How Eva Vlaardingerbroek uses digital media to normalize radical discourse

Eva Vlaardingerbroek is a metapolitical influencer who actively shapes public discourse through her use of digital media. She engages in an ideological battle to reframe radical discourse as common sense. Her claim to represent the voice of the people has shaped her image as a defender of European identity.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Eva Vlaardingerbroek is a metapolitical influencer who actively shapes public discourse through her use of digital media. She engages in an ideological battle to reframe radical discourse as common sense. Her claim to represent the voice of the people has shaped her image as a defender of European identity.

Back to topIntroducing Eva Vlaardingerbroek

Eva Vlaardingerbroek is a Dutch legal philosopher and political commentator known for her radical beliefs and critiques of liberal democracy. She gained prominence through her strong opposition to 'globalism' and modern feminism. Over the years, she has crafted an image of herself as a defender of European cultural heritage. In her commentary, she advocates for the preservation of old European values and traditional family structures. These sentiments particularly resonate with right-wing audiences in Europe and the United States.

Vlaardingerbroek was born in 1996 in Amsterdam to a Protestant father and a Catholic mother. Both of her parents are active in the classical music industry. Instead of following in her parents’ footsteps by pursuing a career in the arts, Vlaardingerbroek decided to study law at Utrecht University. She subsequently completed her master’s degree at Leiden University. During her time as a student, Vlaardingerbroek became involved with the far-right political party Forum for Democracy (FVD).

In 2019, Vlaardingerbroek delivered a speech against modern feminism at FVD’s party congress (Forum voor Democratie, 2019). Vlaardingerbroek’s remarks received significant media attention, which stirred public debate. It was during this time that the Dutch media instilled Vlaardingerbroek with the title “shieldmaiden of the far-right”. In 2020, Vlaardingerbroek was included in FVD’s candidate list for the House of Representatives. However, at the end of that year, Vlaardingerbroek announced her departure from the party. After distancing herself from traditional politics, she became an online political commentator.

Back to topMetapolitical influencer

Metapolitics has undergone a significant transformation in the 21st century. While its roots lie in the anti-Enlightenment tradition and the intellectual efforts of La Nouvelle Droite, contemporary metapolitics reflect the influence of digital media. Maly (2023, p. 65) refers to this post-digital metapolitics as metapolitics 2.0. Metapolitics 2.0 is thus metapolitics fused with web2.0 ideology. Guillaume Faye played a crucial role in expanding metapolitics beyond intellectual circles. Unlike de Benoist, who focused on theoretical discourse, Faye stressed the importance of media presence and political engagement. He argued that metapolitics should not be confined to intellectual debate. Instead, metapolitics should actively shape political reality through various agents like politicians, activists, and digital influencers (Maly, 2023, 101).

The rise of digital media transformed metapolitics into a participatory phenomenon. The post-digital landscape enables metapolitical actors to bypass traditional gatekeepers and directly engage with a global audience (Maly, 2023, p. 85). Vlaardingerbroek represents this new breed of right-wing intellectuals who combine anti-Enlightenment ideas with the affordances of digital media. Through digital and street-level activism, Vlaardingerbroek engages in metapolitical work by shaping discourse on issues such as mass migration, cultural identity, and the alleged decline of Western society.

Vlaardingerbroek has managed to create a notable online presence. Her active engagement on social media platforms, such as Instagram and X (formerly Twitter), has gained her a substantial following. Vlaardingerbroek is especially successful on X, where she recently reached 1 million followers.

Building on the theoretical frameworks of metapolitics 2.0 and algorithmic populism, this article explores how Eva Vlaardingerbroek operates as a metapolitical influencer. More specifically, I will analyze how Vlaardingerbroek uses digital media to challenge liberal democratic values, spread radical discourse, and recontextualize traditionalist ideas for modern audiences.

Shieldmaiden of the far-right

After Vlaardingerbroek’s controversial speech about modern feminism in 2019, some Dutch journalists spoke out against her. To her own dismay, she was labeled as the "shieldmaiden of the far-right" and "aryan princess" (Vlaardingerbroek, 2020). In an article for De Volkskrant, Hassan Bahara referred to Vlaardingerbroek as "the stylized face of the radical right". Vlaardingerbroek publicly addressed the writer in a post on X, accusing him of character assassination (Vlaardingerbroek, 2019). It is evident that during this time, Vlaardingerbroek tried to reject the "radical" label she received from the Dutch press.

