (p.60). As it crossed over with SoCS memes, the intended heartwarming and positive message from the motions is appropriated like a means of aggression, "playing the network" (p.66) of SoCS memes as a violator to the existing ‘system’.

Though misinterpreting Putonghua in achieving the comedic effect in the memes, the Chinese online figures are at play with a larger network of meanings, instead of being excluded from it. Both the Super Idol and Cena’s Bing Chiling memes originated from Douyin, which is simultaneously rising with TikTok globally. With a lot of the content from the latter cross-posted to TikTok, Western users enjoy a large influx of content broadcast in a different language. As the eye-catching performances in these short videos are becoming “well-established discursive formations” (Goriunova, 2014, p.65) upon daily usage of the platform, they utilized the act and project fictional alter egos onto them, per their understanding of the Chinese society. Hence, we see Super Idol offending the SoCS instead of singing a love song, while Cena is dressed up in a Maoist outfit.

Back to topThe (n)everchanging politics

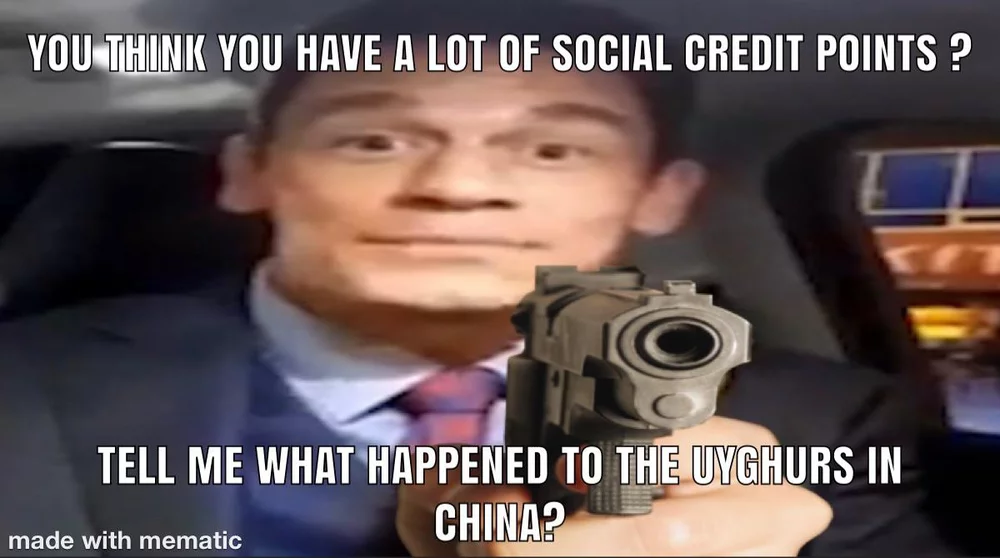

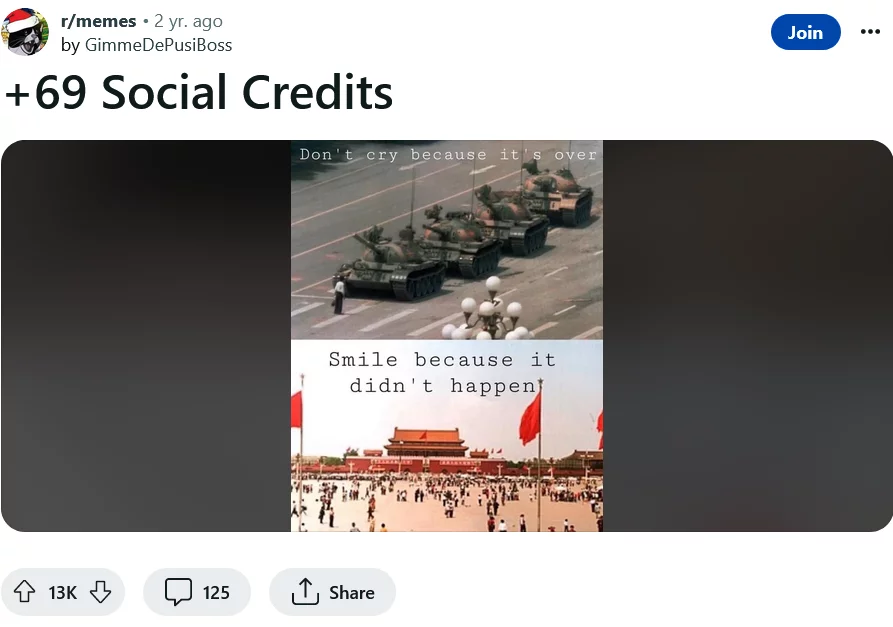

A recurring theme in SoCS memes is satirizing Chinese political censors, by mimicking deniers of Taiwan and the June 4th Incident. Like variants that play on national stereotypes, these convey a sense of belonging closer to official Chinese narratives. Adding their own twists in ‘confirming’ their ‘non-existence’, netizens respond to show they’re “in-the-know” (Berger, 2014, p.590) of the SoCS mechanism, enhancing their sense of belonging (and their fictional ‘scores’) in playing the common denial as the others. Yet, continuing such ‘theory’ can be confusing to some out of the loop, as seen in one that mistakes the actual movement and the censorship with movies in the 1989 meme, contrary to the “useful information” motive Berger suggested (Berger, 2014, p.590).

Compared to continuing discourses like Taiwan, individual events are less likely to be reproduced in SoCS memes, unless overlapped with other fandoms like sports and gaming. The former is best exemplified by then-Boston Celtics player Enes Kanter, a vocal critic against Chinese government’s oppression to Tibetans in October 2021.

As a hugely popular platform in discussing the NBA games, Kanter’s activism was shared and appreciated by Reddit users, and then remixed with preceding John Xina and SoCS memes. This can be seen as to grasp people’s “common ground” (Berger, 2014, p.595) on both the tournament and Kanter’s action, as well as raising an amused feeling with the exaggerated Cena posing in contrast to Kanter’s smugness.

