Anne Frank - myth or author?

In this article, we analyze whether the American image of Anne Frank connects to her self-posture in her life narrative 'Het Achterhuis'. Since there is little connection between the two, we conclude that the American image has become a myth.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

What were you doing when you were thirteen years old? In 2007, when I was that age, I made my first airplane flight, I was just going to my first year of high school and still played with Barbies after school. However, there were times when kids in the Netherlands weren’t so free and fortunate. Someone who wasn’t able to travel or even go to school at thirteen was Anne Frank.

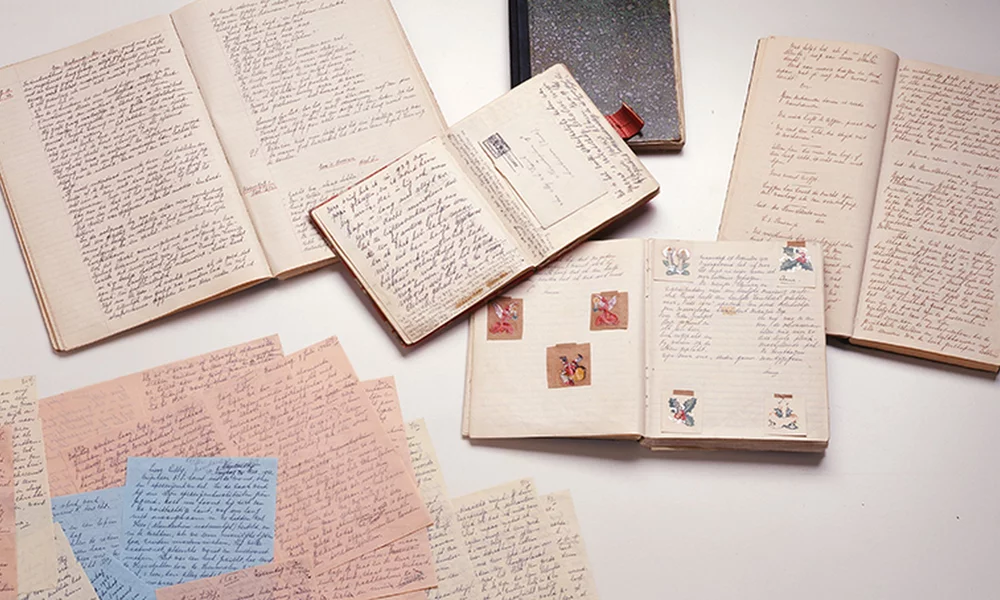

Anne is a German-Dutch girl who became famous for her life narrative ‘Het Achterhuis’ (translation: the Secret Annex), which was published after her death in 1947 by her father Otto Frank as the only Holocaust survivor of the family Frank. When Anne got a diary on her thirteenth birthday, shortly after that, on the sixth of July, 1942, the Frank family went into hiding in the Secret Annex (“Who was Anne Frank”, n.d.). In this diary, and the ones that followed, Anne wrote about her life in hiding. In 1944, the Secret Annex was discovered by the Gestapo, and the family got arrested and split up in different concentration camps. In February 1945, Anne died of typhus in concentration camp Bergen-Belsen.

Nowadays, Anne Frank is known for her legacy where she is praised as a “universal symbol of tolerance, strength, and hope in the face of adversity” (Anne Frank Center USA, n.d.). After her publication and celebrity because of it, a museum, statue, foundation, and actual award were established in her name. Anne became an icon, a source of inspiration as human rights advocate (Shandler, n.d.). However, her image might be more than iconic. It could tell us something about how society copes with history and meaning-making. Therefore I questioned: could the American image of Anne Frank be based on a myth or does it connect to her posture in her life narrative ‘ Het Achterhuis’?

