Resisting food colonialism: Boba, TikTok and cultural appropriation

Boba or bubble tea originates from Taiwan and consists of tea, milk, and chewy tapioca pearls. Boba is not merely just a drink but a cultural symbol and an identity marker of Asian immigrant communities in the West (Zhang, 2019). When a Canadian company claimed to have transformed the traditional bubble tea into a healthier drink and pitched their idea on an episode of a “Shark Tank”-style reality TV show featuring Canadian-Chinese actor Simu Liu, backlash and conversations over cultural appropriation sparked online, particularly on TikTok (Halpert, 2024). This global appeal of boba while amplifying the visibility of Asian culture, also implies a deeper problem, related to how Asian cultural artifacts are extracted, appropriated, and colonized.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Boba or bubble tea originates from Taiwan and consists of tea, milk, and chewy tapioca pearls. Boba is not merely a drink but a cultural symbol and an identity marker of Asian immigrant communities in the West (Zhang, 2019). In recent years, along with a rising interest in boba, the global market has seen significant growth, allowing boba to achieve mainstream popularity (Zhang, 2019). Like many other ethnic foods popularized in the West that are often perceived through notions of authenticity and exoticness (Dreher, 2019), boba has been commodified and repackaged as a trendy, aesthetically pleasing product.

When a Canadian company claimed to have transformed the traditional bubble tea into a healthier drink and pitched their idea on an episode of a “Shark Tank”-style reality TV show featuring Chinese-Canadian actor Simu Liu, backlash and conversations over cultural appropriation were sparked online, particularly on TikTok (Halpert, 2024). This global appeal of boba, while amplifying the visibility of Asian culture, also implies a deeper problem related to how Asian cultural artifacts are extracted, appropriated, and colonized.

In this article, I argue that this case study falls under the category of cultural colonialism and explores the roles of social media platforms in resisting coloniality. Situating the case in a hybrid media system, where old and new types of media are intertwined (Chadwick, 2017), this article reflects on concepts of coloniality (Quijano, 2007) and cultural food colonialism (Heldke, 2001) to further highlight implications on the topics of visibility and representation of marginalized communities.

Back to topDragon’s Den, Bobba, and Simu Liu

The reality TV series in question is CBC’s “Dragon’s Den”, where “aspiring entrepreneurs pitch their business concepts and products to a panel of Canadian business moguls” (Dragons’ Den, n.d.). For the first time, the show welcomed celebrity guest Simu Liu to join for four episodes in Season 19 of Dragon’s Den (CBC Gem, 2024).

It is of crucial importance to highlight the significant influence of Chinese-Canadian actor and investor Simu Liu within the Asian communities as he is vocal about matters of Asian discrimination and representation (Handley, 2024). Simu Liu has a strong social media presence with over 2.4 million followers on TikTok (Liu, n.d.). This is relevant as he used his TikTok account to discuss the culture appropriation controversy in the case study, which will be analyzed later on in this article.

The episode that sparked online debate featured a Quebec-based drink company called “Bobba”, where the founders promoted their canned bubble tea product to potential investors as a healthier, more convenient take on the traditional drink (Halpert, 2024). Bobba’s entrepreneurs Sebastien and Jess argued that they were “disturbing” the bubble tea market with their “grab and go popping boba”. While other investors expressed support, Simu Liu raised concerns about cultural appropriation, questioning the implications of improving a drink rooted in Asian culture. This episode was aired on the Canadian streaming service CBC Gem and promoted on TikTok (CBC Gem, n.d.; Dragons Den, n.d.), where public backlash occurred. In response to the intense public attack, the entrepreneurs apologized on their Instagram page and acknowledged the cultural significance of boba to resolve their branding crisis (Bobba, 2024). Regarding the reactions of judges from Dragon’s Den, Simu Liu addressed the controversy in one of his TikTok videos, urging constructive criticism while discouraging online harassment of the entrepreneurs, while Manjit Minhas called off her investment in Bobba via her Instagram post (Halpert, 2024).

