Google Maps' commercially oriented representation of the world

Google Maps displays a commercially oriented representation of the world. This influences how map users perform in the represented space. However, this subjective representation is obscured by the app's widespread use and its features' framing.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Maps are generally known as neutral tools that can be used to transfer objective information. However, though maps are often used to present objective information, they are not just neutral conveyers of that information. In fact, maps always represent the specific point of view of the map maker which is inevitably influenced by commercial, ideological or political factors. This article explains the consequences of Google Maps' commercially oriented representation of the world.

Back to topCritical cartography

For a long time, the aim of the academic practice of cartography has been to display the earth in the most objective way possible. Consequently, maps gained the general appearance of a neutral tool that can be used to visualize scientifically obtained information. However, when from the 1980s onwards scholars in the field of critical cartography started to critically analyze cartography practices, they argued that these “objective” terms are contingent on the social, historical and political contexts in which maps are produced and used.

Since then, the neutral and scientific image of maps has been a topic of debate. Instead of regarding maps as ontologically secure tools ( world can be objectively mapped by using scientific tools to capture and display spatial information), critical cartographers started to investigate the social, cultural and technical contexts that determine how and why are maps are produced and used. (Crampton 2003, Kitchin and Dodge 2009)

Back to topThe Mercator projection

Consider the famous Mercator projection. This map is designed in 1569 by the Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator for nautical navigation and it is still one of the most displayed and used maps in the western world (it is for example the base map of Google Maps). Like any world map, it shows distortions in the projection of land areas for it is difficult to represent the spherical reality of the world in relative proportions in a 2D format. In this map, the sizes of areas far from the equator are exaggerated in comparison to areas close to it. For instance, Greenland appears the same size as Africa, while in reality the continent of Africa is fourteen times bigger. Many scholars – and others – have criticized this projection for it does not simply “facilitate nautical navigation, but instead serves to reiterate colonial domination by demonstrating the centrality and global importance of Europe.” (Harpold qtd. by Farman 2010: 871)

Google’s representation of the world is focused on commercial interactions

The Mercator projection was initially designed for navigational purposes for which it still serves as a useful tool. However, it is not appropriate as a representational projection of the world due to the depicted area distortions. Yet, when atlas- and mapping platform designers apply this projection as their base map, for many people (at least the billions of Google Maps users and everyone who used this map in a school atlas) this flawed projection serves as the “real” representation of the world. Thus, not the distorted areas are the source of the problem – since those do not interfere with the intention of the map; navigation – but rather the problem is the context in which this map is displayed and used. he map’s contextual framing that makes it seem a neutral conveyor of objective information.

Back to topMaps influence how you act

This has consequences. Think, for instance, about the time when you blindly followed the directions of your GPS device to end up on a road which turned out to be inaccessible for cars: maps influence how users perform in the represented space. Another example , for example, when maps raise or lower expectations about a landscape to be visited; “walking through an area demarcated as ‘wilderness’ on a map might elicit a more (or, indeed, a less) satisfying ‘nature’ experience as a result of expectations set by the map.” (Harris and Hazen 2009: 61)

In turn, this might influence patterns of mobility: “A tourist looking at [a ‘protected area’] map may consider seeking out such spaces to have a ‘wilderness experience,’ or indeed may avoid such areas assuming that there will be nothing of interest for them.”(61) Maps influence a user’s movements which in turn reaffirm the represented understanding of this space the map displays. (Del Casino and Hanna 2000, 2006) That is what happens when you follow the directions of your GPS device to end up stuck in a narrow road, like this truck driver: the map’s contextual framing – a usually reliable navigation device – made seem ontologically secure.

Google Maps

Now, let us look from this perspective at the most used map of the world: Google Maps. With more than five billion app downloads, Google Maps is the most used map for daily life navigational purposes worldwide. Also, Google Maps hosts a participatory community of over 120 million users who actively contribute pictures, reviews and other information. And, Google Maps is the most widely used mapping service for third parties; thousands of companies, such as Uber, Booking.com and Takeaway.com, make use of Google’s map to provide their location-based services.