Fast forward five years later, and the opposite appears to be true. Vlaardingerbroek now proudly embraces her title as "shieldmaiden of the far-right". She also no longer shies away from the term "radical". In a recent interview (EWTN, 2024), Vlaardingerbroek expressed that she would rather be a radical in the fight against evil than a moderate. But what exactly is this "fight against evil" Vlaardingerbroek speaks of?

Scholars seem to have a hard time agreeing on a definition for the word "populism". The various interpretations have made populism an inflated concept (Maly, 2022, p. 34). Despite the lack of a robust singular meaning, there are some keywords that appear in all definitions of the word. This list consists of “the people”, “the voice of the people”, and “the elite” or “the establishment” (Maly, 2022, p. 33). Claiming to represent the voice of the people is a recurring strategy in Vlaardingerbroek’s political activism. This strategy relies on a moral binary that pits "the pure people" against "the corrupt elite". Vlaardingerbroek’s rhetoric embodies this dichotomy, as she consistently frames herself as a defender of Western civilization against progressive and globalist threats.

Back to topThe voice of the people

In July of 2024, Colm Flynn interviewed Eva Vlaardingerbroek on behalf of the global Catholic network EWTN. The interview was uploaded to EWTN’s YouTube channel with just over 1 million subscribers and has accumulated 184,000 views within 6 months. Vlaardingerbroek also shared the full interview with her followers on X (Vlaardingerbroek, 2024). In the interview, Vlaardingerbroek talks about her conversion to Catholicism, her opinions on mass migration, and the future of Europe. When asked what inspired her activism, Vlaardingerbroek expresses that she has always had an interest in taking a stand:

“I guess I had that from a young age. Even in high school I was someone who wanted to join the debate club even though that wasn’t so cool to do. I wanted to study law because I thought studying law was the right thing to do if you cared about justice in the world and you want to make a difference.” (EWTN, 2024, 3:05)

Vlaardingerbroek attributes her passion for politics and justice to her upbringing and education:

“I would say that my parents have instilled in me a desire and I guess moral obligation almost to look for answers, look for the truth, ask questions, be critical of the things that you hear and see around you.” (EWTN, 2024, 3:44)

Vlaardingerbroek presents herself as morally responsible to uncover 'the truth' and 'fight for justice'. In doing so, she, of course, also frames her discourse as a search for truth and justice. Flynn also refers to Vlaardingerbroek as one of the faces of the farmers’ protests in the Netherlands. In a nutshell, the protests were triggered in 2019 by a government proposal to cut down on livestock significantly. The proposal was made in relation to the climate crisis as an attempt to limit agricultural pollution. A lot of people, especially farmers, went out to protest these policies.

As the face of the Dutch farmers’ movement, Vlaardingerbroek has taken on the 'responsibility' of representing the voice of the people. She framed the farmer protests in a populist manner. She presented herself as the protector of the farmers (the people) against the government (the elite). Vlaardingerbroek used those protests in her online and offline activism and became a global star within the far-right in doing so. Her support for the farmers even got her airtime on Fox News (2022). The media (Niranjan, 2024) - or she herself - frames Vlaardingerbroek as someone who articulates the voice of the people, which further strengthens her populist claim (Maly, 2022, p. 43).

Back to topEngaging in an ideological battle

While it might seem like it at first glance, Vlaardingerbroek is not merely concerned with the well-being of Dutch farmers. Her interest in the movement serves a bigger purpose. Vlaardingerbroek claims that the new climate policies are part of a hidden government agenda. She accuses the Dutch government of taking land from farmers to house immigrants:

“We are a very tiny country. We have a lot of people. We also have a housing crisis and we have a growing population as a result of mass migration (…) so where are you going to put those people? More than half of the country is owned by farmers so the land is scarce and I think that our government could use a bit of extra land.” (EWTN, 2024, 7:15)

Vlaardingerbroek’s populist claim is used to inject far-right ideology into the public sphere. Her argument in the above quote aligns with the “Great Replacement” theory Guillame Faye and Renaud Camus popularized. This narrative claims that European populations are being replaced by non-European immigrants, leading to the decline of Western civilization. Faye connected the Great Replacement theory to the broader project of “reconquest” (Maly, 2023, p. 89). According to Faye, reconquest can be achieved through the renewal of archaic values and the re-establishment of homogenous groups. Framing migration in terms of colonization is a crucial step in the metapolitical mission. Vlaardingerbroek does this masterfully:

