Do viral campaigns work? From Movember to #itsoktotalk

Viral challenges like the Ice Bucket Challenge or Movember have raised awareness and money for charity. We propose that a combination of seriousness and playfulness may be an important element of such campaigns.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

On this page

Most of us remember the worldwide famous Ice Bucket challenge when people poured ice-cold water on themselves. It serves as a conspicuous example of an online campaign which attracted attention of a huge number of people, here to the problem of ALS. We believe that the playful nature of this online initiative was the main reason for its immediate success and we will provide several other examples of fruitful internet activism with playful elements.

Back to topHashtag activism

Spending time behind a computer screen instead of real interpersonal communication has become a more habitual form of interaction for most of the people of the millennial generation. It allows us to voice our opinions without fear and to express our viewpoints without much effort.

These two aspects of social media are putting pressure on more primordial forms of activism — public speaking, protests, marching and strikes. Social media allows us to share a message that we find significant or eye-catching, and then forget about it, as we continue to scan our friends’ feeds. We continuously witness social justice messages, but we do not take the time to actually react on them. This form of action is commonly referred to as 'slacktivism' or 'hashtag activism'. And we have all taken part in it. There have been a great number of examples in the past years.

"We like likes, and social media could be a good first step to get involved, but it cannot stop there."

There are various views on the matter of slacktivism. Some people consider that slacktivism enables us to be lazy and cowardly, feeling good about ourselves and our little contribution. Amongst those criticizing hashtag activism is UNICEF Sweden, the first major international charity to come out and say that people who actually want hungry, sick children saved need to donate money and supplies — not just virtual support (Khazan, 2013). "We like likes, and social media could be a good first step to get involved, but it cannot stop there," said UNICEF Sweden Director of Communications Petra Hallebrant. "Likes don't save children's lives. We need money to buy vaccines for instance."

Nevertheless, others detect more positive features in this new form of activism. Even though the criticism is true, the positive sides should not be neglected. We support the positive viewpoint. Such online campaigns, first of all, help to attract attention of many people from different countries on important matters like male suicide or sick children, suffering women or incurable diseases. Also, due to its playful nature they easily engage people to participate, turning a serious initiative into something “fun”. Virality, after all, is a form of mass mobilization.

That playful nature is an element of some challenges that we believe is the key to success. In this paper we will propose a scale of ludicism, to indicate that there are levels of playfulness and seriousness a campaign can contain. Despite the criticism that slacktivism is passive, a playful element to a campaign can make people more engaged, showing the positive side of hashtag activism.

Back to topLudicism

The main reason why such activism appeals to people is its ludic nature. The term ludic (Huizinga, 2014) comes from the Latin ‘ludus’ (play, game, sport). The term reflects the general definition of ‘play’ as essentially ‘useless activity’ (Santayana, 1896) that serves no practical purpose, but is rather ‘intrinsically motivated’ for its own sake (Holbrook & Olney, 1995).

The role of ludicism in mass communication is becoming more important. It seems that playful elements in all kinds of activities have the capacity to shape new kinds of groups, often of a rarely seen size and scope. For the same serious purposes but with ludic elements in the acts, a campaign has more chances to go viral because people make friends while playing, because play enables them to show their ‘authentic’ self (Blommaert, 2017). This way, people can find the "similarities" which they share with each other. In a natural way, they will start sharing or repeating these activities on social media.

The reason why we think the challenges ... are effective in raising awareness or even money is because they are ludic.

Below we will list some examples of online and offline challenges that have raised awareness, and some amongst them have also raised money.The reason why we think the challenges described below are effective in raising awareness or even money is because they are ludic. We interpret ‘ludic’ here as play, but that play at the same time is very serious. Blommaert (2017) highlights some features of play from a list Huizinga (2014) put together. Some of the elements Blommaert features suit the challenges we will discuss here very well; they are a possible explanation of why the challenges are successful.

