If Jeff Bezos doesn't eat the Mona Lisa, who else will?

What would it mean if Jeff Bezos would buy and eat the Mona Lisa? This article demonstrates how a seemingly meaningless petition on change.org conjures various connections between contemporary manifestations of technologically driven nihilism and an upcoming battle between technocapitalism and intangible sociocultural values.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

As mentioned in a recent article about Reddit's Mona Lisa Clan, Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa is one of the most popular paintings ever created. Though popularity initially has positive connotations, there is also a darker side to being seen and loved by many. Often, popularity is accompanied by public scrutiny and criticism, sometimes even resentment. In the case of the Mona Lisa, there's even a word to describe the experience of disliking the popular Renaissance painting: Jocondoclastie. This term combines the French name of the painting — La Joconde — with the concept of 'Iconoclasm', which refers to the idea that icons and other visual artifacts should be destroyed. As such, the concept of Jocondoclastie refers to the desire to damage or destroy the Mona Lisa.

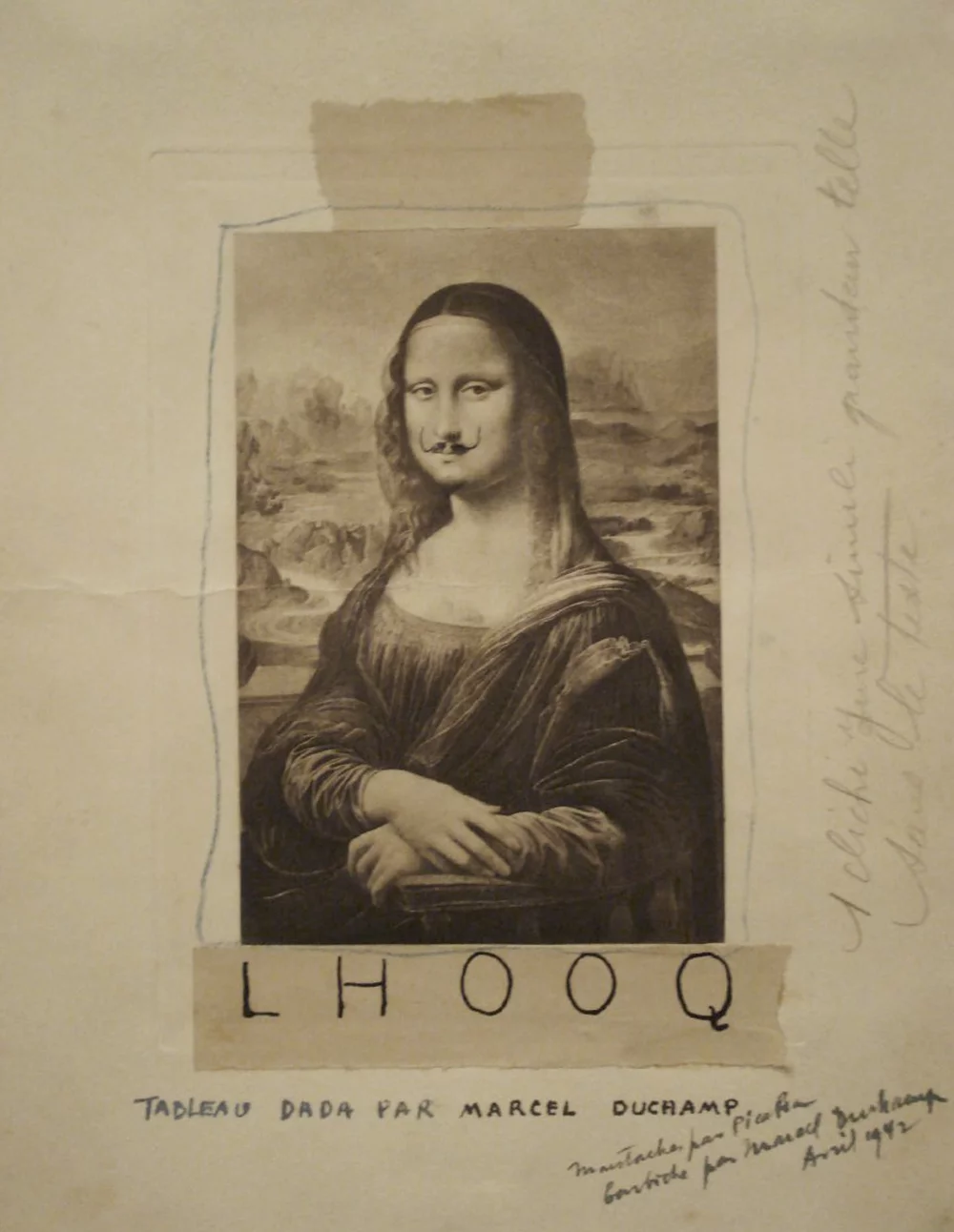

The term Jocondoclastie was introduced by the French hydrologist Jean Margat (Bizarre, 2009), who deformed visual representations of the Mona Lisa in accordance with the French painter and sculptor Marcel Duchamp's artwork L.H.O.O.Q. (see Figure 1). Following this example, jocondoclastic actions can entail ironic, derisive and contemptuous (mis)appropriations of the painting. More recently, the notion was also used to interpret various historic attempts to damage the Mona Lisa (Tolstoï, 2024), as well as the painting's theft from the Louvre in 1911. Judging from the broad applicability of the term, it seems reasonable to argue that some memefications of the Mona Lisa can also be understood as acts of jocondoclastism, just like other digital and popular culture practices that aim to disfigure the artwork. One example of the latter can be found in the change.org petition titled We want Jeff Bezos to buy and eat the Mona Lisa. Inspired by the persuasion that eating the Mona Lisa would be an extreme form of jocondoclasticism, this article analyzes the content of the petition and two categories of responses to the petition — (1) 'reasons for signing' that were added during the last twelve months, and (2) the first section of the most upvoted Reddit discussion about the petition — to gain insight into the relationship between Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos and the concept of Jocondoclastie.