Back to topConcepts

Before going into further analysis of how this case study reflects cultural colonialism and explores the roles of social media platforms in digital resistance, it is essential to unpack the key concepts involved. First, this article draws on the concept of coloniality, which refers to the ongoing effects of colonization in the world today (Quijano, 2007). According to Quijano (2007, p. 169), although colonialism in terms of political domination has ended, the relationship between the West and the others “continues to be one of colonial domination”. He stated that colonial power created discrimination through racial, ethnic, and national categories. As these categories were rationalized, they stayed in our minds, so that “a colonization of the imagination of the dominated” (Quijano, 2007, p. 169). Coloniality then continues to influence modern society, shaping how power and knowledge are distributed.

Relating to coloniality and the boba case study is the notion of commodification of difference, which highlights how cultural elements from ethnicities are extracted and framed as “spice, seasoning that can liven up the dull dish that is mainstream white culture” (Hooks, 2015, p. 366). This process turns cultures from marginalized groups into profitable commodities that appeal to a broader audience while stripping off their original significance. Instead of promoting cultural appreciation, the “commodification of Otherness” reduces the differences to trends and benefits from the marginalized whose cultures are being appropriated.

Lastly, the idea of cultured food being colonized and commodified in the West prompts the concept of cultural food colonialism, which sees food adventuring – cooking or eating ethnic foods – as “part of a system of culture colonizing activity” (Heldke, 2003, p. xxviii). Heldke (2003) highlights the lack of “reflective attention” and ignorance of Euroamerican food adventurers toward the marginalized Others’ foods. She explains this attitude is due to the food colonizers’ “obsessive interest in and appetite for the new, the obscure and the exotic”, and that they treat cultures of the Others as resources (Heldke, 2003, p. 7).

This article will use a multimodal discourse analysis approach to analyze the boba case study (Diggit Magazine, 2020). Semiotic signs within the TikTok videos to be examined and uptakes enabled by TikTok platform affordances are loaded with indexicalities, which can inform the social meanings and broader implications of cultural colonialism.

Back to topBoba as a site of extraction

In the case study, boba is repackaged as a trendy commodity, stripped of its cultural origins, and thus serves as a site of extraction for Western food colonizers. In the pitch by Bobba, traditional boba is described as “that trendy, sugary drink you are queueing up for, and you are never quite sure about its content” (CBC Gem, 2024). By framing it as a “trendy” drink, boba is reduced to an aesthetic experience rather than a meaningful cultural product. Moreover, the entrepreneurs exemplify this framing by claiming that consumers do not know the content of their boba. This attempt to treat boba, particularly traditional boba from Asia, as a mysterious or even unsafe beverage to drink, signifies a superior state of mind. This is because “only European culture is rational”, therefore other cultures, which are different from the dominant, are inferior by nature (Quijano, 2007, p. 174).

This recalls historical patterns where food products from the East are identified as novel discoveries but often "othered" due to their differences. A prime example of this is perhaps the racialized panic of MSG (monosodium glutamate) in the United States in the late 1960s (Sand, 2005). From a letter titled "Chinese Restaurant Syndrome" published in a medical journal listing strange symptoms a doctor had whenever he eats at Chinese restaurants, MSG was then linked to unscientific health concerns and avoided by Westerners. While MSG - a flavor booster from Japan - was first considered enlightened and rational (Sand, 2005, p. 47), and used widely across the world, it eventually led to a racialized stigma around Chinese cuisine and, by extension Chinese American, reinforcing the notion that non-Western foods were inherently suspicious or unsafe to consume.