“I wouldn’t even call it immigration anymore. I think we are nearing what is replacement. You are replacing a population and I would like my nationstate to persist and to continue to exist and that won’t happen this way.” (EWTN, 2024, 9:10)

By framing immigration as a threat to national identity, Vlaardingerbroek reinforces the ethno-differentialist belief that homogeneity is essential for social stability. Ethno-differentialism promotes the idea that cultural and racial groups should remain separate to preserve their unique identities (Maly, 2023, p. 75). The reconceptualization of democracy as based on organic and homogenous groups is central to metapolitics. Metapolitical actors like Vlaardingerbroek appropriate progressive terms like “democracy” and recontextualize them to fit radical right-wing discourse (Maly, 2023, p. 71). Organic democracy is far from progressive. It is fundamentally anti-Enlightenment and is a direct attack against liberal democracy and universalism.

Flynn further asks Vlaardingerbroek if she believes that the Netherlands is becoming more divided like the United States. Vlaardingerbroek responds that polarization is not unique to the Netherlands but is happening everywhere in the western world. Vlaardingerbroek emphasizes that she does not consider this development a bad thing:

“I think that it’s only normal and right that with the radical positions that the people in power have taken over the past few decades that there is a counter-response to it. I think this is normal. I think it’s good. Often times I actually feel like the position that people in the opposition have taken, or myself on the ‘right-wing’, are quite normal positions or would have been deemed Christian democratic ideas and ideals 30 years ago and now it’s far-right.” (EWTN, 2024, 14:08)

Vlaardingerbroek asserts that polarization is not inherently negative but a natural counter-response to the “radical positions” taken by those in power. She portrays political division as a corrective force rather than a destabilizing one. Vlaardingerbroek’s rhetoric aligns with the idea that polarization simplifies political conflict into an “Us vs. Them” dynamic (McCoy et al., 2018, p.18), where one side is the victim of an unfair ideological shift. Vlaardingerbroek claims that her views, which are now deemed far-right, were historically aligned with Christian democracy. Vlaardingerbroek implies that the political mainstream has become radical while she is simply upholding traditional values. Ergo, she claims that she - and the people she claims to represent - are normal and mainstream, but because the elites radicalized, her position is now considered radical as well.

The selected quotes illustrate that Vlaardingerbroek engages in an ideological battle to normalize far-right discourse. This battle is not fought through traditional politics alone but also through cultural and digital activism. It is a metapolitical battle. Vlaardingerbroek’s ability to exploit digital media and recontextualize right-wing ideas enabled her to become a successful metapolitical influencer.

Back to topUptake

Understanding populism as a “mediatized chronotopic communicative and discursive relation” (Maly, 2022, p. 34) will help to explain why Vlaardingerbroek became so successful. Populism should be analyzed in its chronotopic context — its specific time-space situation. Contemporary populism is fundamentally shaped by digital media. Therefore, analyzing populism in the digital age requires attention to algorithms, affordances, and participatory media logic (Maly, 2022, p. 36). Populism is not merely a set of ideas; it is a discursive process. Rather than a fixed ideology, populism should be understood as a “communicative relation between human and nonhuman actors” (Maly, 2022, p. 36). It is not just about what populists say but also about how their messages are shaped by digital media and engaged with by audiences.

Blommaert (2019, p. 3) argues that modern political discourse is often irrational, aestheticized, and emotive rather than based on rational debate. This is evident in Vlaardingerbroek’s spiritual framing of the migration debate:

“I don't just see the fight that we're in as a political fight, I truly see it as a spiritual one. And I think that we all have a moral obligation to call out evil where we see it and if the result of that is that people think that that's radical then so be it. I would much rather be a radical in the fight against evil than be a moderate.” (EWTN, 2024, 16:22)

In post-digital political discourse, virality depends on discursive shape as well as discursive content (Blommaert, 2019, p. 3). Vlaardingerbroek does not seek broad agreement but embraces polarization. She is aware of the fact that sharp rhetoric travels further in algorithmic spaces. Political discourse today is interactive. Audiences do not just consume messages; they engage with and reproduce them in different ways (Blommaert, 2019, p. 7).

