.jpegcfd7.webp)

Why Is The Internet So Obsessed With Moo Deng?: Parasocial Relationships and The Internet’s Favorite Hippo

Moo Deng, the internet’s favorite baby pygmy hippo, has captured millions of hearts worldwide. Her playful antics and rosy-cheeked charm highlight a growing trend: parasocial relationships with animals as emotional escape in our digital age

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

.jpegdd9c.webp)

“Do not yell my name or expect a photo, just because I’m your parasocial bestie,

or because you appreciate my talent.”

“Your ta- what is your talent?”

“Having a slippery body that bounces.”

(Saturday Night Live, 2024)

You might have seen images of a small, moist and chubby pygmy hippo around on the internet. If not, perhaps the name “Moo Deng” might ring a bell? This rosy cheeked raging baby hippopotamus has even been named in the NY Times 63 most stylish people of 2024 list . Moo Deng’s rapid rise to international fame reflects a growing cultural phenomenon: animals, particularly baby animals, are emerging as sources of mediated intimacy and emotional support. This article examines how parasocial relationships with animals on social media create a new form of mediated intimacy, using Moo Deng as a case study. Unlike relationships with human influencers, animals offer emotional refuge and a sense of authenticity that feels unfiltered and pure. By exploring Moo Deng’s viral success, this article analyzes the role of escapism, emotional safety, anthropomorphism, and the tension between public and private life in shaping these relationships. Finally, I argue that Moo Deng represents a unique form of digital connection, revealing shifting boundaries of intimacy, authenticity, and audience behavior in online culture.

Back to topYour parasocial bestie

Parasocial relationships, a concept first introduced by Donald Horton and Richard Wohl in 1956, describe one-sided relationships where a person feels a deep personal connection to a media figure such as a radio or TV star or the later emerging online influencer, who does not actually know they exist. These relationships rely on a kind of illusion: the media figure creates a sense of face-to-face interaction, making the audience feel seen and personally connected, even when the exchange is entirely mediated through a screen (Horton & Wohl, 1956, p.215).

For a parasocial relationship to form, a few key aspects are necessary. First, there has to be a consistent media presence: the figure needs to show up regularly in content the viewer consumes, creating familiarity and routine. Over time, this repeated exposure builds trust and emotional investment as the audience comes to perceive the figure as relatable and reliable. Media content often plays a critical role, offering personal glimpses or “behind-the-scenes” moments that make the connection feel even more intimate. Meanwhile, parasocial interactions -fleeting, seemingly personal exchanges like a TV host talking directly to the audience through a camera - help create a feeling of closeness and engagement, setting the stage for the deeper parasocial bond to be created (Giles, 2002 pp. 279-292; Horton & Wohl, 1956, pp. 215-218).

While parasocial relationships with human figures have been well-documented, the dynamic shifts in fascinating ways when the subject is an animal. Anthropomorphism -the act of projecting human-like qualities onto animals- plays a big part in this process (Haas & Kotrschal, 2015, pp. 167-169). When viewers watch the pygmy hippo Moo Deng “playfully bite” her zookeeper’s knees or run around her enclosure they interpret her behavior through a human lens, attributing emotions such as joy, curiosity, or affection to her actions. This humanization makes Moo Deng more relatable and endearing, allowing audiences to form emotional bonds similar to those they might have with human media figures.

Naturally, parasocial relationships with animals also have limits. Unlike a human celebrity, Moo Deng cannot acknowledge her fans or interact directly with them. She will never “like” a comment or respond to a shoutout and yet, this does not stop viewers from feeling connected to her. Real-world interactions, like visiting Moo Deng at the zoo or watching her 24-hour livestream, add a new layer to the parasocial bond. These tangible experiences make the connection feel more real than just digital interactions, though they also raise ethical concerns. After all, animals like Moo Deng can’t consent to this level of constant observation, even if she seems perfectly content wobbling around her enclosure.