Following this statement, the two Canadian entrepreneurs from Bobba continued to argue that they have “transformed this beloved beverage into a convenient and healthier, ready-to-drink experience” and called their improvement “crazy innovations” (CBC Gem, 2024). By using phrases like “transformed” and “innovations”, they further distance boba from its traditional essence and reinforce the commodification of boba. Boba in their view is treated as a product in need of reinvention to appeal to global consumer tastes. Additionally, when being confronted by judge Simu Liu that their products lack the acknowledgment of the origin of boba and that the idea of making boba better is an issue of cultural appropriation, the company argued that “it’s not an ethnical product anymore” (CBC Gem, 2024). This remark erased boba’s Taiwanese cultural heritage and recast it as a generic commodity.

These claims by Bobba echoed the notion of cultural food colonialism (Heldke, 2003) and the commodification of difference (Hooks, 2015). According to Heldke (2003), ethnic foods are seen as discoveries when arriving in another culture and are subject to food adventurers’ conquest. In this case, boba is viewed as a resource for commodification that benefits the Western colonizers. The cultural significance of boba is then extracted and replaced by a better version, as stated by the entrepreneurs from Bobba: “We took the Asian version and we made it with fruit juice” (CBC Gem, 2024).

Boba as a site of extraction has been appropriated and commodified, aligning with broader patterns of coloniality, where the cultural narrative is diminished, and thus reduced to a consumable trend.

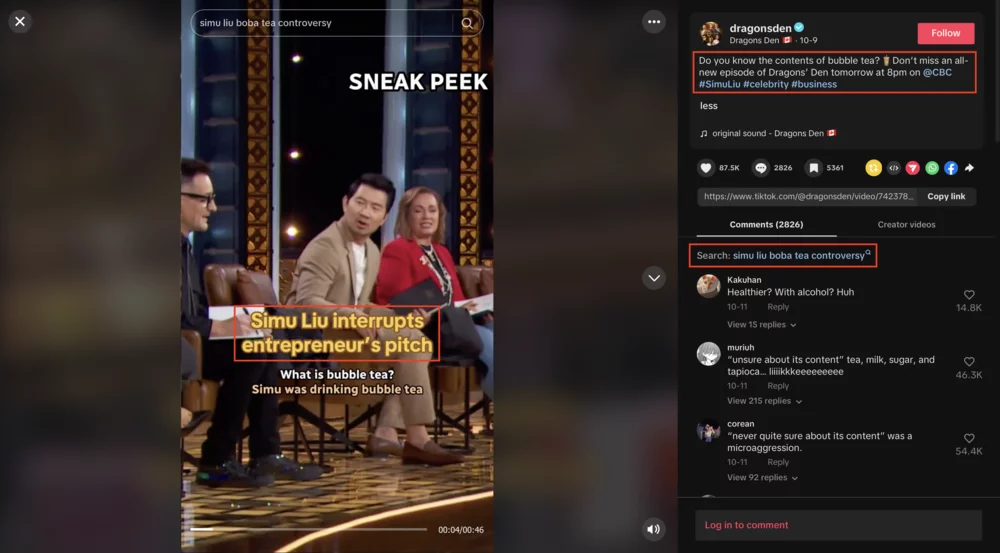

Interestingly, how this Dragon’s Den episode was promoted on social media also contributes to this particular framing of boba. In a sneak peek video cropped from the to-be-aired episode, which was posted on Dragon’s Den TikTok channel, the on-screen caption reads: “Simu Liu interrupts entrepreneur’s pitch” (Dragons Den, 2024). By positioning the only ethnically Asian judge in the panel in opposition to the Canadian entrepreneurs, this video seemingly indexed a discourse of “us” versus “them”. Moreover, the video description says: “Do you know the contents of bubble tea?”, implying that bubble tea is a mysterious drink, which triggers even more controversies. Together with hashtags like “#SimuLiu” and “#celebrity”, the show promoters successfully utilized TikTok platform affordances to boost visibility for this episode. This is also where the concept of a hybrid media system comes into play, as traditional media and new media co-exist (Chadwick, 2017). While Dragon’s Den was aired on television by Canadian broadcaster CBC, which represents traditional media, it was also promoted on TikTok to get circulated. By doing so, the episode got secondary exposure, therefore attracting more audiences’ attention and generating uptake. On the other hand, this hybridity between old and new forms of media allows us to look at how different actors and the media interplay in the changing landscape (Chadwick, 2017, p. 5). Although the drink company Bobba produced the message and CBC promoted the episode to steer public opinion in certain ways, its uptakes rely on the audiences and their interactions with the platform.