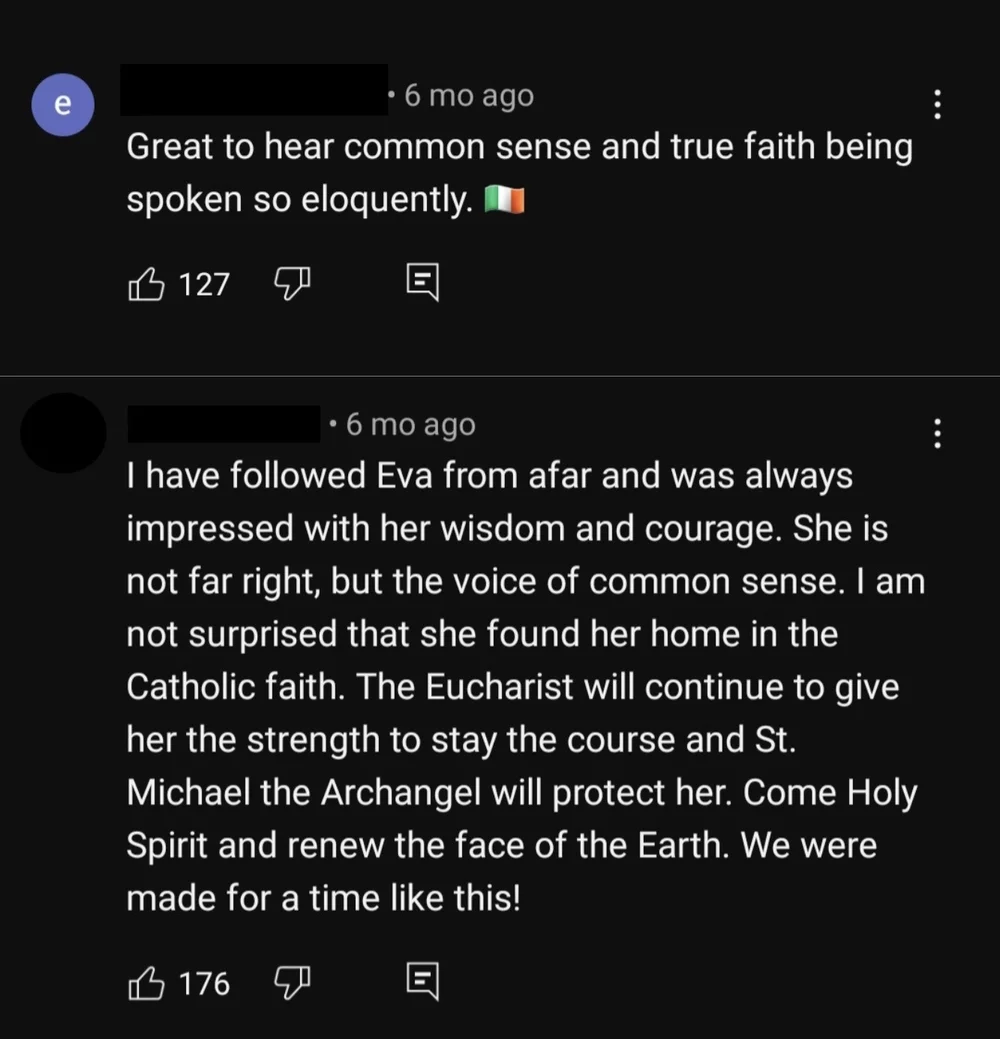

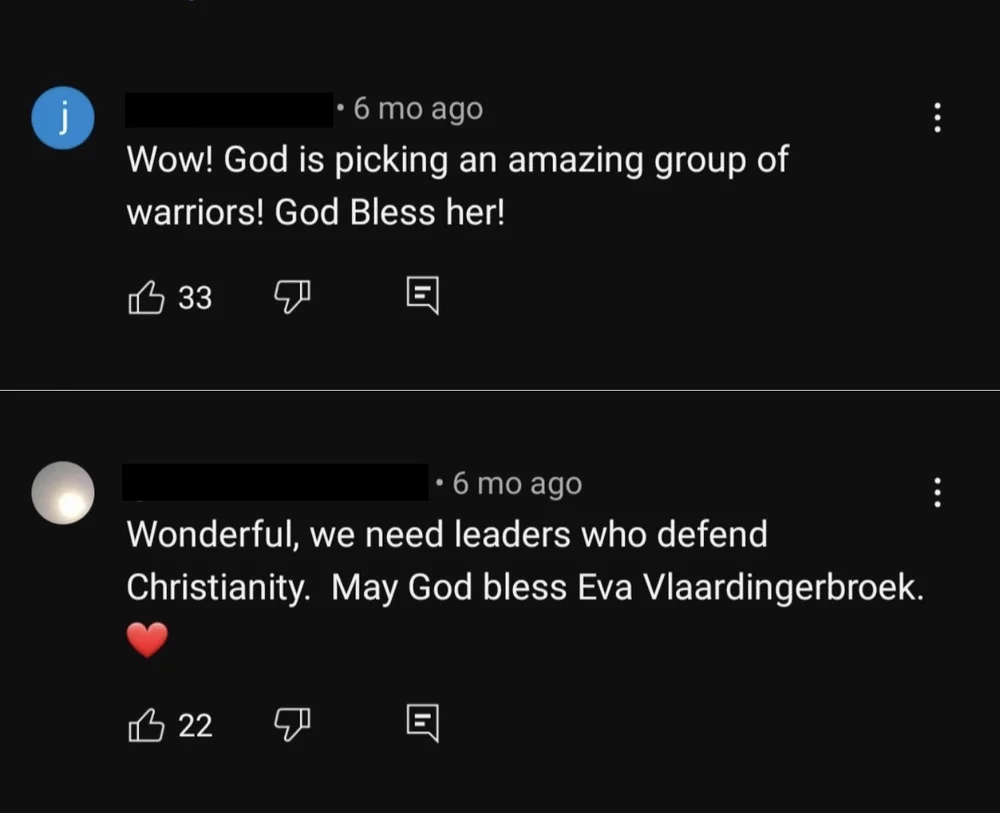

The YouTube comment section of Vlaardingerbroek’s interview with EWTN is distinctly positive. This indicates that her message reached the intended audience. The audience frames Vlaardingerbroek as "the voice of common sense”. The claim that Vlaardingerbroek is “not far-right” but speaks common sense aligns with the metapolitical strategy. It echoes Vlaardingerbroek's input discourse, and this reproduction gives legitimacy to her voice. The audience normalizes Vlaardingerbroek’s radical discourse by reframing her ideas as natural, necessary, and accepted. The audience characterizes Vlaardingerbroek as a defender of faith and reason.

Vlaardingerbroek is positioned as both a spiritual and political figure rather than just a far-right commentator. The warrior motif aligns with the new right’s rebranding of politics as a moral and cultural battle. This mirrors the identitarian movement, where figures like Vlaardingerbroek are seen as vanguards in a fight against globalism (Maly, 2023, p. 87). Vlaardingerbroek is framed as a defender of European Christian heritage against perceived threats like secularism and multiculturalism.