Back to topMoo Deng’s rise to fame

Moo Deng from Thailand’s Khao Kheow Open Zoo, rose to international fame thanks to a carefully curated online presence and her irresistible personality. According to Atthapon Nundee, Moo Deng’s zookeeper, the goal was clear from the start: “The moment I saw Moo Deng born, I set a goal to make her famous, but I never expected it would spread abroad.” (Ratcliffe, 2024). Initially intended as a local sensation in Thailand, Moo Deng quickly captured global attention through viral content featuring her ferocious antics, rosy cheeks, and playful demeanor.

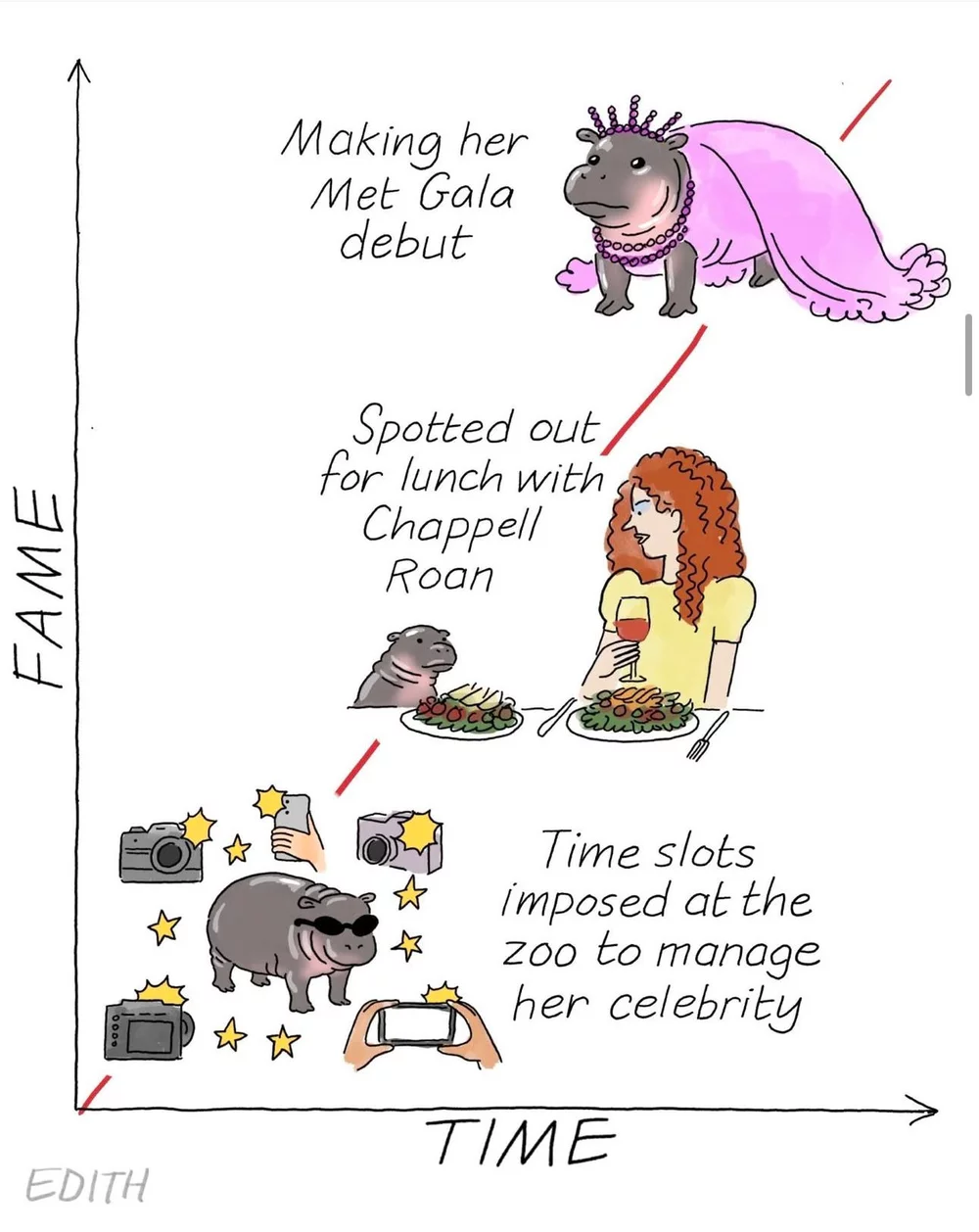

The numbers reflect the scale of her success. Gaillot & Tarasova (2024) stated that Moo Deng was mentioned in over three million posts worldwide within a single week, with 95% of the content being reposts of her videos and photos. Her fame transcended borders, turning her into a global icon. Gaillot & Tarasova report: “From January 1 to November 11, 2024, there were almost 6 million mentions of Moo Deng across all languages and channels, including social media, digital and broadcast news, blogs, and forums.” In that she rivals pop princess Chappell Roan, with only one million less mentions than the adult human being with a music career.