Back to topTikTok as a platform for colonial resistance

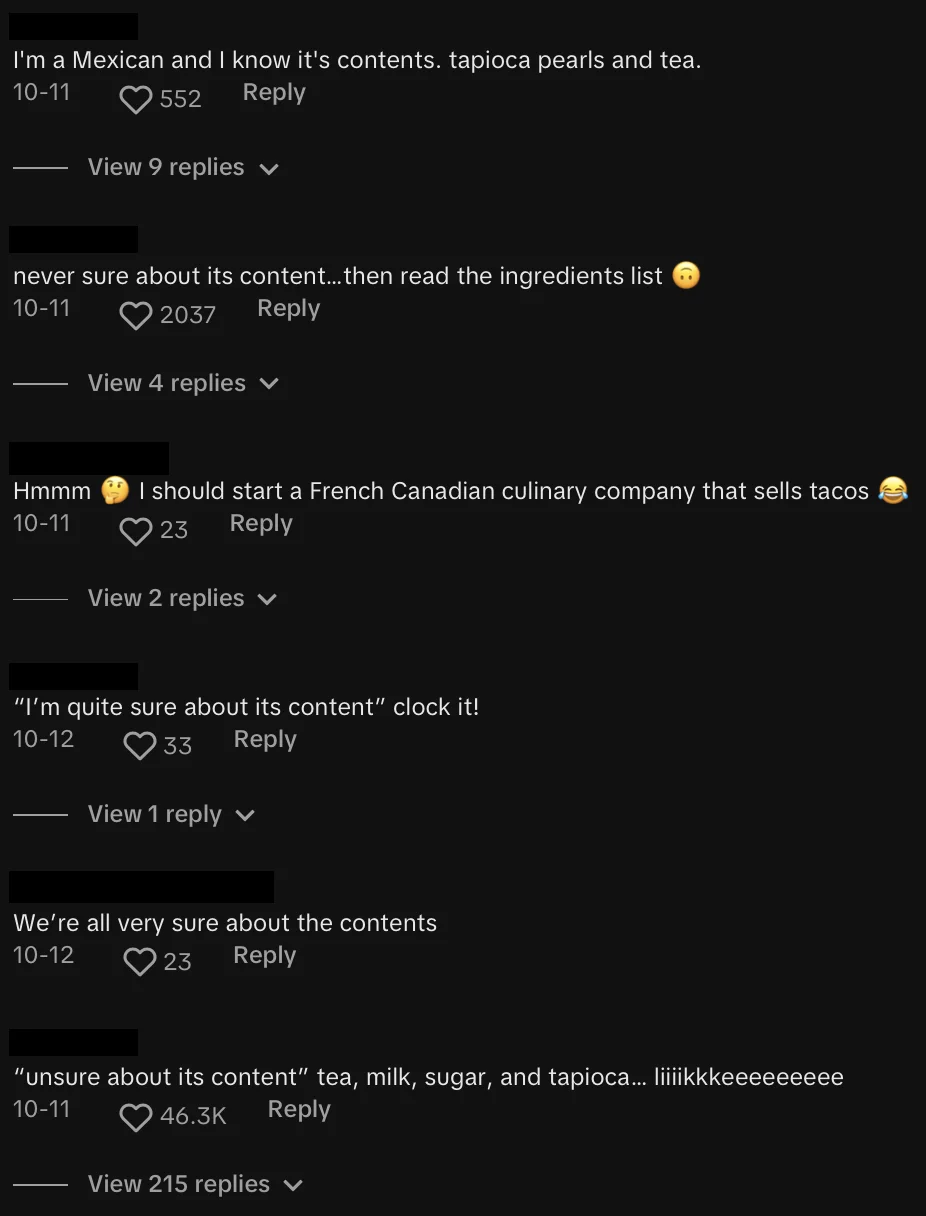

While this episode of Dragon’s Den successfully achieved popularity on social media with over 9.7 million views, 721.2K likes, 24.3 thousand comments, and 84.2 thousand shares (CBC Gem, 2024), the uptakes from online users were of negative sentiment. For instance, in the comment section under the TikTok video posted by CBC Gem, many users agreed with Simu Liu’s take on cultural appropriation and praised him for calling out Bobba. Similarly, the comment section of the sneak peek video posted on Dragons Den sees the same upsetting reactions with people criticizing the entrepreneurs’ cultural insensitivity and affirming they are quite sure about the content of boba.

Beyond direct commentary, TikTok users engaged in resistance by leveraging the platform's affordance. On TikTok, once a sound is made public, all other users can replicate and use it in their own videos. Parts of the entrepreneur's take on erasing the ethnical context off of boba were made into a sound, which many users started using to critique and expose this racialized logic (see Figure 2). This sound starts with the line: "It's not an ethnical product anymore" (CBC Gem, 2024). In these videos, users are seen enjoying their boba but calling it an "ethnical drink" and pairing it with the mentioned sound, sarcastically referencing the problematic Dragons Den episode.

The resistance against the show’s narrative can also be seen through the use of algorithm-generated search, hashtags, and a series of parody TikTok videos. As seen in Figure 3, many users who are not familiar with the incident can conveniently click the search term recommended by TikTok to learn more. Putting a famous actor’s name next to the word “controversy” can invoke TikTok users’ curiosity and tempt them to watch the episode in question.