Meanwhile, the latter shows how an issue is more seen abecamefter the meme’s rise. To curb tteenagers’ online addiction, the government restricted their time playing online games to 90 minutes per weekday in 2019. As China’s SoCS had been running by then, there’re memes linking the two. Despite posting on a large sub-reddit and a crucial platform for gamers, it’s less resonated than in 2021, stemming from the reduced time limit to 1 hour per day on weekends. In addition to the sensationalist motion and the generic format used, the SoCS meme achieved Berger’s venting and sense-making effects as well (Berger, 2014, p.592).anytimemakes

Back to topWith the ‘score’ a physical ‘consequence’ at any timeanytime, this may help vent Western gamers’ potential sense of alienation to the policy and makes sense of it – albeit in a less accurate and more eye-catching way.

Closing Out

The effects of the SoCS memes are two-fold in building a commuity. On one hand, they are a means for the West to make sense of the Chinese society, whose concept of a continuous surveilance system on citizens sounds alien to those under a more indiviudalistic and private setting. With the overarching system compressed in replicable images, their underlying fear is summarized, while also being the 'in-the-know' device in finding those who have a similar emotion. This eventually fulfills the identity-signalling function of sharing in Berger (2014, pp.589-90), conveying them as those wary and critical of the situation, even when the medium through which this sense is obtained is not always accurate. As a Reddit commentator on Zhou's Vice article wrote:

However, Chinese netizens – part of the subjects the memes parodied – are less sold on the idea. T,he miscredited origins of the meme, plus China's complexity and opagueness in administratation, makes them more skeptical to the existence of such a system, or even tired of hearing it as a generalization to the whole country. in discussingtoDespite not having the same "common ground" (Berger, 2014, p.591) as the West, this skepticism shapes a distinquisher between them and waibin 外賓 [foreign guests]: The foreigners who deem themselves knowing all of the Chinese society, but their understandings are limited to skin-deep portrayals like these memes. As previously analyzed, SoCS, Taiwan and June 4th Incident are the memes' recurring themes, but not the nation's other social problems. Relative to the Westerners repeating such, this makes Chinese netizens showing their disgust to these memes "more intelligent, competent, and expert" (ibid) than those self-claimed experts.

wemimicksdiscrepenciescreatesidentitesBeing an unexpected online phenomenon, the SoCS memes, like other viral internet texts, failed to make an impact on real-life political participation, especially when it's misdirected and uncertain about its accuracy over the policy's execution. Alas, one concept that persists throughout these variants is:

Nobody likes being watched over, 24/7.

Back to topReferences

Berger, J. (2014). Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24(4), 586–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2014.05.002.

Bond, N. (2022, July 4). John Cena’s relationship with Meme Culture, explored. The Ringer. https://www.theringer.com/wwe/2022/7/4/23186438/john-cena-wwe-20-years-….

