Persepolis: an autobiographical graphic novel

What are the advantages of writing your autobiography as a graphic novel, rather than a novel? This paper analyzes Satrapi's Persepolis as an autobiographical graphic novel.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Persepolis is an autobiographical comic series existing of four volumes published during the years 2000 up to 2003. Eventually bundled in one full graphic novel in 2003 and translated into a film in 2007.

Why did Marjane Satrapi choose this medium? this style and this form to tell her story? This study will look at the affordances given by the medium of graphic novels, it will analyze why what changed because of the form graphic novel instead of a more known autobiographical novel. Focusing on the style and choice of media, the use of characters, the use of reality effects and the fantasy of immediacy and intimacy.

Back to topPersepolis: an autobiography

The Complete Persepolis tells the story of Marjane Satrapi, also the actual name of the author, growing up in Iran. Satrapi’s goal is to show the world that Iranians are not the terrorists they are made out to be by the west. In the introduction to ‘The Complete Persepolis’ she writes: “Since then [Islamic revolution], this old and great civilization has been discussed mostly in connection with fundamentalism, fanaticism, and terrorism. As an Iranian who has lived more than half of my life in Iran, I know that this image is far from the truth. This is why writing Persepolis was so important to me, I believe that an entire nation should not be judged by the wrongdoings of a few extremists. I also don’t want those Iranians who lost their lives in prison defending freedom, who died in the war against Iraq, who suffered under various repressive regimes, or who were forced to leave their families and flee their homeland to be forgotten. One can forgive but one should never forget(Satrapi, 2003) .”

During the creation of The Complete Persepolis, Satrapi had been living in France for five years, where she currently still lives. In a video interview she says: ‘And Persepolis, I made the film in animation because the drawing is something abstract, so anybody can identify to a drawing. So that was really a reason why I wanted to make it in animation and nothing else.’ (I Am Film, 2013) Even though she is referring to the movie she also chose this strategy for her graphic novel.

In another interview the interviewer asks Satrapi: ‘And then how did the graphic novel turn into a movie?’ (Movie Web, 2010) at which Satrapi answered: “Well that was a mess, because I never wanted to do that, and I always thought that was a very bad idea, I still do. It’s not that when you are a good cartoonist you become a good moviemaker. And it is not that something that would work as a comic will work as a movie. Knowing that was very good, because I knew the danger of the project (Movie Web, 2010).” After which she explains that she made the movie because a good friend of her wanted to become a film maker and she would like to work with him.

In the video interview mentioned before she also says: “My basis come from painting, and then I made comic books because I wanted to make popular art. Because I didn’t want to make some painting and then go to some galleries and then some elite people would come and watch my paintings, and that would be it. I say, I can make something that is popular and not stupid. It is possible that you can make something that everybody can read, but is well made (I Am Film, 2013).”

All of this shows her thought process behind the decisions for form and style. In the interview with Movie Web, when she is asked why she wrote Persepolis she says: “The two times that I left Iran before in ’84 and ’94, I heard so many crazy thing about my Iran, you know? People were saying things, and I was like, this is not like this, that is not like that. And you know that is a truth, a reality that you see at a TV-channel. And I am not saying that it doesn’t exist, it does. But there are many other reality’s that you never see .. I will give you at least another view (Movie Web, 2010).”

The graphic novel ‘The Complete Persepolis’ was made carefully choosing form and style to reach a big audience and translate a different but existing truth. It was designed to be identifiable by as many different people. This study will analyze the affordances of the form ‘graohic novel’ for an autobiographical narrative using The Complete Persepolis.