First of all, Huizinga mentions that play is a site of meaning-making, it is significant, but it is also a voluntary activity. Also, play is a serious activity that demands focus, intensity and skill. On top of that, it has an aspect of inevitable learning. This last aspect defines well why the challenges we will discuss can be effective in raising awareness. Since the challenges are ludic, an element of learning is involved. Therefore everyone who sees the challenge or participates in it inevitably learns something. That ‘something’ is likely to be the subject of the challenge. The main purpose of the initiative is not always the message behind it, but most likely the message will shine through and will be picked up and learned about. Without learning about the message, participating in a challenge consists of simply following the rules.

An example of activism that spread online, but happened offline, is the ‘Ice Bucket Challenge’. This challenge went viral in August 2014. The goal was to raise awareness and money for ALS, a lethal muscle disease. It started as a challenge to pour a bucket of cold water over your head to experience the feeling of ALS, and to donate to research funds for ALS. This later informally changed to being challenged to pour the water over your head, or giving something to the person challenging you. In 2014, $11,4 million was donated to the ALS Association, but it could have been more if the activity had not changed. It did however raise awareness, as people got to know about the disease.

An interesting trait of this challenge and others is that there is one element of play as described by Huizinga (2014) that does not at all fit the challenges: Huizinga describes that “play is relatively unregulated and unconstrained by established rules and forms of control”. While ludicism already has a serious component, rules add another aspect of seriousness. Challenges may therefore be seen as less ludic. We still believe they are, even those that are far more serious.

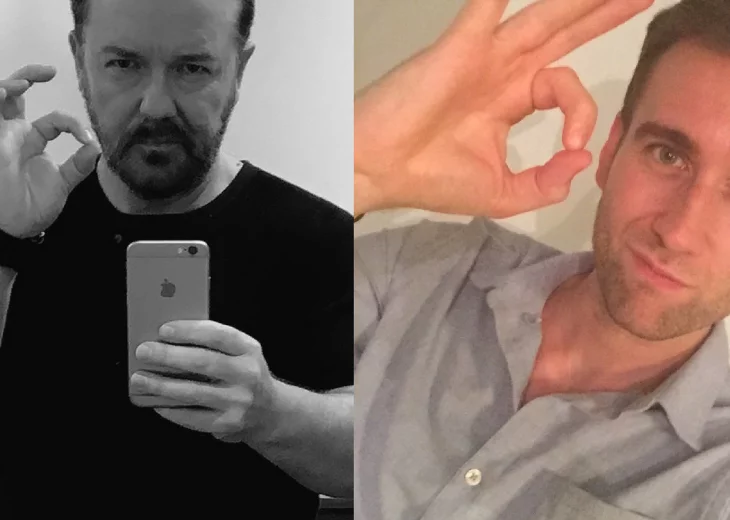

The Irish rugby player Luke Ambler lost his brother-in-law to suicide. He posted a selfie in the summer of 2016 with the description “41 percent of men who contemplated suicide felt they couldn’t talk about their feelings”, and he designed the hashtag #ITSOKAYTOTALK. This hashtag became a challenge: people were asked to tag five friends to post a selfie accompanied by the text and hashtag that Ambler introduced. The message and topic of this campaign are very serious, but it has a playful element: the challenge itself. The selfie is meant to draw attention, after which people will read the text and be informed about the matter. We think that this challenge is still ludic in the way it raises attention. Because the Ice Bucket Challenge and #ITSOKAYTOTALK differ very much in how much they are playful and serious, we would like to propose a theory that there is a scale of ludicism.

Back to topThe message and topic of this campaign are very serious, but it has a playful element: the challenge itself.

A scale of ludicism

The scale of ludicism that we propose is based on the assumption that some ludic things contain more of the playful elements, and other things are more serious in nature. The following example is a more serious challenge: The Great Gorilla Run . The Great Gorilla Run is an annual eight-kilometer run through London. The goal of the event is to raise money for saving gorillas in the wild. In order to participate, people have to pay money. The entrance fee is £30, but participants are asked to raise as much money as possible. The cause for which they run is serious in nature, which makes the run serious. However, the participants receive a gorilla suit which they have to wear during the run. The running itself and the gorilla suit are the playful elements of this run. On the scale of ludicism, both the Great Gorilla Run and #ITSOKAYTOTALK are more serious in nature, but they differ in the degree in which they contain playful elements. While #ITSOKAYTOTALK contains little playfulness, the Great Gorilla Run is very playful with all the people running in gorilla suits.