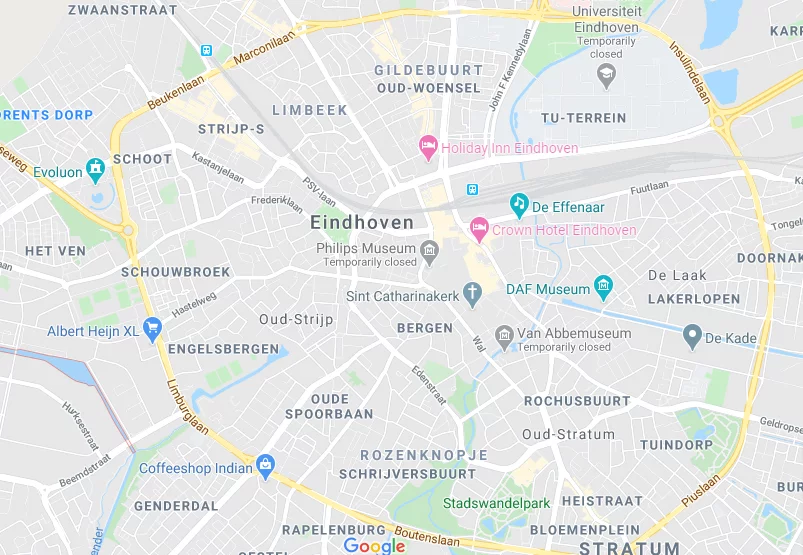

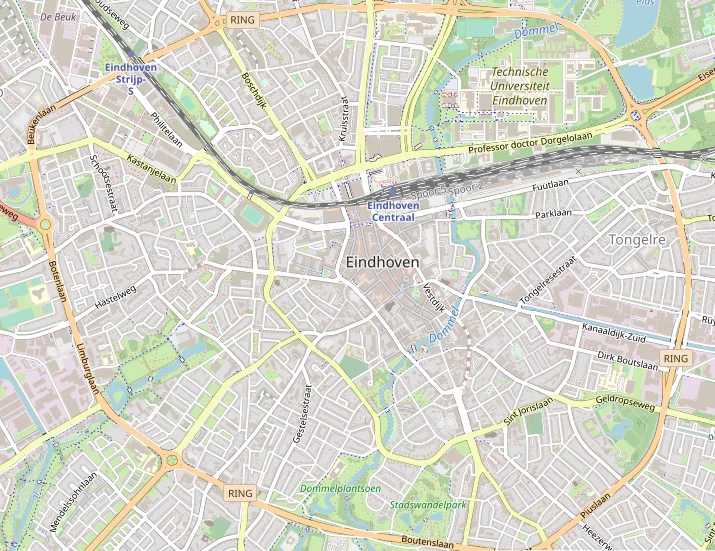

Like any map, Google Maps shows a partial perspective on the world. Invariably, the map-making motive coincides with the information that is displayed on the map: Google’s representation is focused on commercial interactions. Consider these two representations of the city of Eindhoven by Google Maps and OpenStreetMap. The distinction between the two becomes visible by noting the most eye-catching aspects on Google Maps: the symbols and names indicating companies. Furthermore, Google Maps depicts algorithmically generated highlighted areas which represent a high concentration of commercial activity. This representation corresponds with Google’s business model which is based on gathering and selling user data and providing advertisement opportunities for other companies. The map is designed to fit this business strategy.

Google Maps and the Local Guides community

Further, this commercial orientation is prevalent in Google Maps’ participatory community. Users are invited to contribute their local knowledge to Google Maps by joining the Local Guides community. Local knowledge, that is, mainly information about companies and touristic areas such as reviews, pictures and videos all in the context of updating “points of interest” i.e. business or touristic information. Users receive benefits like special Local Guides-badges which indicate their “level” on their personal page, extra (temporary) Google Drive storage, early access to new Google products and, if lucky, a special pair of socks for Christmas.