Moo Deng’s appeal also coincided with a broader trend in animal-focused content. Around the same time, another baby animal, Pesto the king penguin, went viral for appearing abnormally large in comparison to adult king penguins (Turnbull, 2024). Unlike Moo Deng’s chaotic, playful energy, Pesto’s popularity stemmed from his gentle and oddly oversized presence, demonstrating that mediated intimacy with baby animals takes diverse forms.

Back to topYour favorite emotional support animal

But why find comfort and joy in parasocial relationships with animals, when there are so many human options out there to fulfill these emotional needs? After all, people are easier to relate to, strong parasocial relationships are often based on similarities (Stein et al., 2024, pp.3436-3438) and there is a tiny chance they might someday be aware of one's existence. What is the allure of a baby pygmy hippo? Looking at what the recent digital landscape offers its users, it’s an overwhelming amount of bad news and negatives. There is a lot of chaos in the world right now, and focusing on a feisty baby hippo offers users a break from other pressing issues presented online. Moo Deng has emerged as a comforting presence providing emotional refuge to her global audience. Forming parasocial relationships with animals like Moo Deng fulfill an unique emotional need: they offer safe, uncomplicated intimacy that allows viewers to disconnect from stress, anxiety, and the unpredictability of human relationships and world events (Sriyai, 2024). This phenomenon is deeply tied to the concept of escapism; using simple, joyful content to find relief from the pressures of daily life.

Moo Deng’s presence feels particularly significant during times of social or personal uncertainty. Viral videos of her slipping around and swimming with her mother align with research (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2015; Bromberg-Martin et al.,2010) showing that exposure to uplifting content activates the brain’s reward systems, releasing dopamine and fostering feelings of calm and satisfaction. Watching Moo Deng or engaging with memes about her, with her wobbling movements and expressive face, provides an emotional reset, helping viewers manage their stress through shared moments of joy.

Furthermore, Moo Deng’s consistent online presence through viral videos, livestreams, and zoo updates creates a sense of stability and predictability. Her regular appearances allow viewers to incorporate her into their emotional routines, much like checking in on a friend. This continuous access deepens the parasocial relationship, transforming Moo Deng into a dependable source of company. As Sriyai (2024) highlights, animal-focused viral trends also foster a sense of community and belonging, as people bond over their shared affection for figures like Moo Deng.

In this way, Moo Deng provides more than fleeting entertainment, she becomes an integral part of her audience’s emotional landscape. Her content serves as a reminder of simplicity and joy, offering escapism and support in a non-demanding, judgment-free form. This mediated intimacy, rooted in innocence and emotional purity, highlights why animals like Moo Deng are uniquely positioned to fulfill psychological and emotional needs in digital culture.

Additionally, the community aspect of following Moo Deng’s online presence contributes to the feeling of emotional safety. Fans and followers often share their experiences and emotions in comments and discussions, creating a supportive and like-minded community. This shared experience fosters a sense of belonging and solidarity, as individuals come together to celebrate and adore Moo Deng. The positive interactions within this community amplify the emotional benefits, creating a collective space of comfort and escape.

Back to top

Cuteness, innocence, and authenticity: The appeal of Moo Deng

Thus, it’s established that Moo Deng offers emotional escape, but what characteristics make her the right hippo for the job? Moo Deng’s appeal as a parasocial figure is grounded in her overwhelming cuteness, her perceived innocence, and an undeniable sense of authenticity. These qualities, which are prominent in baby animals, evoke strong emotional responses that deepen the parasocial bond and make her a particularly powerful source of mediated intimacy.