A meeting between two icons

The change.org petition We want Jeff Bezos to buy and eat the Mona Lisa was published on January 1, 2020 by an account named 'Kane Powell'. Its description is rather short: "Nobody has eaten the mona lisa and we feel jeff bezos needs to take a stand and make this happen." Who 'we' is, remains unclear. The other main characters, however, are abundantly familiar. The Mona Lisa is "one of the best known images in Western culture" (Zöllner, 1993) and Jeff Bezos is the founder and CEO of Amazon, a company that belongs to 'Big Tech' — a group of internationally dominant technology corporations. Bezos is also known for being one of the world's richest individuals, for founding the space company Blue Origin, and for appropriating popular culture products like parts of Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. Despite not being mentioned in its description, there is another actor that plays a part in the petition: the online forum Reddit. In fact, Reddit is the first actor that is targeted as the intended executor of the petition's demand. Bezos is the second. Why this is the case, is not specified. Clearly, Reddit has no control over the Mona Lisa, nor over Bezos.

Nobody has eaten the mona lisa and we feel jeff bezos needs to take a stand and make this happen.

From a purely material perspective, it is difficult to imagine how Bezos and da Vinci's Mona Lisa could be more different. The Mona Lisa is a more than five hundred year old poplar wood panel covered with oil paint, that is now hanging in the Salle des États in the Louvre. Bezos is a white, middle aged man, who moves between multiple homes, but mainly resides in Seattle (Chen, 2024). The Mona Lisa has not left Paris since 1973, and will probably remain there, as transporting the painting poses significant risks, and its surface and structure increasingly crack and craze (Neuendorf, 2018). Bezos, on the other hand, "isn't close to death", and is both willing and able to 'leave' for his own benefit (Freedom Foundation, 2023). From socio-cultural and economic perspectives, however, both dominate their fields — be it the international art world or global tech industry —, and their 'net value' is eye-wateringly high. Symbollically, their positions might be comparable. They are both icons within their concerning spheres, and a 'final showdown' between the two might thus easily spark people's imagination and enthusiasm.