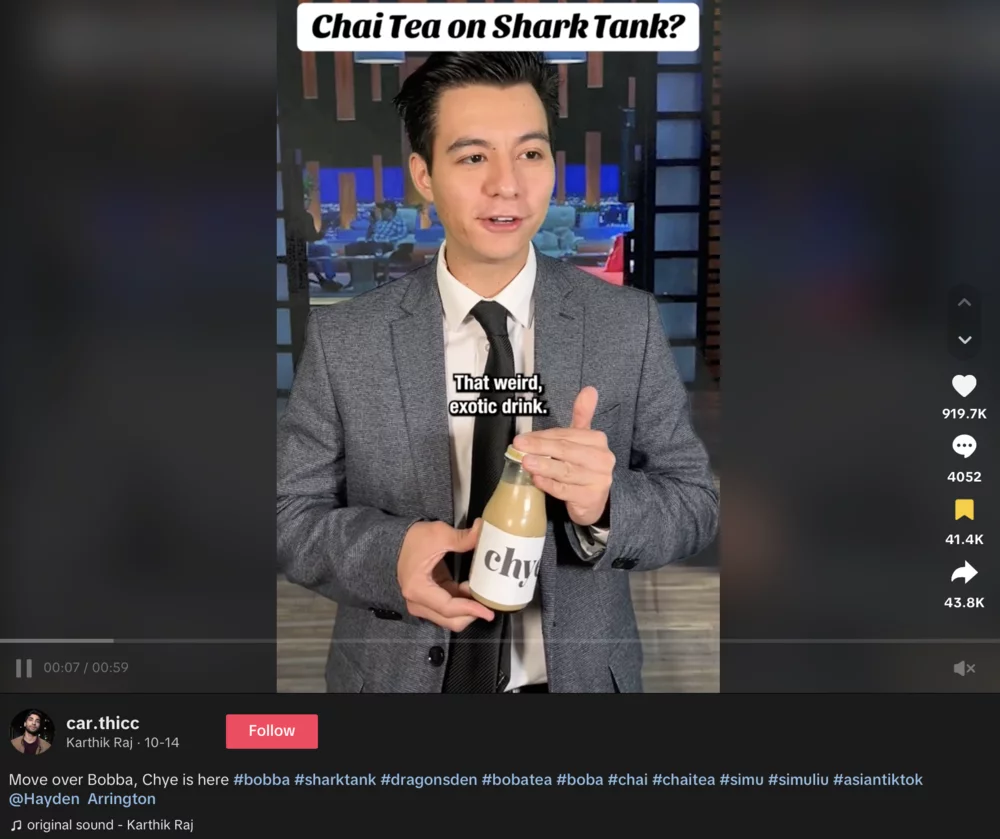

Within the search page, there are multiple parody videos made by online creators mimicking what happened in the Dragon’s Den episode, challenging the notion of boba colonialism. For instance, a creator humorously made a video about pitching chai tea on Shark Tank but calling it “Chye” (see Figure 4). The parody used the exact format as the Dragon's Den episode with confident business jargon and bold statements. In the video, chai is described as “that weird, exotic drink” and a bottled version of it called “Chye” is created “without all those weird spices that those people put in it” (Raj, 2024). The wordplay “chye” instead of “chai” echoed the way boba is branded as “Bobba” in the case study, sarcastically calling out the Canadian entrepreneurs in the Dragon’s Den episode. Using mimicry and satire as resistance, this example sparks debate and highlights the absurdity of Westerners' food colonialism discourse.

Additionally, by using hashtags like #bobba, #dragonsden, #simu, #asiantiktok, and #boba, this creator utilized TikTok algorithmic visibility to ensure that his video appears in searches related to the controversy. This allows his parody - designed to provoke engagement - to surface alongside bigger conversations about cultural appropriation.

Parodies on TikTok contribute to making discussions on pressing topics like food colonialism more accessible and engaging to users, since they are of comedic and short-form nature. This type of content is also a way of reclaiming the narrative around cultural foods and giving voice to marginalized communities. Once parodies gain enough attention from the public, they put pressure on the involved parties and make it impossible for the controversy to go unnoticed, demanding better cultural appropriation and acknowledgment from brands.

TikTok in this sense has enabled transnational community-building, allowing Asian diaspora communities to connect and affirm their cultural heritage. Through leveraging the platform's affordance and parody videos, they can challenge the appropriation and reclaim authentic cultural narratives.