Meizoz and Barthes

To answer the questions above — about the image of Anne Frank and whether it’s truthful to her posture — we need to fully understand what posture is and how it is created. First to help us with that is literary scholar Jérôme Meizoz (2010). He explained that with every word, action, and appearance, identity or representation of authorship is created. This ‘posture’, refers to “one or several discursive ethos(es) which participate in its construction” (Meizoz, 2010). In other words, it is the identity that an author ascribes to him or herself and is co-constructed with various mediators (Meizoz, 2010). Since Anne Frank, unfortunately, is not with us anymore, the posture that she created is a post-factual reconstruction based only on her written word. The difference with an ‘image’ is, that the latter are representations of someone created by others rather than the person (or author) itself (Dera, 2015). In our case, this means, most biographies or mediates create an image for Anne based on the posture she represented us in her book ‘Het Achterhuis’ or other short stories.

What makes this article on the persona of Frank so complex, is the way her image and extraordinary story are inseparably connected to her authorship. As Moran (2000) explained, “an almost inseparable connection between the author’s life and work” often comes with a status of celebrity in authorship — like Anne’s literary work is her life and her life is her work. Next to that, Anne never got a chance to present herself in public after receiving the role of a published author, her character or posture leaves a lot of room for interpretation and idealization (Sion, 2012). She spoke to and inspired so many, from musicals to museums, dance to fine art, and radio programs till tulip names, that those elaborated connections themselves, became a worthy phenomenon of wide-ranging engagement: the Anne Frank Phenomenon (Shandler, 2012a). Although many factors might have influenced the creation of this phenomenon, most are believing to attend one of Anne’s last wishes:“I want to go on living even after my death! And therefore I am grateful to God for giving me this gift, this possibility of developing myself and of writing, of expressing all that is in me.” (Frank as cited by Shandler, 2012a).Anne’s celebrity status, which now proved to be rather iconic as she stands the test of time, is something she always dreamed of (Shandler, 2012a).

However, the de-historized presentation of herself might not be what Anne dreamt of after all. When we look at receiving a certain kind of idealized image to someone or something, Barthes' theory on mythologies comes to mind. He explained (Barthes, 1991) how some objects or people are stripped of their historical, social, and/or functional context and are filled with a different meaning, becoming a “second-order signification” (Barthes, 1991). For example, a horseshoe is a tool to prevent wear on the hoof of horses. However, somewhere along the line, its meaning gained the symbolism of good luck. The added meaning has nothing to do with its actual purpose. A myth deforms and alienates the meaning of something by depriving it of its memory (Barthes, 1991) and imbuing it with some ideology. All the unanswered questions on Anne’s personality, as implied before, led to a certain idealization of her. Because nowadays we see this most strongly in the United States, we will look at American sources to see if there is any myth-making going on.

Image versus posture

In times of COVID-19, people are looking back at Anne, identifying with her situation, and finding comfort and courage in her words (Grisar, 2020). Generally, Anne’s image is built upon these six criteria: her intelligence, her documented development as a person, her sensitivity, her perceptivity, her self-knowledge through reflection, and pure intention (Steenmeijer, A. G., Frank, O., & van Praag, H., 1981). To find out how the Americans embrace Anne’s image and answer our research question, we will first be looking at a recent article of Forward as exemplary for the American image-making of Anne Frank and compare it with her posture as seen in ‘Het Achterhuis’ (Frank, 1995) since that comes closest to her actual self-presentation.

