Life is Sublime: Exploring the Power of Choice-based Narratives in Discussions on Anthropocene

This article explores debates surrounding the Anthropocene by analyzing the 2015 choice-based game Life is Strange. It examines how the game employs sublime visuals, a non-linear narrative, and a focus on grief to create a thought-provoking experience for players, offering commentary on the consequences of human impact on nature.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

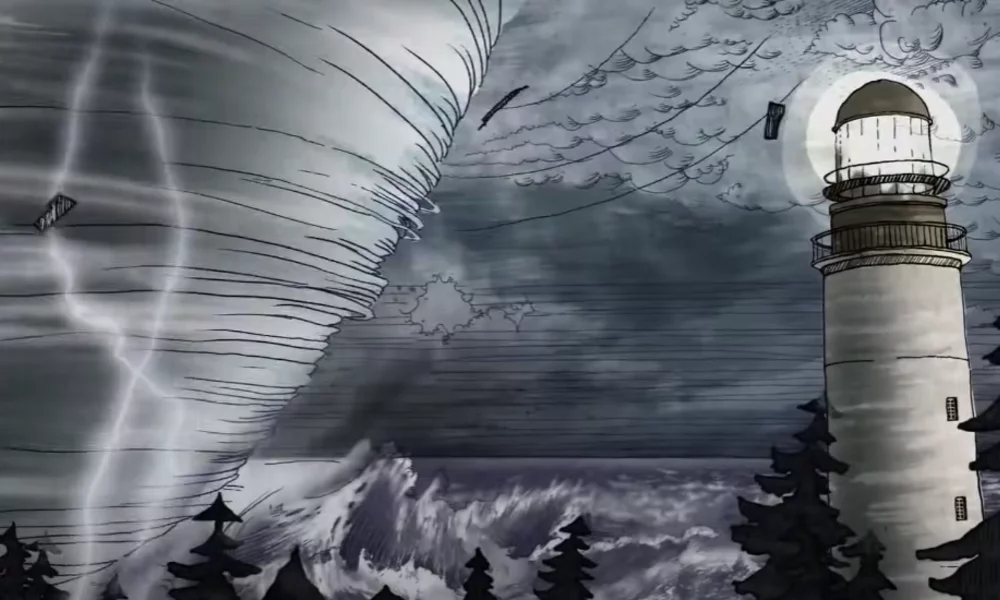

You open your eyes to see a lighthouse, the sky is grey and the wind is knocking you off your feet as you look out onto the coastline of your hometown about to be eradicated by a massive tornado. You reach out a hand, and the next thing you know, you are in your high school bathroom, watching your best friend, who you have not seen in five years, get shot. Which reality do you choose?

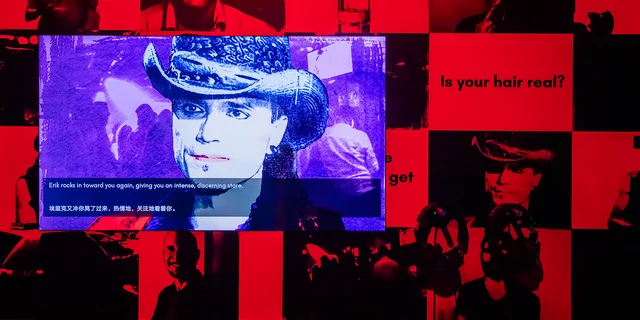

This is the opening scene of a 2015 episodic choice-based game Life is Strange (LIS), developed by French Dontnod Entertainment and published by a Japanese entertainment conglomerate, Square Enix. It became the first instalment in a series of games that explore experiences of adolescence through the speculative fiction narrative of supernatural powers. The earlier scene introduces the player to the game’s protagonist, a high-school student in a unique Photography program named Max, whose ability to manipulate time triggers once she sees her childhood friend, Chloe, die (Figure 1). From this point on, the player makes choices on behalf of Max as she navigates her power, relationships and town’s mysteries as a natural disaster, caused by her countless rewinding of time, approaches.

According to the game's developers, LIS is a realistic story that uses the supernatural to explore the complex feelings and relationships of the characters (Lemne, 2015). However, these metaphors serve as a lens to examine the larger relationship between nature and humanity, as there are visual and narrative consequences to which options the player chooses in their gameplay. In this article, I examine the sublime of Life is Strange’s metaphors, its ‘butterfly effect’ choice-based narrative, and how these elements contribute to the ongoing debate about human environmental intervention. Thus, I aim to determine how Life is Strange contributes to the broader discussion of the Anthropocene in its storytelling through visual, narrative and relationship choices.