The Local Guides meet on the Local Guides Connect forum, a social networking platform moderated by Google employees. On the platform they share their thoughts, pictures, ideals suggestions organize meet-ups and become friends. Further, Google hosts the annual Connect Live event. For this event, around 150 Local Guides are selected from thousands of applications to join an all-inclusive week in a hotel in the United States. The gamified rewarding system is quantity based: the more someone contributes the more one receives. As of 2020, more than 120 million Local Guides participate in the program.

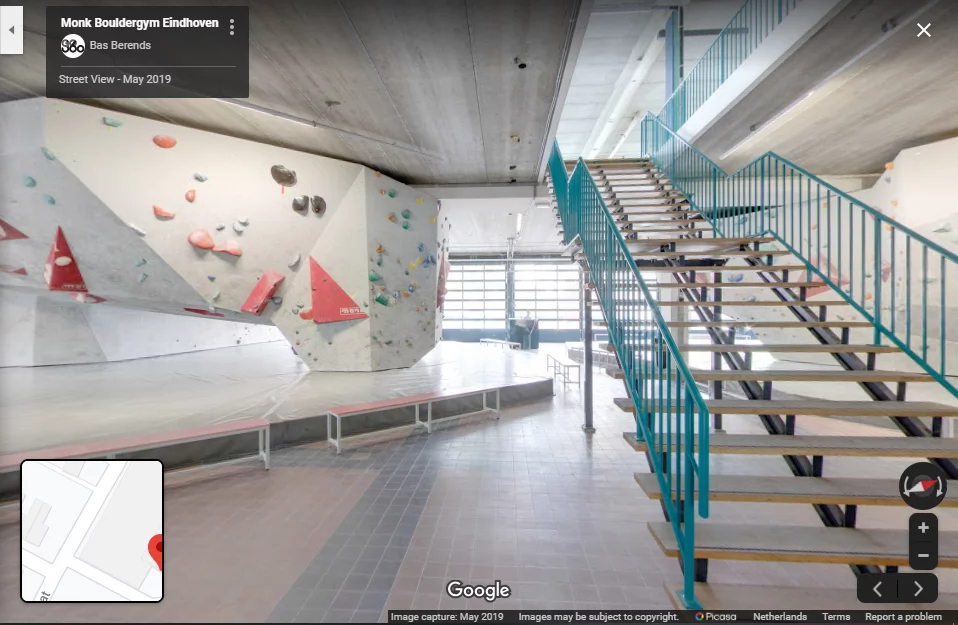

Back to topTrusted Photographers

Additionally, users can contribute to the map as a Trusted Photographer. These contributors ought to invest 3,500 dollars in a specific GPS connected camera and use it to shoot 360° imagery for Street View or the interior of companies (the latter goes under the of Virtual Tours). As a reward for these contributions, the photographers are granted the rights to profile themselves as a Google Trusted Photographer. Consequently, Trusted Photographers offer their services to companies that aim to improve their visibility on Google Maps. In Eindhoven, for example, a company asks for a fee ranging from 250 to more than 525 euros for an interior shoot of 360° pictures.

Database maintenance

Although some Trusted Photographers have found a way to exploit this process of user participation, it is not difficult to recognize the value that is in it for Google Maps itself. The input coming from user participation is recentralized around Google’s corporate interests: it is used both to enhance the accuracy of the map and to gather profitable user data. This has led Plantin (2018) to argue that in Google Maps, user participation is channeled to work as a form of database maintenance.

A few examples. Because the uploaded Street View imagery is geo-located, it can be used to track the roads which the providers followed to check whether these roads correlate with the roads displayed in the map. Secondly, the images are analyzed by optical character recognition (OCR) software to recognize words and symbols such as road names and house numbers. This extracted information is used, for example, to read road signs and improve route suggestions. (Madrigal 2012)