Image

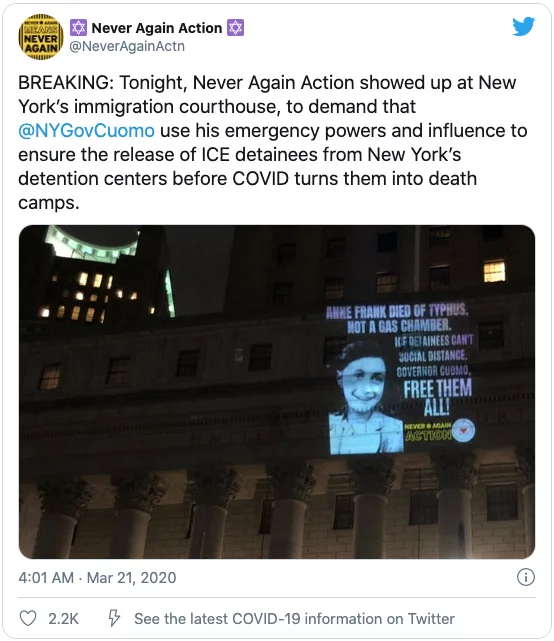

Our article begins with a plea of the Jewish activist group Never Again Action to release all detainees from an ICE detention center in New York. They are using Anne Frank, not only to compare her situation to that of the detainees but also to make the statement: “Without decisive action, [governors] Cuomo and Baker could create a humanitarian crisis that could cause the death of innocents” (Grisar, 2020). Judged on this, they are also indicating their use of Anne’s image as a protagonist of human rights to give force and a more striking effect to their statement.

Interestingly, Forward is very much emphasizing the accessibility of Anne Frank by highlighting personal stories on Twitter on how the public is relating to her in these modern times. They seem to gain a better understanding of Anne’s life in the Secret Annex during the COVID-19 lockdown(s). Some even found the inspiration to start a diary of their own, realizing that they too are living through what soon would become history (Grisar, 2020).

Not only (young-)adults are referring to Anne. Forward is explaining how all can relate to Anne, as most learned about her in a school setting. Teenagers are able to relate to Anne’s “clear, emotionally vivid descriptions of common childhood feelings and experiences'' (Grisar, 2020) as they experience those too (at that time in their life). Therefore we could say that youngsters learn about Anne in their childhood, and take that connection with them into adulthood. By using Anne’s image, activists like Never Again Action, can reach the youth and touch adults with their message. In this case, we could say Anne’s image is not only used for messages on victimhood, humanity, and protest, but also as a tool to reach a broader public.

In the last part of the article, Forward is suggesting we could all learn from Anne as she “endured for years against an enemy surrounding her” (Grisar, 2020), something that proved courage and inspires us to be so as well in times of COVID-19. According to Forward, while reflecting on a quote of Anne, we can get strength from her life narrative as her words “emphasize the urgency of optimism and the futility of fear” (Grisar, 2020) and help us answer our question with the experience she offered as an example of “resilience, kindness and grace” (Grisar, 2020).

When we look back at our six criteria (intelligent, developing, sensitive, perceptive, reflective, and pure intentioned) we can conclude not all are met in the Forward article. No comments are made on her intelligence, sensitivity, spirit, or reflectiveness. However, her development from child to young adult is mentioned extensively as this is the main criteria to which the American public relates with Anne. Interesting to this, is how this highlighting of one criterion is not a coincidence. Shandler (2012b) explained, that since the United States has never been under direct attack or Nazi control, they focus on other dimensions and praise her familiarity and accessibility, which is different from the European perspective on Anne (Shandler, 2012b). Anne’s perceptivity is often seen in the quotes Americans tend to use most when talking about Anne. One of those for example is: “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart” (Frank as cited by Hoffstein, L.S. & Devitt, A., 2018) or “How wonderful it is that nobody needs to wait a single moment before starting to improve the world. Think of all the beauty still left around you and be happy” (Frank as cited by Wingrove, 2020). This different focus resulted in Anne becoming a role model, especially in these “unsure circumstances'' (Grisar, 2020). To conclude we can say that Anne Frank’s image created by the Americans mainly highlights those aspects that are relatable to a broad public and put her onto a pedestal as a role-model for younger voices and human rights.

Posture

To analyze Anne Frank’s posture, we will take a look at three diary entries of ‘Het Achterhuis’ (Frank, 1995). All selected entries are out of the year 1994: January sixth, March 29th, and April fifth. When we start looking at our first entry in January, her way of telling grabs our attention. She starts with: “Today I have two things to confess. It's going to take a long time, but I have to tell them to someone, and you're the most likely candidate, since I know you'll keep a secret, no matter what happens” (Frank, 1995, January 6, 1944).

