How convergence culture makes BoJack Horseman possible

The way we watch television has drastically changed since the nineties. We no longer simply consume, we participate. This article examines BoJack Horseman as a case study to explain how convergence culture has altered the way we consume media.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Since the nineties, a lot has changed in regards to how we enjoy our favourite media. Shows like BoJack Horseman manage to engage with their fans, even outside of the original content. How does participatory culture work and what is a complex narrative?

Back to topFrom the couch to online

Those of us who grew up before Netflix was even a thing will remember the agony of trying to watch a TV show in its entirety. You would either need to be incredibly patient and wait for a new episode of your favourite show every week. Assuming it was airing chronologically. Or, if you were lucky, you could buy a DVD boxset. Either way, this made binging shows fairly difficult, because no one really feels like getting up from the sofa to change the disk every few episodes. And binge-watching is exactly what shows like BoJack Horseman thrive on.

In the nineties everything slowly started to change. Online communities started to emerge. We could suddenly interact with other fans. We could create fanzines, share our thoughts in online chatrooms and create fanart or fanfiction. This resulted in what we now call participatory culture. (Jenkins, 2006) Fans are no longer passive viewers who simply consume. Fans are now also creators. In some cases, they’ve even started having active roles in how a storyline might pan out.

Participatory culture is a side-effect of convergence culture. According to Henry Jenkins the line between television producers and viewers ha been blurred. (Jenkins, 2006). Fans are actively encouraged to seek out new information about shows and other media. This is in stark contrast with the way we used to engage with our favourite TV shows.

Back to topBoJack Horseman

Convergence culture makes way for narratively complex storylines on television. This new model of storytelling is an alternative to the conventional episodic programmes that we were used to from American television. (Mittell, 2006) Stories no longer need to be wrapped up within one episode, but can instead extend over several seasons. This allows for more creativity and in-depth character development. For instance, creators can play with genres as will become clear later on in this article.

One such television show is Netflix’s BoJack Horseman. BoJack Horseman tells the story of a failed actor who was once the star of the popular sitcom “Horsin’ Around”, where he was the father of three orphans. An important thing to note is that BoJack is in fact a horse, much as his name would suggest. A lot of the characters are anthropomorphic animals, with a few exceptions.

BoJack is a self-centered yet insecure character who is addicted to various drugs and alcohol. He tries to find happiness and approval through his countless efforts to relaunch his career or to, in the very least, live off of the residuals of his past fame.

Other important characters are Princess Caroline, a pink cat who is BoJack’s past lover and also manager. Todd, a young slacker who gets into all sorts of trouble and who somehow managed to become a permanent resident on BoJack’s couch. Diane, a young Asian woman who in the first season tries to help BoJack with his memoire. And Mr. Peanutbutter, a happy-go-lucky Labrador who, unlike BoJack, is well-liked and still manages to find success within the acting business. He is basically the antithesis to BoJack.

Through interacting with these characters every season, BoJack slowly finds some character development. The show plays with this fact by subtly changing the intro depending on what’s going on in the story. Essentially, if you’ve ever missed an episode, all you’d have to do is watch the intro and you’re up to speed with how everyone is doing. In relation to BoJack, of course.

Back to topGenre switch

As mentioned before, convergence culture has allowed for more narratively complex storytelling. This is partially due to the advancements of technology. According to Henry Jenkins, the word "convergence" refers to the technological, industrial, cultural and social changes. After all, convergence culture is where old media and new media collide (Jenkins, 2006). As one medium is slowly replaced, so can stories be told in more innovative ways. This new way of storytelling can be referred to as a "narrational mode". According to David Bordwell, this means creators aren't bound to certain genres or specific creators, but rather have the freedom to experiment (Mittell, 2006). This allows people to borrow from each others' expertise.

Fans are no longer passive viewers who simply consume

Although the show is meant to be a satirical comedy it has also dabbled in other genres. In one episode, titled “Fish Out of Water”, almost the entire episode is silent. The creators cleverly play with concept of silent films by putting their own spin on it. BoJack finds himself at an underwater film festival to promote Secretariat . He wears a special oxygen-filled helmet the entire episode. This makes it impossible to talk, apart from when you use a special device built into the helmet (although BoJack doesn’t realise that until the very end of the episode). Interestingly, the story continues as normal. You see BoJack trying to make amends with someone whom he hurt in a previous episode, while struggling with this new “handicap”.

Another example is the episode “Showstopper”. At this point in the story, BoJack is struggling to cope with his depression and starts using heavy pain medication, which causes him to lose touch with reality. The story is now told through a detective show and a regular episode. The whole episode you see BoJack confusing the TV show he’s working on with real life. He becomes paranoid and treats his real life as if he were really a detective.

BoJack Horseman also cleverly intertwines real life and satire. For instance, in the second season we’re introduced to a charismatic hippo named Hank Hippopopalous. In the public eye he is a well-loved host of various TV shows but behind the scenes he appears less than friendly. Hank is a representation of what happens in Hollywood when a famous person is accused of sexual harassment. His storyline is reminiscent of what was happening with the Bill Cosby rape allegations at the time and also the allegations made against David Letterman by his former assistants.