Back to topJeff Bezos should "gobble da lisa"

In the summer of 2024, the change.org petition had received well over 19,000 signatures. People who sign the petition are presented with an optional field that allows them to finish the sentence "I'm signing the petition because...". Many of the most recent responses to these words are relatively brief and simplistic, noting for instance that "why not?" and "This is very important to me personally" (see Figure 2). Responses like these highlight the type of irony and nihilism that increasingly characterizes digital culture.

"Technologies both enable and expand our nihilistic tendencies, allowing us to evade the burdens of consciousness, of decision-making, of powerlessness, of individuality, and of accountability"

Though the concept of 'nihilism' is much older, contemporary manifestations of nihilism can be connected to recent technological developments. This connection is nicely described by Gertz: "Technologies both enable and expand our nihilistic tendencies, allowing us to evade the burdens of consciousness, of decision-making, of powerlessness, of individuality, and of accountability" (Gertz, 2024, p. 10) According to Gertz, we can differentiate between two types of nihilism: passive nihilism and active nihilism. Passive nihilism focuses on "destruction for the sake of destruction" (Gertz, 2024, p. 10), whereas active nihilism engages with "destruction for the sake of creation". (Gertz, 2024, p. 10) The change.org petition is clearly of the first type. Having Bezos eat the Mona Lisa would be a largely meaningless, temporary spectacle — assuming people would be allowed to witness it. Though briefly exciting, it would ultimately be transient like many other absurdist, post-digital experiences. After the Mona Lisa's ultimate destruction, attention would inevitably need to be directed to something bigger and even more ridiculous to destroy. The Statue of Liberty, perhaps?

Other recent responses are longer and appear to incorporate political concepts. Participants argue: "Let's stand together and face the problems of society! Now we must make a tasty painting be gobbled up by a bald billionaire..." and "The future of the Earth depends on edible artwork. The Mona Lisa has been adored religiously for centuries. Now it's time to feed the masses." Both responses incorporate the observation that global society is in serious trouble. One of them mentions the political practice of 'making a stand', just like the description of the change.org petition: "jeff bezos needs to take a stand". The other refers to the notion of 'feeding the masses', which indexes 'hunger' and 'poverty' in relation to the political category of 'the masses'. In this sense, this particular proposal of Jocondoclastie appears to be framed in relation to a class struggle over resources. In this struggle, one of the most valuable objects on earth is juxtaposed against one of the most basic human needs — food. The idea of destructing the Mona Lisa to "feed" the masses both highlights massive societal inequality, as well as the improbable wish to resolve these inequalities through drastic, symbolic measures.

"Let's stand together and face the problems of society! Now we must make a tasty painting be gobbled up by a bald billionaire..."

In the context of the petition, 'the masses' could be interpreted as "individuals who live on the periphery of all social and political involvements" or as the "detritus of all social strata which have lost their former social identity and emotional bearings as a result of abrupt political, geopolitical and economic dislocation" (Baehr, 2007, p. 12). The latter description would align with the previously mentioned description of nihilism. People who are inundated with a endless stream of digital content, wicked problems, rising inequality, and no obvious methods to solve their issues, could easily feel 'dislocated' and emotionally detached. 'Everything' — all of the content, superficial opportunities and societal developments — is simultaneously 'too much' and 'not enough', as the combination of all of these circumstances renders profound connections and societal securities ever more unlikely.