Boom, D. V. (2021, May 26). John Cena’s China apology: What you need to know. CNET. https://www.cnet.com/culture/john-cenas-apology-to-china-everything-you….

Caldwell, D. [Don]. (2018, September 20). China's Social Credit System / +15 Social Credit. Know Your Meme. Retrieved May 28, 2023, from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/events/chinas-social-credit-system-15-so….

Carry, O. [Owen]. (2021, October 8). John Xina. Know Your Meme. Retrieved May 30, 2023, from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/john-xina.

Cockerell, I. (2022, July 13). Welcome to TikTok’s sanitized version of Xinjiang. Coda Story. https://www.codastory.com/disinformation/tiktok-xinjiang-sanitized-vers….

FRANCE 24 English. (2019, May 1). China ranks 'good' and 'bad' citizens with 'social credit' system [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/NXyzpMDtpSE.

Freedom, E. K. [@EnesFreedom]. (2021, October 25). XI JINPING and the Chinese Communist Party Someone has to teach you a lesson, I will NEVER apologize for speaking [Image attached] [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/EnesFreedom/status/1452405549438541830.

Gan, N. (2019, February 7). The complex reality of China’s social credit system: hi-tech dystopian plot or low-key incentive scheme? South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/2185303/hi-tech-dystop….

Goriunova, O. (2014). The force of digital aesthetics. on memes, hacking, and individuation. The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics, 24(47), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.7146/nja.v24i47.23055.

Harvey K. (2021, June 19). John Cena Speaking Chinese and Eating Ice Cream / Bing Chilling. Know Your Meme. Retrieved May 30, 2023, from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/john-cena-speaking-chinese-and-eating-ic….

JustOrdinaryMan. (2021, October 11). Super Idol 的笑容 [The Smile of A Super Idol]. Know Your Meme. Retrieved May 30, 2023, from https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/events/chinas-social-credit-system-15-so….

Kobie, N. (2019, June 7). The complicated truth about China's Social Credit System. WIRED UK. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from https://www.wired.co.uk/article/china-social-credit-system-explained.

kracc bacc. (2021, October 3). how to increase social credit [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/ZBDRIy4X2sU.

Lewis, R. (2017, September 26). Is Puerto Rico Part of the U.S? Here's What to Know. Time. https://time.com/4957011/is-puerto-rico-part-of-us/.

Rmon_34. (2022, February 16). Such a classic song [Online forum post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/SocialCreditMemes/comments/strtmb/such_a_class….

Roh, D. S., Huang, B., & Niu, G. A. (2015). Technologizing orientalism: An introduction. Techno-Orientalism, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.36019/9780813570655-002.

Shifman, L. (2013). Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a conceptual troublemaker. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18(3), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12013.

Shirke, R. (2022, January 31). Why is reddit an important source for gamers?. Into Indie Games. https://intoindiegames.com/features/why-is-reddit-an-important-source-f….

Soo, Z. (2023, January 20). China keeping 1 hour daily limit on kids’ online games. AP NEWS. https://apnews.com/article/gaming-business-children-00db669defcc8e0ca1f….

urfaselol. (2021, October 22). Enes Kanter doubles down on China and calls Xi to close down the Uyghurs Labor Camps [Online forum post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/nba/comments/qdk97o/enes_kanter_doubles_down_o….

Wertime, D. (Trans.). (2015, June 17). How to spot a state-funded Chinese internet troll. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/06/17/how-to-spot-a-state-funded-chinese….

wafflehusky. (2021, April 5). The user above me gets 15 social credit [Online forum post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/teenagers/comments/mko28i/the_user_above_me_ge….

watchfulsquad010. (2021, November 26). Wich movie is that? What do you mean by “it didn’t happen”? [Comment on the online forum post +69 Social Credits]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/memes/comments/r2gu06/comment/hm4xvgh/.

weebzeewastaken. (2021, October 9). I made this dumb meme into a real game [Online forum post]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/SocialCreditMemes/comments/q4a9ao/i_made_this_….

Young-Plague. (2021, October 25). Sure we might not fully understand, but we get that it’s inherently wrong [Comment on the online forum post Thank you VICE very cool]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/dankmemes/comments/qfpkux/comment/hi13jwe/.

Zhou, V. (2021, October 25). People don’t understand China’s Social Credit, and these memes are proof. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/pkpe3z/china-social-credit-meme.

Back to top