It feels like we (the readers) are her friend, she is telling her thoughts to us in confinement, which immediately gives a feeling of intimacy and creates a bond between the writer and reader. In this entry Anne tells us about her difficult relationship with her mom, her curiosity towards the same sex, both mentally and physically, and her changing body and personality during puberty. For example, this day Anne is telling about her menstruation as something dear to her: “Whenever I get my period (...), I have the feeling that despite all the pain, discomfort and mess, I’m carrying around a sweet secret” (Frank, 1995, January 6, 1944). At the time Frank is fourteen years old, and her ‘period’ is a physical sign of Anne growing from little girl to woman.

In March, it stands out how Anne’s way of writing changed. She starts by explaining her day, as she had always done, however, this day gives her a reason to progress into a different style. Afterward, she goes on to explain the general situation in the Netherlands at that time. How there is not enough food, how there is a lot of theft, and how the war in itself is increasing (with bombings on IJmuiden and the invasion of the Germans). The particular event, as Anne described in her diary, that led to this change is the following:

“Mr. Bolkestein, the Cabinet Minister, speaking on the Dutch broadcast from London, said that after the war a collection would be made of diaries and letters dealing with the war. Of course, everyone pounced on my diary. Just imagine how interesting it would be if I were to publish a novel about the Secret Annex” (Frank, 1995, March 29, 1994).

This leads us to believe Anne’s intentions are not as ‘innocent’ as generally described.

Lastly, in April, Anne emphasizes how much she wants to be a writer and gives us some insight into how she plans to become a great one. She believed that with her own reflection, she could learn and improve: “I’m my best and harshest critic. I know what’s good and what isn’t” (Frank, 1995, April 5, 1944). The result of her document proves we could say Anne was capable of looking at her own work rationally to improve her writing. Since Anne wrote about what she thought, experienced, or said, indirectly her work reflects her moral principles. Therefore being critical of her work meant also being critical of how she could improve as a person (Charnow, 2012). Although the overall tone of this entry is quite light-hearted, when we look more closely at her sentences, we notice underlying feelings. For example, in this sentence “When I write I can shake off all my cares. My sorrow disappears, my spirits are revived!”, it seems she is thankful for her writing, however, she also admits she has a lot of worries and sorrow that she does not seem to be able to shake off otherwise. Followed up with: “...will I ever become a journalist or a writer?”, questioning her future, whether there is one for her. Hence, Anne is not always as positive as she leads on to believe.

Although these selected passages can never showcase every piece of Anne’s posture and how she presented herself, when we look at our criteria (intelligent, developing, sensitive, perceptive, reflective, and pure intentioned), we can see that a lot have been met. She describes her development, both physically and mentally. Her sensitivity is confirmed through her detailed description of her feelings. Her continuous reflectiveness — most often rational, sometimes harsh — on her personality and her work as a writer. And lastly, her intentions. Although these are not ‘pure’, they aren’t less authentic. Anne was conscious of a potential public, proven by the fact that she started editing and rewriting earlier diary entries and formulating a prologue dated June 20, 1942 (Shandler, 2012b). Both versions, before and after March 29th, show differences in content, form, and readership.

Any (dis)connection

As we lay both lists of met criteria (of the image and posture of Anne Frank) next to each other, we see that each contains a different focus. Whereas her image talks about Anne’s development and perceptivity, her posture is about development, sensitivity, and reflectiveness. If we are to look at what other character traits are appointed or visible, we see that those too are very different. Her image tends to focus mostly on familiarity, relatability, and accessibility, whereas the posture of Anne can be extended with traits like positivity, witty, and intelligence. Although they both entail the criteria of development, we can conclude that Anne’s American image and posture do not connect.

Something that might have helped this disconnection is the ignorance of Anne’s wishes on the publication of her life narrative. As we have established above, Anne was very aware of a potential audience and did write ‘Het Achterhuis’ with the intention to be published. In her diary she wrote down how she decided to title her book: “The title alone [the Secret Annex] would make people think it was a detective story” (Frank, 1995, March 29, 1944). However, contrary to the American image of an ‘ever-developing’ Anne, countries like the United States did feel the urge to change the title from ‘Het Achterhuis’ — Frank’s preferred title — to a name with the word ‘diary’ in it (Shandler, 2012b). By changing the title to ‘diary’, the public is “foregrounding the author and the genre” (Shandler, 2012b), connecting Anne’s name to her writing and therefore strengthening her idealization and myth-status.