Back to topLife is Disastrous: The Sublime of Visual Metaphors

Philosophers have explored the sublime as a complex and powerful emotion for centuries, yet the modern sublime is based on key contributions from Edmund Burke (1757/1968) and Immanuel Kant (1764). Edmund Burke, an Irish philosopher, statesman, and political theorist, in his work A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757/1968), defines the sublime as an intense, almost overwhelming emotional response to vast, powerful, and sometimes terrifying experiences. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), a German philosopher, further expanded on Burke’s definition in Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime (1764/2003) and, later, in Critique of Judgment (1790/2024). While Burke's sublime is a visceral, physical reaction, Kant’s sublime emphasises the conflict between sensory experience and reason, where nature’s complexity overwhelms the mind (Shaw, 2017).

These interpretations highlight the overwhelming nature of the sublime, an experience that evokes a mixture of sensations. While Burke and Kant were instrumental in shaping the discourse on the sublime, the concept extends beyond their theories. In the Romantic sublime, the human is confronted with the power of nature, like in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, and further contemporary reinterpretations of the sublime in philosophy, literature and art (Shaw, 2017). Romantic sublime is also where the semiotics of the sublime became firmly established, with some characteristic visuals and symbolism. Vast landscapes are depicted as antithesis to minuscule solitary human figures as a dramatic contrast that represents the complex feelings sublime evokes. In LIS, typical visuals of the Romantic sublime establish it as part of the genre. Akin to the previously mentioned Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, Max stands small in the foreground while a destructive storm fully takes up the main frame (Figure 2). However, these visuals stand out in the context not only as a nod to the Romantic sublime, but also as commentary on Anthropocene.

LIS uses the sublime as one of its central themes to explore the complexity of humans and nature. It engages with the Anthropocene epoch, a proposed current geological timeframe characterised by the effects of human activity on nature (Edwards, 2015). Despite being rejected as a proposed name for the current geological epoch, at the core of the Anthropocene is a very important social idea (Working Group on the ‘Anthropocene’, 2024). The Anthropocene is marked by significant environmental transformations resulting from industrialisation, deforestation, pollution, and climate change, leading to rising global temperatures, extreme weather events, and declining biodiversity. It challenges the traditional separation between humans and nature, present in some readings of the sublime, as it establishes the interdependence of human activity and nature. In LIS, this epochal shift is represented through the storm and environmental anomalies, which serve as both narrative and visual metaphors for the unintended consequences of human intervention. By incorporating the Anthropocene into its storytelling, the game not only engages with ecological anxieties but also prompts reflection on the ethical and existential dilemmas surrounding human agency in shaping the planet's future.

The storm’s ominous presence is introduced early in Episode 1, with Max’s nightmare setting the stage for the tension between her newfound powers and the looming disaster; she walks up the hill in the storm as falling boulders and ripped-out trees make her rewind countless times to avoid getting hit. The scene of the vision reveals that the storm is only four days away from happening in real-time, which prompts Max to reveal the truth about her powers to Chloe as the snow starts falling on a warm early October day.

While the storm poses impending doom throughout the game, there is a certain aesthetic characteristic of the portrayal of an approaching disaster. As the player roams the in-game world, they encounter multiple anomalies, signals of the disaster. As threatening as they are, the framing makes them look breathtaking, and in some instances, the player is prompted to take pictures of those anomalies as Max (Figure 3). The rapidly changing weather, mirroring Max’s powers, symbolises humanity’s increasing involvement in nature’s trajectory, while the storm’s growing intensity suggests the disastrous consequences of this intervention. Simultaneously, they progress beyond Max’s influence, as she cannot fix these consequences by rewinding; on the contrary, her power might worsen the destruction. When it snows in the first episode, Chloe is confused and asks Max how this can happen in 20-degree weather. Max’s answer is: “Climate change. Or a storm is coming” (Dontnod, 2015). The game combines the supernatural with the real, rapidly changing weather, dying animals and other ‘anomalies’ are becoming daily lives for us. The only difference is that the LIS world goes through it in a week while the real world has been facing this for decades.

The aesthetics of destruction in LIS present a sublime picture, which at first glance can align with the awe and terror of Burke, the tension between reasoning and the overwhelming nature of Kant, and even the visual opposition, man vs nature, of the Romantic sublime. The diversion from photorealism in the game’s art style, the use of a painted effect, further impacts the sublime atmosphere throughout the scenes, resembling Romantic period paintings in both technique and framing of subjects. However, it presents a more contemporary view of the direct human impact on nature and the corresponding impact of nature on humans, connecting the visual progression of destruction to the Anthropocene epoch. The storm, through its powerful visuals and the accompanying scenic anomalies throughout the game, acts as a metaphoric representation of causality related to human intervention. The sublime of the storm, thus, goes beyond a visual representation of awe and terror, of nature over humans, but also as a catalyst for powerful commentary.