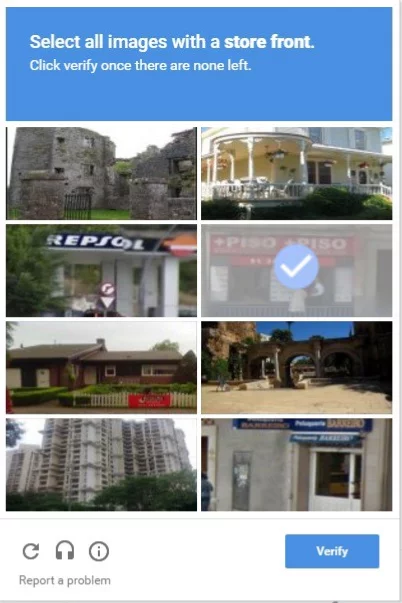

Further, to verify the outcomes of the OCR analysis, the verification software of reCAPTCHA is used. (McQuire 2019: 155) When stumbling upon this verification, users must select the images which depict a certain subject, such as a store front, from a collection of street view imagery. These selections are used to improve the process of OCR analysis of Street View data.

Counter-mapping discourse

By using these kinds of methods, user participation is channeled not so much to create content, but rather to maintain the database. (Plantin 2018: 499) This conflicts with the kind of promotional language that is used to attract participants for these programs: Google frames its map in the Local Guides community as an empowering counter-mapping tool. Counter-mapping, which is related to the academic field of critical cartography, refers to the effort of mapping against dominant power structures with the aim of effectuating social or political change. See for example the Mapping Prejudice project which maps real estate contracts that contain covenants that reserved land for the exclusive use of white people to show how racial restrictions are embedded in the physical landscape.

Online invisibility is a problem created by Google Maps and other reviewing platforms like TripAdvisor and Yelp in the first place.

Google attracts Local Guides by generating and maintaining the idea that they are helping others. During the Connect Live event in 2019 a Google spokesperson mentioned that all the reviews and pictures uploaded by Local Guides had generated a total of 3.5 billion views. In other words, the Local Guides had helped others 3.5 billion times. ecause “helping” involves providing others with reviews and pictures so they can make “the best decisions about the things worth doing.”

Further, Local Guides are helping local businesses by improving the visibility of those businesses on Google Maps. In a Local Guides recruiting video posted by Google Maps on YouTube, a Local Guide shows her dedication to adding reviews of local businesses run by women to make them better well-known with the following motivation:

"My ultimate goal is to inspire women to follow their dreams. … I hope that by adding businesses on Google maps it will change the mindset to “Yes, women can run businesses successfully, women are strong, inspiring.” Do whatever small thing you can do and together we can move mountains."

This video shows a clear example of how Local Guides are told to be helping others: both the businesses they reviewed and the other map users who are now enabled to base their decisions on the provided information.

Back to topThe problem of online invisibility

In the Local Guides community, Google Maps is framed as an empowering tool which can be used in creative and counter-hegemonic ways, for example to pursue feminist aims. However, the user-generated data is primarily used to maintain Google’s database, and not so much to support charitable goals. Although online visibility might increase the revenue for small businesses, and the efforts of Local Guides possibly really help those shop owners, the fact that online invisibility is created by Google Maps and other reviewing platforms like TripAdvisor and Yelp in the first place.

By discursively constructing local businesses as invisible, and Local Guides as empowered, Google’s economic-oriented mapping effort is framed as a means for socioeconomic inclusion

The visibility of places on those platforms is determined by the amount of information, pictures, positive ratings and reviews that have been uploaded by users. And the information presented at these platforms influence a user’s choice. Therefore, Firth (2017) has argued, online invisibility can have very real effects on where people go. Uneven access to those websites due to limited internet access and digital illiteracy might cause an unequal representation of places. This renders the underrepresented parts of the city invisible online. Consequently, “the rich get richer, the poor get poorer.” (547) For (small) companies, online invisibility is a real problem, though this problem is created by the review-based platforms, such as Google Maps.

Back to topTech solutionism

By presenting the Local Guides program to overcome this problem of online invisibility, Google demonstrates a strategy of tech solutionism. This strategy is also exposed by Luque-Ayala and Neves Maia (2019) in their research concerning a Google Maps mapping project in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. The aim of the project Tá No Mapa (‘It’s on the Map’) was to enhance the socioeconomic inclusion of informal settlements by putting them on the digital map. By discursively constructing the favela as “invisible” and “disconnected” from the rest of the city, Google Maps presented their mapping project as a way of providing visibility whilst helping to overcome systematic exclusions.