Back to topChallenges and limitations

Happening simultaneously to this is another form of digital resistance, where many online users attack the entrepreneurs from Bobba, forcing Simu Liu to bring the matter to TikTok. In a video posted on his TikTok channel, he shared his thoughts on boba and Bobba, encouraging people to speak up on cultural appropriation but calling out extreme behaviors toward the entrepreneurs like sending death threats (Liu, 2024). This is one of the limitations of digital resistance where the line between constructive criticism and cyberbullying is crossed. The outcome of this in the case study is Bobba facing a branding crisis and losing its investment when judge Manjit Minhas decided to take back her financial support to Bobba (Minhas, 2024).

While social media platforms have contributed tremendously to the fight against food cultural colonialism, the proliferation of boba in Western countries creates a problem with commodification, in which “communities of resistance are replaced by communities of consumption” (Hooks, 2015, p. 375-376).

The boba case study is only part of a broader trend of food colonialism: reinventing ethnic foods to fit Western standards and profiting off of it. A similar narrative is seen in the arrival of matcha as a superfood discovery in the United States, where its Japanese cultural significance has been erased (Dreher, 2019).

Back to topConclusion

This case study highlights how cultural foods are often extracted, repackaged, and commodified for the benefit of the dominant, resulting in the erasure of their cultural origins. The framing of boba as a trendy drink and the discourse surrounding boba transformation exemplifies cultural appropriation and colonization of boba. Social media platforms, particularly TikTok, have demonstrated their potential for resisting these colonial dynamics. Through comments, hashtags, and parody videos, users are able to connect transnationally, criticizing Bobba’s cultural insensitivity and reclaiming boba’s cultural significance. This reflects how digital platforms can empower marginalized voices.