Back to topChoice of media and style

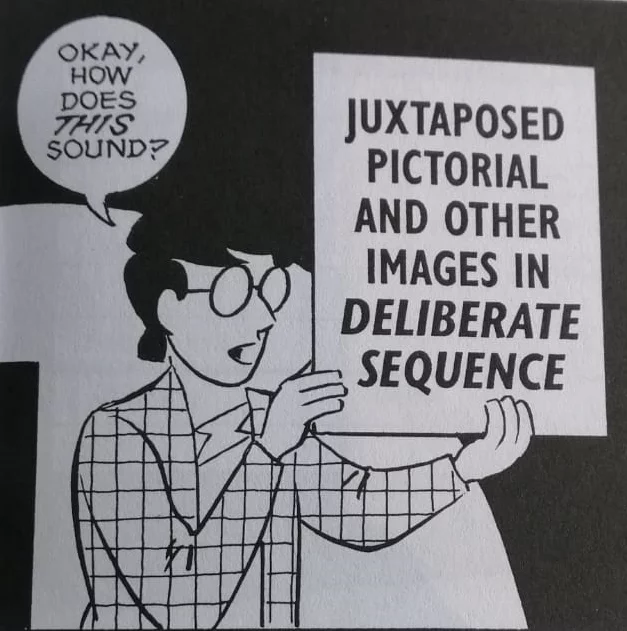

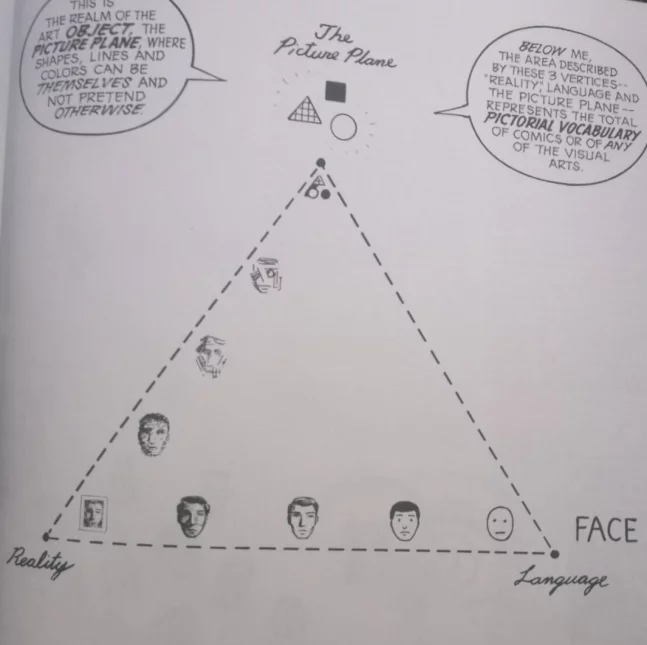

In 1993 Scott McCloud wrote a graphic novel about the art of comics and how to understand them ‘Understanding comics, the invisible art’. In this book he goes through the (rich) history of comics as well as the theories behind comics. He starts with his definition of a comic, which he takes different steps for to arrive at. Resulting on Page 9 in his definition of comics shown in the picture above. According to McCloud all comics can be placed on the ‘picture plane’, a triangular shape with the three dividing corners: reality, language and the picture plane. (McCloud, 1993)

His theory says that there is a clear decision and purpose behind the style chosen for a comic (or any art piece for that matter). On the bottom left we have reality, the beauty of nature, recreating rich beautiful places on earth. But the message of the picture is less important. In the right bottom we see Language, which is all about meaning, the landscapes and especially the characters are abstract but only the meaning of the image is important. Scott uses the example in the picture of the face, the word face being the most abstract ‘drawing’ or icon for the face. We are left with the picture plane in the top, not focusing on meaning or reality, the beauty of art, all about the aesthetics. (McCloud, 1993)

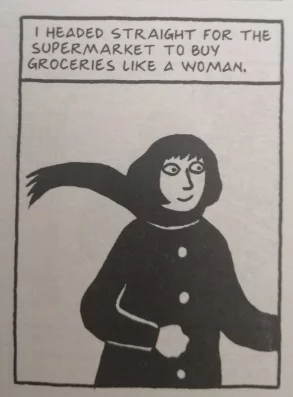

When we analyze the style Satrapi decided on for Persepolis we can clearly see that it is a very abstract style. The face of Marjane being ‘dumbed’ down to a circle and a few lines, hair and later on one mole. As Satrapi already said in the video interview de decision on style and media was a very important decision for her, she wanted as many people possible to be able to read her book and understand the meaning behind it and see the different truths that exist.

McCloud explained this phenomenon very well in his book, he says: ‘When you look at a cartoon … you see yourself’ (McCloud, 1993) He compares it to ‘looking from behind a mask’, during a conversation you always see the face of another person but you always look at yourself from behind your own face. Therefore, when we look at a realistically drawn face or a photograph we see another person, but when we see an abstract face in a cartoon we see a concept that we bring to live with our own minds. We see ourselves.

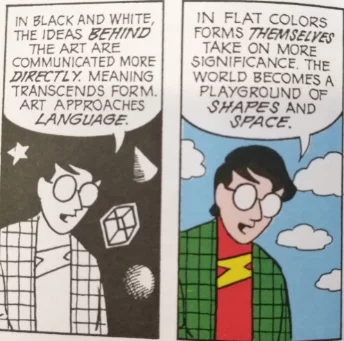

This is one of the very consciously made decisions by Satrapi that adds both to the purpose of the graphic novel as to the way it is received. Additionally the fact that she decided to keep the comics black and white caused for the idea’s behind the art to be ‘seen’, or important, instead of the shape, color and art itself. This again contributes to the idea that Satrapi’s Persepolis should be placed on the right, meaningful and iconic side of McCloud’s picture plane. (McCloud, 1993)

The importance of characters

In the autobiographical graphic novel ‘Persepolis’ the main character is Marjane. Satrapi her goal was to show people a different truth about the people in Iran than they had been witnessing on TV. She could have done this in multiple ways, she could have interviewed people and analyze their answers, she could have written a fictional novel with characters situated in Iran at the time, but she chose to write an autobiography. ‘Through protagonism, antagonism, and emotional growth, we acquire narrative pleasure and narrative comprehension.’ (Batty, Me and You and Everyone We Know: The Centrality of Character in Understanding Media Texts, 2014)

In2014 Craig Batty published a study: ‘Me and You and Everyone We Know: The Centrality of Character in Understanding Media, in which he claims that characters ‘populate’ a narrative, they create meaning, they guide you through the story and make the story credible. He also argues that the readers enjoy the narrative when they (try to) understand the narrative and its meaning, and meaning can only be achieved through the character(s).