The “cuteness factor” is one of the most immediate and impactful aspects of Moo Deng’s appeal. As research (Kringelbach et al, 2016, pp. 545-549; Lv et al., 2022, p.2; Zhou et al., 2024, pp.1-2) explains, cute imagery -characterized by round shapes, small size, and soft features- activates caregiving instincts and triggers the brain’s reward systems. Moo Deng’s small, chubby body, rosy cheeks, and wobbly movements align perfectly with this definition, making her incredibly endearing. This instinctive response encourages viewers to engage with her content repeatedly, strengthening the parasocial connection over time.

In addition to her cuteness, Moo Deng embodies innocence and purity. Animals, particularly young ones, are perceived as free from the complexities and social expectations that shape human behavior (Sriyai,2024). Moo Deng’s playful antics are interpreted as genuine and unfiltered expressions of emotions.

Nicholson (2024) and Giles (2012, pp.115-118) highlight that parasocial relationships with animals are particularly stable because animals cannot tarnish their image or betray audience trust. Moo Deng’s inability to engage in controversy or audience deception reinforces her role as a safe and dependable figure of joy. Her authenticity is further amplified by her lack of any performative intent, as she cannot “fake” her emotions or actions, which contrasts sharply with the highly curated personas of human influencers. In this way, Moo Deng’s cuteness, innocence, and authenticity work together to establish a profound emotional bond with her audience. These qualities set her apart from human media figures, highlighting why parasocial relationships with animals like Moo Deng offer a uniquely fulfilling form of mediated intimacy.

Back to topThe price of authenticity

However, while Moo Deng can be considered as entirely authentic, the people around her might not be. Her zookeeper did admit to wanting to make her famous, and has done so successfully. In videos, he often teases her which then causes an energetic reaction from her. This is exactly the kind of content people want to see, and Moo Deng being ‘full of rage’ or ‘horrified’ is a reoccurring theme in memes about her. While arguably the teasing can be defended by the fact that her zookeeper has to desensitize her, one cannot deny that he and the zoo benefits from her content. As long as her videos get views, Nundee gets some revenue from it, and the zoo gains popularity. Ticket sales doubled, the zoo sells merch dedicated to her, and to accommodate for the rising amount of visitors, people are only allowed to watch Moo Deng for 10-15 minutes in groups of 30-60 people. Moo Deng has been harassed by visitors who wanted her to be more active on two different occasions (Foley & Riffe, 2024). As she is a baby, she sleeps for most of the day. Yet, this does not align with the curated persona the visitors have grown to love. Thus, the parasocial relationship creates a sense of entitlement in these visitors, who demand she ‘performs’ as expected. Moo Deng’s exposure remains beyond her control. Unlike human influencers, she cannot consent to being constantly watched, livestreamed, or visited, which raises concerns about the boundaries between care, entertainment, and exploitation.

Back to topConclusion

Parasocial relationships with Moo Deng highlight the evolving nature of mediated intimacy in a digital world. While parasocial relationships are often focused on humans, baby animals have proved their potential even though the grounds of the parasocial relationships might be different. Moo Deng’s cuteness, innocence, and perceived authenticity offer audiences a safe emotional outlet, providing joy and escapism amid global chaos. However, Moo Deng’s fame also exposes the tensions inherent to animal-focused content: her life is curated for human consumption, often blurring boundaries between care and entertainment. As animals like Moo Deng become central to online culture, one must question how their stories are shaped, who benefits from their exposure, and what responsibilities audiences hold in engaging ethically with mediated content. Moo Deng’s success serves as both a source of delight and a mirror reflecting our complex relationship with authenticity, intimacy, and digital media. Long live our moist icon!