The foundational theories of the sublime inspired many pieces that focus on more niche branches of the experience, especially in the postmodern world as the debates on the Anthropocene started becoming prominent. One of such branches is the apocalyptic sublime. Life is Strange embodies the apocalyptic sublime in its narrative of a destructive storm, as shown by the visual flashbacks that Max regularly experiences throughout the game and the scenes of anomalous weather. However, the apocalyptic sublime is also heavily represented throughout the game's narrative.

Back to topLife is Uncertain: Apocalyptic Sublime through Player’s Choice

Gunn and Beard (2000) proposed that the apocalyptic sublime has two standout characteristics that differentiate it from the previously identified ‘traditional’ apocalyptic narratives. Those are its reliance on nonlinear progression and the destabilisation of subjectivity, which replace the typical notion of an ‘imminent’ apocalypse with a ‘persistent’ one (Gunn & Beard, 2000). The apocalyptic sublime is expanded upon by Salmose (2018), targeting narratives which combine fictional apocalypse with references to real references to climate change and the consequences of the Anthropocene. The apocalyptic sublime is then divided into two categories: action, focusing on the spectacle and immediate emotional effect, and poetic, focusing on metaphoric narrative, atmospheric and introspective (Salmose, 2018). While both are present in LIS to a certain degree, its narrative is overwhelmingly leaning towards the poetic apocalyptical sublime. The interplay between player choice and Max's time-rewind mechanic in LIS creates a unique experience of the apocalyptic sublime, emphasising the tension between human agency and the overwhelming implications of the Anthropocene.

‘Life is Strange is a story based game that features player choice, the consequences of all your in game actions and decisions will impact the past, present and future. Choose wisely…’ - this disclaimer appears at the start of the game’s first episode (Dontnod, 2015). It is continuously reinforced through a butterfly icon in the corner of the screen throughout gameplay (Figure 4). The player’s choices impact the story's direction: the availability of some future choices, dialogue options and cutscenes. However, since Max has the power to manipulate time, these choices can be changed (although the amount she can go back at once is limited). This is not typical for games with similar mechanics, like Telltale’s The Walking Dead (2012) or any of Quantic Dream’s interactive film games, where the player has to stick to all first choices unless they replay the game/scene entirely.

The game’s divergence from the conventions of the choice-based game genre is part of its statement on agency and morality. This builds a metaphoric base for the larger debate of human intervention in nature by providing the exact nonlinear and non-subjective experience of the apocalyptic sublime, as Gunn and Beard (2000) outlined. With each rewind, the player confronts each event from different points of view as they see the outcomes of each choice and each persona Max can take on. These choices range from watering a plant to stealing from the handicap fund to help pay off Chloe’s debt. This, in turn, creates a sense of uncertainty in one’s identity, making the player question each of their decisions. After all, their struggle of choice is mirrored in Max, who knows how her power can benefit her. Low (2020), in her analysis of players’ choice in LIS, however, argues that the time-revision mechanic is more morally engaging for players despite their ability to revise their choices by rewinding. The players are prompted to observe the consequences of each action and change their choices to appeal to their moral judgment. They are given the option to do better if they decide to, which simultaneously builds attachment as they spend extra time engaging with the narrative

The constant revisiting of the past, amplified by the game's focus on emotional consequences, directly embodies Salmose's (2018) poetic apocalyptic sublime. While the player interacts with the story, building relationships, making complex decisions and rewinding for the best outcome, they are presented with an event they cannot change however they try to - the looming storm. No matter how much Max intervenes, it is all futile in the face of a storm destroying the whole town. Overall, the game uses its narrative to create a sense of tension between agency and futility; the revision is taxing while the storm remains unavoidable. This positions LIS as a powerful exploration of the anxieties and inherent ethical dilemmas in navigating the Anthropocene. The more Max tries to control time, the more she faces her limitations in controlling the natural world.

Amid the storm and moral choices, LIS’ narrative focuses on complex relationships, particularly between Max and Chloe. It highlights the emotional toll ecological crises take on humanity through the difficult decisions Max has to make for the town and her best friend in the face of a disaster. The narrative reflects the environmental crisis, where personal choices mirror global consequences, highlighting the moral dilemmas of the Anthropocene.