Whether the two responders have any expectations of actual political change, is thus highly questionable. Through their use of irony, both responses signal the responders' mocking attitudes. Clearly, the future of the earth does not depend on edible artworks, there is no such thing as a "tasty painting" — and even if there is, the Mona Lisa does not classify as one —, and 'gobbling' a painting would not correspond to 'making a stand'. By ironizing the act of making a political stand, the entire idea of meaningful political action is undermined. If people say they want to "stand together" to "face the problems of society", they might just as well be joking. Following from this observation, we can argue that the responders are not regarding the disillusioned masses from the outside. They experience them from within, as even the notions of worldwide peril and taking control over the future are easily ridiculed, just like the activist potential of the platform on which the petition was launched.

Back to topIt's not just technology, it's also contemporary capitalism

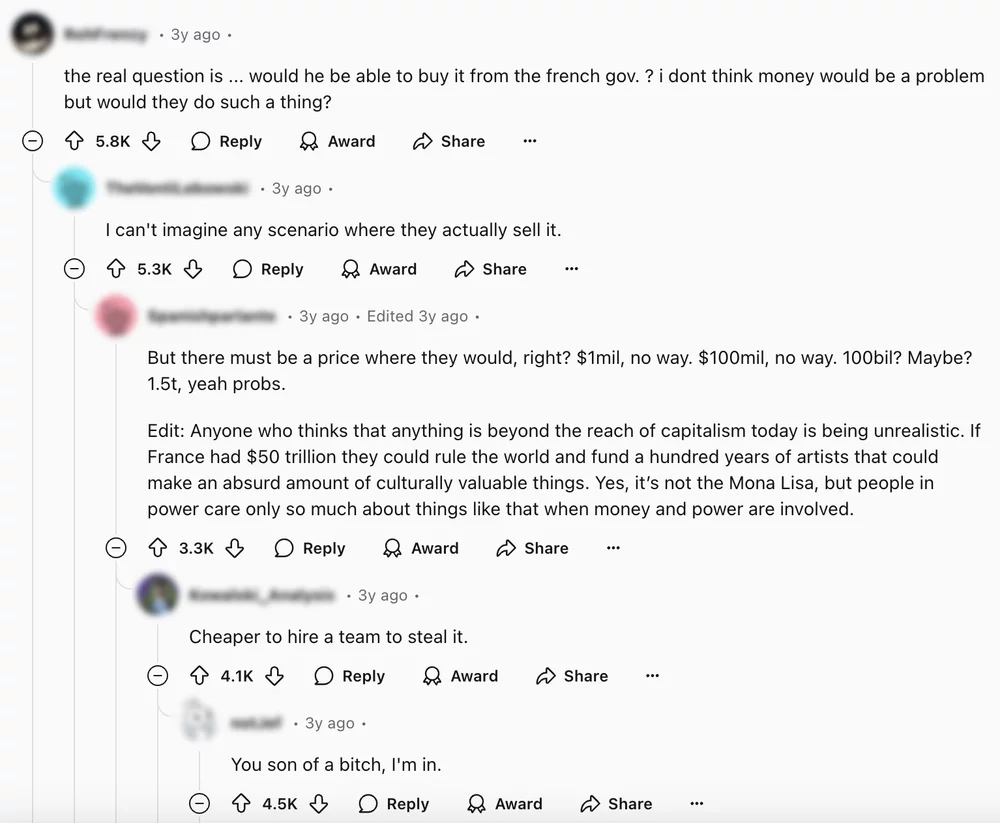

The Reddit discussion that was analysed for the purpose of this article, shows a slightly different picture, as some of the responses engage with the practical dimension of buying and eating the Mona Lisa (see Figure 3) rather than merely expressing ironic agreement or disagreement with the objective of the petition. One of the Redditors asks if Bezos would "be able to buy it [the Mona Lisa - Ed.] from the french gov. ?". The most upvoted answer to this question argues: "I can't imagine any scenario where they actually sell it." Many other responses, however, disagree. This perspective is nicely summarised in the notion that "Anyone who thinks that anything is beyond the reach of capitalism today is being unrealistic" — a sentence that is part of a comment that also received many upvotes.