The other end of the ludic scale can be exemplified with a few other challenges. These challenges have a playful nature, with elements of seriousness. They differ from the two formerly mentioned examples in the fact that the essential core of the challenge is playful rather than very serious. The Ice Bucket Challenge lies somewhere in between: at first it was more serious, but later became a playful challenge with a lesser focus on ALS and donating to the ALS Association. This shift on the scale might have influenced the campaign going from raising money to raising awareness.

We have two examples of challenges that are playful with serious elements. The first one is Movember. Males are challenged to grow a moustache in the month of November every year. The goal behind this is to raise awareness for men’s health issues and to raise money for charities that are associated with male cancers and other diseases. This challenge happens mostly offline, but every year many pictures of the progress of growing the moustache are shared online.

The second challenge is an online initiative, the ‘No Makeup Selfie’. Celebrities would share a selfie in which they were not wearing any makeup. The campaign has the goal of raising awareness (and money) for Cancer Awareness. The challenge has been shared through the hashtag #nomakeupselfie, and has also been done by women who are not celebrities. Dockterman (2014) wrote an article criticizing the activism, saying how she does not understand what the relationship between wearing no makeup and cancer awareness exactly is. This also was missed by many participants of the challenge, as many of the #NoMakeupSelfie photos did not mention cancer awareness. Dockterman therefore proposed to just donate to the American Cancer Society. In this challenge, the basis is playful, especially in the photos that do not mention cancer awareness. Many people just participate in the challenge by posting a selfie.

Back to topEven if the offline effects are limited, online activism can generate large communities in which knowledge, awareness, caring and solidarity circulate, and such effects should not be dismissed as irrelevant.

Conclusion

To conclude, playfulness is an element we found present in several successful viral campaigns. The combination of seriousness and playfulness, i.e. ludicism might be the recipe for the success in our examples. If you take either one of them away, the meaning behind it is lost or it might appeal to fewer people. We do not intend to rank examples on a particular scale, but rather to propose that there is a scale in which ludic activism may occur. The division between seriousness and playfulness is not always clear-cut, true. Yet, we propose this scale in order to define why campaigns might have been successful, and to explain the degree of ludicism they contain. For example, the hashtag #ITSOKAYTOTALK was very serious in nature with a little element of playfulness, Movember is mostly playful with a serious element, and the Ice Bucket Challenge lies somewhere in between.

Despite the severe criticism towards online campaigns and initiatives, our examples proved to be educational and beneficial attracting all sorts of audiences to the posed problem or disease. The examples battle the criticism on slacktivism, and they show how online activism can be successful and helpful. Even if the offline effects (such as fundraising) are limited, online activism can generate large communities in which knowledge, awareness, caring and solidarity circulate, and such effects should not be dismissed as irrelevant.

Back to top

References

Blommaert, J. (2017). Ludic membership and orthopractic mobilization: On slacktivism and all that. Retrieved on November 1st, 2017 from https://alternative-democracy-research.org/2017/10/09/ludic-membership-…

Dockterman, E. (2014, March 27). #NoMakeupSelfie Brings Out the Worst of the Internet for a Good Cause. Retrieved on November 1, 2017, from http://time.com/40506/nomakeupselfie-brings-out-the-worst-of-the-intern…

Holbrook, M. B., & Olney, T. J. (1995). Romanticism and wanderlust: An effect of personality on consumer preferences. Psychology & Marketing, 12(3), 207-222.

Huizinga, J. (2014 [1950]) Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. New York: Roy Publishers.

Khazan, O. (2013, April 30). Unicef tells slacktivists: Give money, not Facebook likes, The Atlantic, retrieved from theatlantic.com

Santayana, G. (1896). The sense of beauty: Being the outlines of aesthetic theory. C. Scribner's sons.