References

Berridge, K., & Kringelbach, M. (2015). Pleasure systems in the brain. Neuron, 86(3), 646-664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.018

Bromberg-Martin, E. S., Matsumoto, M., & Hikosaka, O. (2010). Dopamine in motivational control: Rewarding, aversive, and alerting. Neuron, 68(5), 815-834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.022

[@CookCapitalLLC].Cache://x.com/KookCapitalLLC/status/1855969066952872225 - Google search [Image]. (n.d.). X.com. https://x.com/KookCapitalLLC/status/1855969066952872225

Dunlop, E. [@emilydunlop.art]. (2024, November 15). Emily Dunlap | Artist 🥞🫧✨ on Instagram: "I’m excited to share that the ‘Familiar friends’ limited time print drop is now LIVE for public access! This collection will only be available up until November 21st. ♥️Visit link in bio to shop - - #art #hippo #oilpainting #pesto #moodeng #impressionism #oilpaint #pastel #monet #waterlily #artist #artprint" [Image]. Instagram. Retrieved December 12, 2024, from https://www.instagram.com/p/DCZVGLnvhYb/?img_index=1

Foley, B., & Riffe, N. (2024, September 24). Nytimes.com. The New York Times - Breaking News, US News, World News and Videos. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/24/style/moo-deng-baby-pygmy-hippo-thailand.html

Gaillot, A., & Tarasova, E. (2024, November 12). Is the moo Deng trend over? Meltwater. https://www.meltwater.com/en/blog/moo-deng-trend

Giles, D. C. (2002). Parasocial interaction: A review of the literature and a model for future research. Media Psychology, 4(3), 279-305. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532785xmep0403_04

Giles, D. C. (2013). Animal celebrities. Celebrity Studies, 4(2), 115-128. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2013.791040

Horton, D., & Richard Wohl, R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215-229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

Kringelbach, M. L., Stark, E. A., Alexander, C., Bornstein, M. H., & Stein, A. (2016). On cuteness: Unlocking the parental brain and beyond. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(7), 545-558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.05.003

Lv, X., Luo, J., Liang, Y., Liu, Y., & Li, C. (2022). Is cuteness irresistible? The impact of cuteness on customers’ intentions to use AI applications. Tourism Management, 90, 104472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104472

Nicholson, A. (2024, October 1). The rise of moo Deng has nothing to do with her cuteness. Mamamia. https://www.mamamia.com.au/who-is-moo-deng/

Nytimes.com. (2024, December 5). The New York Times - Breaking News, US News, World News and Videos. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/05/style/best-dressed-people-2024.html

Pritchett, E. [@postopinions]. (2024, October 9). Washington Post opinions on Instagram: ""The unstoppable rise of moo Deng, the internet’s favorite hippo," as drawn by @EdithCartoonist. 🦛 visit the link in our bio to see more cartoons and give Edith a follow!" [Image]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/DA6xwmTvfOj/

Ratcliffe, R. (2024, September 13). ‘I set a goal to make her famous’: The baby pygmy hippo who became a giant online. the Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/sep/13/moo-deng-hippo-tiktok-khao-kheow-open-zoo-thailand-viral

Saturday Night Live. (2024, September 29). Weekend Update: Baby Hippo Moo Deng on Fame - SNL [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vfIbbP3vuwA

Sriyai, S. (2024, October 8). Beyond fleeting fascination: How moo Deng and Butterbear offer escapism in hard times. FULCRUM. https://fulcrum.sg/beyond-fleeting-fascination-how-moo-deng-and-butterbear-offer-escapism-in-hard-times/

Stein, J., Linda Breves, P., & Anders, N. (2022). Parasocial interactions with real and virtual influencers: The role of perceived similarity and human-likeness. New Media & Society, 26(6), 3433-3453. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221102900

[@1989vinyl].TikTok [TikTok Video]. (2024, October 3). TikTok - Make Your Day. Retrieved December 12, 2024, from https://www.tiktok.com/@1989vinyl/video/7421670123351772462?q=moo%20deng&t=1734369996290

Turnbull, T. (2024, September 24). Meet pesto: The fat baby penguin and viral superstar. BBC Breaking News, World News, US News, Sports, Business, Innovation, Climate, Culture, Travel, Video & Audio. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cp3w4nld5e3o

Urquiza-Haas, E. G., & Kotrschal, K. (2015). The mind behind anthropomorphic thinking: Attribution of mental states to other species. Animal Behaviour, 109, 167-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.08.011

Zhou, F., Lin, Y., & Mou, J. (2024). Virtual pets' cuteness matters: A shared reality paradigm for promoting internet helping behaviour. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 202, 123308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123308

Back to top