Back to topParticipating with BoJack

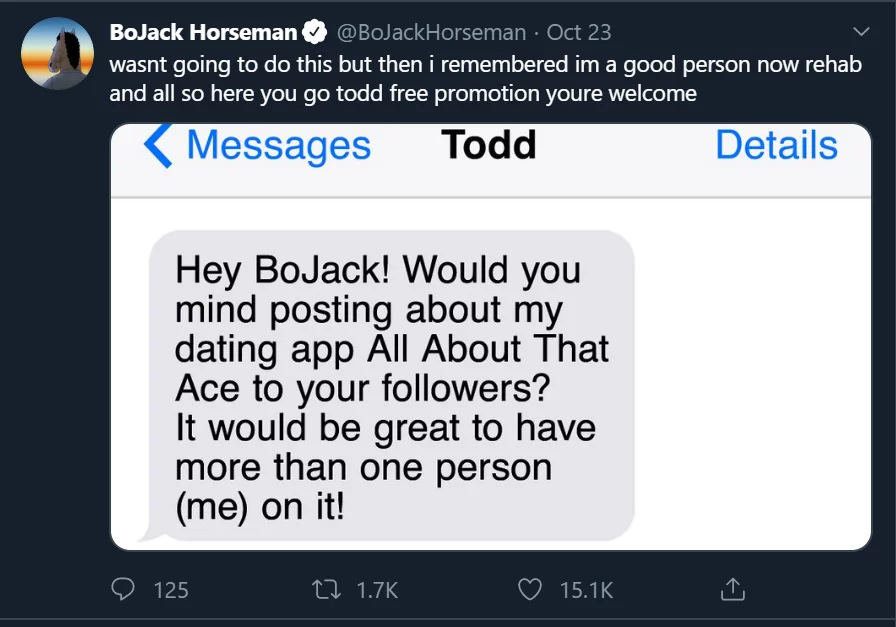

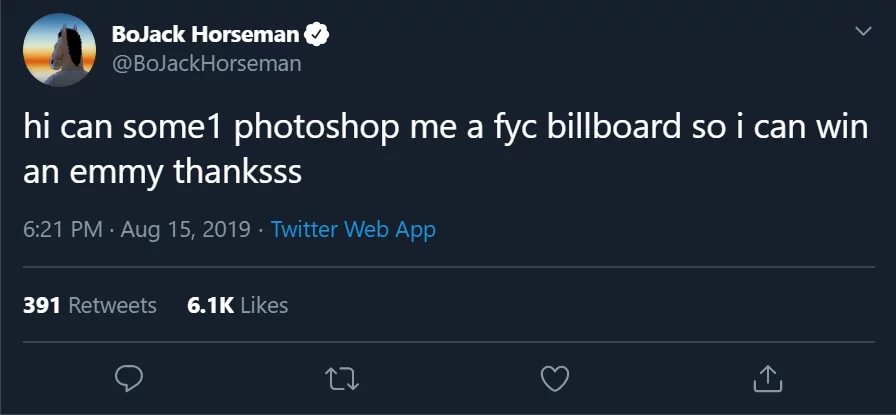

The storyline isn’t just contained within the framework of the television show. Instead it lives on through a Twitter account run by BoJack himself. It’s almost as if viewers can have real life interactions with their favourite alcoholic horse. “Real life” BoJack makes references to previous episodes, entices fans with silly tweets and shares fan edits.

Being a viewer of BoJack Horseman is anything but a passive pastime. The “real life” BoJack encourages his fans constantly to engage with the show. This ties in perfectly with what we discussed before in regards to participatory culture. For instance, in August of this year he asked his followers to photoshop billboards for him so he could get an Emmy. This is a direct reference to the fact in the show he, try as he might, cannot seem to acquire such a prize. Something always happens, causing him to lose out on his one dream, winning an Emmy.

Fans happily obliged and sent in various billboard designs to the twitter account, so as this example. It was inspired by an episode, where Princess Caroline, BoJack and his marketing team are trying to figure out what the billboard should be for BoJack’s upcoming show Philbert. This shows fans are taking the content of the show and using it in a proactive way to show their devotion.

A new age

Convergence culture has allowed us to enjoy our favourite shows when we want and how we want. The days of waiting in front of the TV for our show to start are over. It brings us closer to the stories we love and allows for more complicated narratives. And if our show is over, we needn’t worry because online we can participate in our own content creation through fanart or fanfiction. If that’s not enough, we can simply discuss the latest news with other fans. Or with our good old friend BoJack Horseman.

Back to topReferences:

Jenkins, H. (2006). Introduction: “Worshop at the Altar of Convergence.” in Convergence culture: where old and new media collide. New York: New York University Press.

Mittell, J. (2006). Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television. The Velvet Light Trap 58, 29-40.

Netflix. (2014). BoJack Horseman.

Back to top