Back to topLife is Mournful: The Choice of Sacrifice and The Grieving of Self

The only choice throughout LIS’ four first episodes that the player has no say in is saving Chloe. The day that Max discovers her powers in the bathroom when Chloe gets shot, one cannot simply decide to let her die - Chloe survives with Max’s help. Further in the game, Max saves Chloe from another bullet, from a train, and even from an alternate timeline where Chloe is dying from chronic illness complications. Saving Chloe is a constant akin to the looming storm, and both happen no matter the players’ choices. Ultimately, however, Max has to choose between these two constants as her final decision at the end of episode five. Sacrifice Chloe or let the storm destroy the town. LIS engages in the discussion of Anthropocene, as the final choice connects personal loss with themes of grief in ecological disaster.

The player is introduced to the town during five episodes, and simultaneously to Chloe. As already established, the choice mechanic creates an attachment to both. Once immersed, deciding between the two becomes not just hard morally, as it creates a sort of a trolley problem, but also emotionally, as the player has been acting to save both throughout their entire gameplay. No matter what is chosen, Max experiences severe grief, but so does the player. With this, the game highlights an overlooked dimension of the discussions on Anthropocene, the grief humanity faces alongside climate change - the grief of the modern self (Head, 2016).

According to Head (2016), dealing with the mentally taxing consequences of human involvement in nature begins with giving up the idealistic view of a stable future, where everything will fall into place naturally, i.e. grieving the modern self. Max confronts that in a literal sense, she either needs to accept that Chloe was destined to die from the start or face the disaster caused by her intervention. Grief in LIS is a constant companion for the player, as the game emphasises the importance of facing it; each time they see Chloe near death, or witness the storm nightmare. This creates a powerful metaphor that weaves through the entire narrative, as the personal loss of loved ones mirrors the more abstract loss of an ideal future in the context of the Anthropocene. The narrative simultaneously mirrors what is known as climate grief, a term used to describe the impact climate-change-related loss has had on the mental health of many people (Cunsolo & Ellis, 2018).

As argued by Head (2016), and further by Cunsolo and Ellis (2018), there is an important message in LIS as humanity faces more and more similar natural disasters in reality, as grieving is the first step in navigating the emotional distress of climate change, healing and coming together to face the new future. By allowing players to repeatedly confront and revise their decisions, the game creates a personal and emotionally resonant experience of grief, making the abstract concept of environmental loss feel immediate and tangible. It makes the player simply take the first step in grieving the modern self by playing through a metaphor-packed, emotionally involved narrative.

Back to topLife is… Hopeful? The Impact of Sublime, Agency and Grief in Life is Strange

Life is Strange is a project that goes far beyond being a typical coming-of-age story, not just with its supernatural twist but with the crucial commentary it provides in contemporary debates on the Anthropocene. The game establishes itself as a sublime piece through visuals that craft an immersive atmosphere of awe and terror connected to natural disasters caused by direct human involvement. Further, its mechanic of choice engages in the modern debates about agency and futility in the face of natural powers, involving the player emotionally. In the end, LIS poses a question to all of us: What are we willing to sacrifice to protect our world? The game offers no easy answers, but it reminds us that even in the face of inevitable loss, we have the power to choose hope and action over despair.

Back to top

References

Burke, E. (1968). A philosophical enquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful (J. T. Boulton, Ed.). University of Notre Dame Press. (Original work published 1757)

Cunsolo, A., & Ellis, N. R. (2018). Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nature Climate Change, 8(4), 275-281.

Dontnod (Developer). (2015). Life is Strange.

Edwards, L. (2015). What is the anthropocene? Eos, 95.

Gunn, J., & Beard, D. E. (2000). On the apocalyptic sublime. Southern Communication Journal, 65(4), 269–286.

Head, L. (2016). Grief will be our companion. In Hope and Grief in the Anthropocene (pp. 21–37). Routledge.

Kant, I. (2003). Observations on the feeling of the beautiful and sublime (J. T. Golthwalt, Trans.). California University Press. (Original work published 1764)

Kant, I. (2024). Critique of judgment (Vol. 10). Minerva Heritage Press. (Original work published 1790)

Lemne, B. (2015, January 26). Life is Strange - "Supernatural things merely metaphors". Gamereactor UK.

Low, C. (2020). Moral Engagement and Time-Travel in Life is Strange. Digital Patmos.

Salmose, N. (2018). The Apocalyptic Sublime: Anthropocene Representation and environmental agency in Hollywood Action‐Adventure Cli‐Fi Films. The Journal of Popular Culture, 51(6), 1415–1433.

Shaw, P. (2017). Introduction. In The Sublime.

Working Group on the ‘Anthropocene'. (2024). Joint statement by the IUGS and ICS on the vote by the ICS Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy. Retrieved February 13, 2025.