However, only criticizing the American image of Anne Frank wouldn’t be right. It is no secret that ‘Het Achterhuis’ is not only the work of Anne herself but also that of her father, Otto Frank since he is the one who regulated her story intensely after Anne’s death (Anne Frank House, n.d.). Before ‘Het Achterhuis’ was published, the life narrative was edited by multiple editors to develop from diary to typescript, to eventually a novel (Shandler, 2012b). However, calling ‘Het Achterhuis’ unauthentic and therefore unable to represent the posture of Anne, is incorrect. Anne did really represent her posture, her true self, and identity, in her diary. In the last diary entry of ‘Het Achterhuis’ Anne explains how this came to be:

“As I've told you many times, I'm split in two. … I'm afraid that people who know me as I usually am will discover I have another side, a better and finer side … I know exactly how I'd like to be, how I am . . . on the inside. But unfortunately I'm only like that with myself” (Frank, 1995, August 1, 1944).

Meaning, Anne did choose to present herself differently, more like the person she wants to be. Otto Frank confirmed this by explaining he was very surprised when reading Anne’s diary after the war: “It is quite a different Anne I had known as my daughter” (Anne Frank House, 2009). She was much more serious than how he knew her during her life.

The myth in the making

All in all, we can confirm that the American image of Anne Frank has become a myth. As seen above, we analyzed both posture and image and concluded that those did for the most part did not connect to each other. The de-historized presentation of Anne in the United States as “famous combatants for peace and tolerance” (Sion, 2012) is in line with icons like Mother Teresa (Sion, 2012) and not based upon her ‘actual’ posture and life. They have stripped Anne from her temporality and historical context — as a unique case being able to hide for the Gestapo (Cohen, n.d.) — and change her image into something eternal — the face of the whole holocaust and all its victims. It is not surprising, however, that it still connects with Anne in some ways as a “myth doesn’t seek to show or to hide the truth when creating an ideology, it seeks to deviate from the reality” (“Mythologies”, n.d.). The use of Anne Frank in the United States for purposes like the inspiring role-model for youngsters, education programs on discrimination and other victimization and humanism causes, informs us that she is a myth (in the making) indeed.

References

Barthes, R. (1991). Mythologies. New York: The Noonday Press.

Charnow, S. (2012). Critical Thinking: Scholars Reread the Diary. In: Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. & Shandler, J. (Eds.), Anne Frank Unbound: Media, Imagination, Memory (p. 291-308). Bloomington: Indiana University Press

Frank, A., Frank, O. H., Pressler, M., & Massotty, S. (1995). The diary of a young girl: the definitive edition (1st ed.). Doubleday.

Meizoz, J. (2010). Modern Posterities of Posture. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, p. 81 - 93. In: Gillis J. Dorleijn, R. Grüttemeier en L. Korthals Altes, Authorship Revisited Conceptions of Authorship around 1900 and 2000. Leuven.

Moran, J. (2000) Introduction: the charismatic illusion, pp. 1-14. In: Star authors. Literary celebrity in America. London: Pluto Press.

Shandler, J. (2012a). Introduction: Anne Frank, the Phenomenon. In Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. & Shandler, J. (Eds.), Anne Frank Unbound: Media, Imagination, Memory (p. 178-192). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Shandler, J. (2012b). From Diary to Book: Text, Object, Structure. In: Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. & Shandler, J. (Eds.), Anne Frank Unbound: Media, Imagination, Memory (p. 25-58). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Sion, B. (2012). Anne Frank as Icon, from Human Rights to Holocaust Denial. In Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. & Shandler, J. (Eds.), Anne Frank Unbound: Media, Imagination, Memory (p. 178-192). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Steenmeijer, A. G., Frank, O., & van Praag, H. (1981). A tribute to Anne Frank. Shogakukan.

Back to top