Readers want to find out why something happened, why it is shared with them. They want to understand. "…we can understand the audience-character connection and how it develops through the structure of the text as pertaining to narrative pleasure: a mechanism by which audiences judge the success of a […] text, seeking to find plot points and dramatic junctures which adhere not only to their expectations, but their ability to understand the story told." (Batty & Waldebeck, 2008)

‘… all the traits of a fictional protagonist to draw in her audience: a complex backstory, a unique persona, a strong voice, and alarming actions.’ (Batty, Me and You and Everyone We Know: The Centrality of Character in Understanding Media Texts, 2014) Marjane has a complex backstory, growing up in a country of war and being descendant from former rulers. She is introduced to be very unique and different from her peers, wanting to become a prophet and conversing with god. She is never afraid to confront the authorities which often causes alarming actions even resulting on living on the streets for a certain while.

According to Craig Batty a narrative needs a character to guide the reader through the story, without a character there would not be meaning to the story. The reader needs the context of the experience of a character to understand what the story means. Not only the decisions for media and style have been used to converse the understanding of a different truth but also the form in which Satrapi wrote the graphic novel adheres to this goal. She could have written about how the situation in Iran is or was, and explain how there are many different people. However, Satrai decided to use herself, as character, and he life as thread that we follow through the story so that we as reader can understand the meaning of the story.

Back to topThe autobiographical pact

Comics are often seen as fictional superhero fantasy stories. Scott McCloud calls them the invisible art because they are often forgotten or not taken seriously. However, Marjane Satrapi made the decision to use this form to tell her story about growing up in a country taunted by war. As did Art Spiegelman when he wrote Maus (1991), another graphic novel about Spiegelman interviewing his father about his experiences during the second world war.

These are serious topics about terrible things that actually happened. Luckily there have been quite a lot of serious (autobiographical) graphic novels the last few decades, but how are they different from a novel? First of all as many have argued but first coined by Lejeune in 1975 in his ‘Le Pacte autobiographique’. An autobiographical narrative enforces a pact, or contract, with the reader. It explains to the reader that this is a true story lived by the author. Satrapi makes this very clear right at the beginning of her graphic novel.

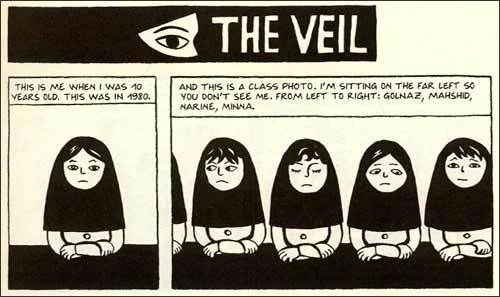

This picture has been analyzed a lot, including in ‘The Texture of Retracing in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis’ by Hillary Chute (2008) and in the TED talk by Micheal Chaney ‘How to read a graphic novel’ (2011). (Chaney, 2011) These two pictures combine both the contractualization of the connection between author and reader. She will give us a representation of who she was and the world around her, this is how she looked like back then.

Secondly it is an instruction on how to read the novel. In the first panel we see Marjane, in the second picture is a drawing of a school picture showing her peers but only Marjane’s left edge of her body. The text reads: ‘And this is a class photo. I’m sitting on the far left so you don’t see me. From left to right..’ However, we see Marjane very well to the far left, in the other frame. All the girls look almost all exactly the same, but we should look at Marjane differently. She is not part of a group. We should already understand: ‘Individuality despite seriality’ (Chaney, 2011)

Back to topConclusion

The decisions that Satrapi made before and during the creation of The Complete Persepolis have given her a lot of affordances that help readers identify with the characters, help readers identify with the story and most importantly it helps the reader understand the meaning of the story. In my opinion the graphic novel is an excellent form of autobiographical narratives and apart from a few famous graphic novels that have slipped through ‘the glass ceiling’ of the arts most of them are still not known or ignored. Autobiographical graphic novels are a good form of transferring a bigger or more conceptual truth or meaning to readers than just an autobiographical novel.

Back to topReferences

Batty, C. (2014). Me and You and Everyone We Know: The Centrality of Character in Understanding Media Texts. Real lives, celebrity stories: Narratives of ordinary and extraordinary people across media, 35-56.

Batty, C., & Waldebeck, Z. (2008). Writing for the screen: Creative and Critical Approaches. Palgrave Macmillan, 149.

Chaney, M. (2011, March 6). TEDxDartmouth 2011- Michael Chaney: How to Read a Graphic Novel - March 6, 2011. Opgeroepen op May 30, 2019, van YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qAyEbgSPi9w

Chute, H. (2008). The Texture of Retracing in Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis. The Feminist Press, 92-110.

I Am Film. (2013, November 11). Marjane Satrapi. Opgeroepen op May 30, 2019, van YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ttHRWxiYU50

McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Collins.

Movie Web. (2010, September 19). Persepolis - Exclusive: Marjane Satrapi. Opgeroepen op May 30, 2019, van YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v9onZpQix_w

Satrapi, M. (2003). The Complete Persepolis. New York: Pantheon Books.

Back to top