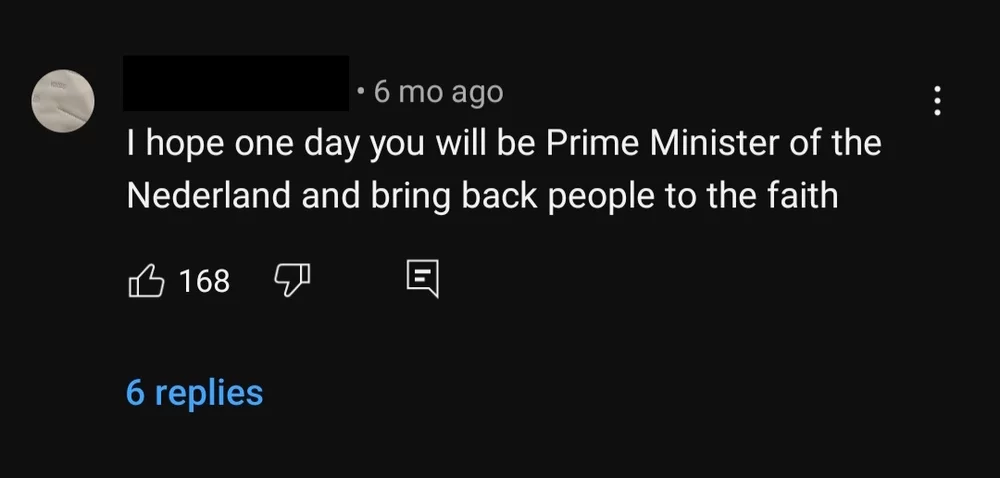

The comment “I hope one day you will be Prime Minister of the Netherlands” reflects how metapolitical influencers are increasingly viewed as viable political leaders. Vlaardingerbroek does not engage in traditional politics. Instead, she gains legitimacy through viral engagement. Vlaardingerbroek’s supporters actively shape her identity as a leader. Vlaardingerbroek may not have directly positioned herself as a future Prime Minister, but her audience constructs this image for her. This reflects the concept of populism as a “mediatized chronotopic communicative and discursive relation” (Maly, 2022, p. 34). Maly argues that populism is a frame of communication that let's the politician speak in name of the people. In a digital environment, this frame can only work if it is give legitimacy in the form of user interaction. Users needs to like, share and support the message in the comments and thus co-construct the legitimacy of this claim on the voice of the people.

Back to topFuture leader of the Netherlands

Vlaardingerbroek considers her political activism her “life’s mission” (EWTN, 2024). Through her work, she normalizes far-right ideologies in the name of giving power back to the people. Here, Vlaardingerbroek explicitly makes the populist claim to represent the voice of the people. When asked if she would like to get into Dutch politics again in the future, Vlaardingerbroek responds:

“I don’t think in the near future. I think I found my way outside of the political system and I operate way more freely.” (EWTN, 2024, 27:37)

Vlaardingerbroek’s decision to operate outside formal political institutions aligns with the metapolitical strategy of shaping public discourse and culture first before engaging in direct political action (Maly, 2023, p. 65). She is able to operate more freely because she bypasses traditional gatekeepers and engages directly with her followers. Flynn mentions the comments from fans who describe Vlaardingerbroek as the future leader of the Netherlands. He asks Vlaardingerbroek if she would like to lead the Netherlands someday. In true populist fashion, Vlaardingerbroek replies:

“If the people want me to.” (EWTN, 2024, 28:02)

Eva Vlaardingerbroek’s success as a metapolitical influencer demonstrates how digital media can be leveraged to normalize radical discourse. Vlaardingerbroek exploits the affordances of social media platforms to maximize engagement. She relies on polarization and conflict to enhance her visibility. Audience uptake is a crucial part of Vlaardingerbroek’s popularity. Her followers actively engage with her message, reinforcing her legitimacy as a political actor. Through this participatory process, Vlaardingerbroek’s message reaches a global audience.

Ultimately, Vlaardingerbroek’s case highlights how metapolitical actors gain influence in a post-digital age through media literacy. As a result of her media literacy, Vlaardingerbroek is able to bypass traditional gatekeepers and reshape public discourse. Vlaardingerbroek successfully navigates algorithms and engages audiences in her attempt to wage an ideological battle. Vlaardingerbroek’s ability to normalize radical ideas reflects the importance of digital media in transforming politics.

Back to topReferences

Blommaert, J. (2019). Political discourse in post-digital societies. (Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies; No. 236)

EWTN. (2024, July 11). Eva Vlaardingerbroek on becoming Catholic [Video]. YouTube.

Forum voor Democratie. (2019, December 2). Eva Vlaardingerbroek over hedendaags feminisme. Retrieved December 15, 2024, from

Maly, I. (2022). Populism as a Mediatized Communicative Relation: The Birth of Algorithmic Populism. In C.W. Chun (Ed.). Applied Linguistics and Politics (pp. 33–58). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Maly, I. (2023). The birth of metapolitics 2.0. In Metapolitics, Algorithms and Violence: New Right Activism and Terrorism in the Attention Economy (1st ed., pp. 65–106). Routledge.

Niranjan, A. (2024, January 16). Why Europe’s farmers are protesting – and the far right is taking note. The Guardian.

Vlaardingerbroek, E. [@EvaVlaar] (2019, December 7). (1/12) Dankzij activist, Hassan Bahara, sta ik vandaag op het zaterdagkatern van de @volkskrant als “het gestileerde gezicht van radicaal rechts” [Image attached] [Post]. X.

Vlaardingerbroek, E. [@EvaVlaar] (2020, June 18). Na “arisch prinsesje” te zijn genoemd door @HDDuurvoort, “dienstmaagd van radicaal rechts door @Oostveenm, word ik nu door @danielahoogh “braaf [Post]. X.

Vlaardingerbroek, E. [@EvaVlaar] (2024, July 30). Absolutely loved doing this interview with @colmflynnire for @EWTN. We talked about why I became a Catholic, my views on [Post]. X.

Back to top