The disagreement between these two streams of comments — being either utterly convinced that the Mona Lisa will never be sold, or arguing that money can ultimately buy anything — can be linked to the earlier mentioned idea that Bezos and the Mona Lisa are icons within their concerning spheres. Taking this idea one step further, we might argue that the idea of Bezos buying and eating the Mona Lisa constitutes a more abstract confrontation: A confrontation between post-digital capitalism and the intangible sociocultural values that dictate "meaning" and "social significance" (Byrne, 2008) within the cultural dimension of society and beyond.

"Anyone who thinks that anything is beyond the reach of capitalism today is being unrealistic."

The idea that Bezos, if he really wants to, might be able to buy the Mona Lisa and use the painting for whichever meaningless goal he pleases — including eating it — demonstrates that it is perfectly imaginable that in an ultimate battle between money and meaning, money wins. As such, this particular act of Jocondoclastie would constitute a significant technocapitalist tipping point. As the most significant painting in Western society, losing the Mona Lisa to a tech billionaire while collectively laughing about it would highlight the inherent fragility of meaning, and the consequent dominance of contemporary experiences of irony and nihilism. If everything that 'ordinary people' value can only exist by the grace of Big Tech's support or indifference, it is easy to understand why people would become emotionally detached from cultural objects, and develop ways to see the 'lulz' in anything.

Back to topWho cares about a conclusion?

There is no actual, material connection between Jeff Bezos, the Mona Lisa, and the concept of Jocondoclastie, and that is exactly the point. Bezos and the Mona Lisa are each other's counterparts. In a post-digital, globalised world of rapid social change, 'wicked problems' and raging capitalism, anything and everything is simultaneously imaginable and insignificant, precisely because the massive financial and technological power of some individuals can so easily crush and create things. In this sense, Bezos appears to be a well-chosen target for the change.org petition. As Bezos can be seen as a symbol for decreasing sociocultural values and increasing technocapitalist dominance, he might just as well destroy cultural objects in their material entirety while the nihilistic 'masses' witness the 'feast' for their personal thrill and horror. It would merely be the next phase of a process that Bezos and his counterparts had already started. After Snapchat's Mona Lisa lenses, Google's Mona Lisa 'art remix', and Amazon's endless stream of Mona Lisa posters, socks, puzzles, cups, Christmas ornaments and other knick-knacks (see Figure 4), making a spectacle out of the destruction of the actual painting, could be the meaningless icing on the cake.

References

Baehr, P. (2007). The “Masses” in Hannah Arendt’s Theory of Totalitarianism. The Good Society, 16(2).

Bizarre. (2009, May 6). Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/article/paris-bizarre

Byrne, D. R. (2008). Heritage as social action. In G. J. Fairclough, R. Harrison, J. H. Jameson, & J. Schofield (Eds.), The Heritage Reader (pp. 149-173).

Chen, J. (2024, May 1). Jeff Bezos’s homes: inside his more than $500 million property portfolio. Architectural Digest. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/jeff-bezos-homes-property-portfolio

Freedom Foundation. (2023, 8 november). Bezos left Washington because he can; we’re fighting for those who can’t - Freedom Foundation. https://www.freedomfoundation.com/washington/bezos-left-washington-because-he-can-were-fighting-for-those-who-cant/

Gertz, N. (2024). Nihilism and Technology.

Neuendorf, H. (2018, 28 maart). The Mona Lisa Will Not Be Going on Tour After All, the Louvre Says. Artnet News. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/mona-lisa-not-leaving-louvre

Tolstoï, G. (2024, May 17). La Jocondoclastie, ou l’envie de détruire la Joconde - Culturius. Culturius. https://magazine.culturius.com/la-jocondoclastie-ou-lenvie-de-detruire-la-joconde/

Zöllner, F. (1993). Leonardo’s Portrait of Mona Lisa del Giocondo. Gazette Des Beaux-Arts, 121, 115–138. http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2006/157