However, the case also reveals the limitations of digital resistance. Online backlash, while raising awareness, can escalate into harassment and cyberbullying. Ultimately, while TikTok offers space for resisting coloniality, it also exists within systems of commodification, where cultural elements lose their historical context and meaning to gain popularity in a white-dominated digital landscape.

Back to topReferences

Bobba [@bobbaofficiel]. (2024, October 13). We are very sorry for our delayed response and needed some time to reflect on the entire situation. This is [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/DBFG-Z5xE-8/?img_index=1

CBC Gem. [@cbcgem]. (2024, October 10). Part 9 | This bottled bubble tea business pitches to celebrity Dragon Simu Liu and the rest of the Dragons [Video]. TikTok. https://vt.tiktok.com/ZS66vcMo4/

CBC Gem. (2024, October 9). Actor Simu Liu is guest Dragon in the den! Here’s the kind of company he’s looking for. CBC Television.

CBC Gem. [@cbcgem]. (n.d.). CBC Gem is a free streaming service in Canada [TikTok profile]. TikTok. Retrieved December 20, 2024, from https://www.tiktok.com/@cbcgem

Chadwick, A. (2017). The hybrid media system. In Oxford University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190696726.001.0001

Diggit Magazine. (2020, February 13). Diggit Magazine. https://www.diggitmagazine.com/wiki/multimodal-discourse-analysis

Dragons Den. [@dragonsden]. (2024, October 9). Do you know the contents of bubble tea? Don’t miss an all-new episode of Dragons’ Den tomorrow at 8pm on [Video]. TikTok. https://vt.tiktok.com/ZS6rW8vVq/

Dragons Den. [@dragonsden]. (n.d.). Official TikTok of CBC’s Dragons’ Den [TikTok profile]. TikTok. Retrieved December 20, 2024, from https://www.tiktok.com/@dragonsden

Dragons’ den. (n.d.). www.cbc.ca. https://www.cbc.ca/dragonsden/

Dreher, N. (2019). Food from Nowhere: Complicating Cultural Food Colonialism to Understand Matcha as Superfood. Graduate Journal of Food Studies, 05(01). https://doi.org/10.21428/92775833.61bff69f

Halpert, M. (2024, October 15). Boba tea company apologises over Canada Dragon’s Den row.

Handley, L. (2024, December 9). From failed accountant to Marvel and Barbie star: Simu Liu shares how he got out of “rock bottom.” CNBC.

Heldke, L. (2003). Exotic Appetites: Ruminations of a Food Adventurer. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315822068

Hooks, B. (2015). Black looks: race and representation. Routledge.

Liu, S. [@simuliu]. (2024, October 12). some thoughts on boba/bobba lets be kind to each other! [Video]. TikTok. https://vt.tiktok.com/ZS6ko5xn9/

Liu, S. [@simuliu]. (n.d.). Actor • Author • UNICEF Canada Ambassador [TikTok profile]. TikTok. Retrieved December 20, 2024, from https://www.tiktok.com/@simuliu

Minhas, M. [@manjit.minhas]. (2024, October 13). Hi everyone Dragon Manjit here. Last week’s episode had a pitch from entrepreneurs about Bobba Tea that has sparked a [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/DBErM3SyOCx/

Quijano, A. (2007). COLONIALITY AND MODERNITY/RATIONALITY. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353

Raj, K. [@car.thicc]. (2024, October 14). Move over Bobba, Chye is here #bobba #sharktank #dragonsden #bobatea #boba #chai #chaitea #simu #simuliu #asiantiktok [Video]. TikTok. https://vt.tiktok.com/ZS6B8Huys/

Sand, J. (2005). A short history of MSG: good science, bad science, and taste cultures. Gastronomica the Journal of Food and Culture, 5(4), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2005.5.4.38

Zhang, J. G. (2019, November 5). How bubble tea became a complicated symbol of Asian-American identity. Eater.

Back to top