Local favela inhabitants were asked to map “points of interests”, though under the condition that these points are of interest for possible tourists. The authors argue that instead of addressing the needs of the local inhabitants, Google prioritized economic over social forms of inclusion, and this project turned out to be a neocolonialist mapping effort focused on economic incorporation.

The Local Guides program works in a similar way. By discursively constructing local (women-owned) businesses as invisible, and Local Guides as empowered, Google’s economic-oriented mapping effort is framed as a means for socioeconomic inclusion. However, the problem of online invisibility is created by Google Maps itself, and local businesses must abide by the rules of this platform in order to not miss out on income.

Back to topConsequences

The consequence of this commercially-oriented representation of the world is that the people living in the physical world the map represents increasingly change their habits to comply with the logics of the map. The contributors believe they are making a difference by helping others, while actually they only help to improve Google’s database. And by doing so, they consolidate Google Maps’ commercially oriented representation of the world in which online invisibility is indeed a problem.

Maps display a specific point of view. And that by using a map, you are supporting the particular point of view of its maker.

On Google Maps, the representation of the world is influenced by commercial motives: it is in Google’s business interest to make companies’ online visibility dependent on a gamified system like the Local Guides program. But the framing, scale of use and application in third party services obscure Google Maps’ commercially oriented subjectivity and give the map the appearance of a neutral, ontological secure tool that can be used for counter-mapping purposes.

Back to topConclusion

The consequences of Google’s obscured commercial subjectivity can be counteracted by raising awareness for the partial perspective of maps in general. (Propen 2009: 115) Counter-mapping initiatives can work to emphasize the partial perspectives of popular maps by representing the world from a different point of view. Alternative, non-commercial or activist mapping platforms can work to destabilize the ontological security of maps and emphasize that any map’s creation is motivated by ideological, political or commercial interests. Further, other mapping platforms such as the collaborative mapping project OpenStreetMap (on which the visibility of places is independent of commercially motivated conditions like the amount of positive reviews) can work as favorable alternatives to Google Maps.

Finally, every map displays a partial perspective. A complete, neutral and still useful map can never exist: Jorge Luis Borges described in “On the exactitude of Scienc", his famous short story of 1946 the empire where the science of cartography becomes so exact that the cartographers produced a map on the same scale as the empire itself – the map was completely useless. Fortunately, there are plenty of useful maps around. However, before making a decision based on a map; from using the Google Maps API on your website; using location data provided by Google to manage an epidemic; to choosing a map for daily navigational purposes; it should be common knowledge that maps display a specific point of view. And that by using a map, you are supporting the particular point of view of its maker.

Back to topReferences

Borges, Jorge Luis. (1946) “On the exactitude of Science.” A Universal History of Infamy. Original title: “Del rigor en la scienca” Translated by Norman Thomas. Penguin Books, London.

Crampton, J. (2003) The political mapping of cyberspace. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Del Casino, V.J. and Hanna, S.P. (2000) ‘Representations and identities in tourism map spaces.’ Progress in Human Geography, Vol. 24(1) pp. 23–46.

Del Casino, V.J. and Hanna, S.P. (2005) ‘Beyond the “binaries”: A methodological intervention for interrogating maps as representational practices.’ ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, Vol. 4(1) pp. 34–56.

Farman, J. (2010) “Mapping the digital empire: Google Earth and the process of postmodern cartography.” New media & society. Vol. 12(6) pp. 869-888.

Frith, J. (2017) “Invisibility through the interface: the social consequences of spatial research.” Media, Culture & Society. Vol. 39(4) pp. 536-551.

Harris, L. and Hazen, H. (2009) “Rethinking Maps from a More-Than-Human Perspective: Nature– Society, Mapping And Conservation Territories.” Rethinking Maps: New Frontiers in Cartographic Theory. Edited by Rob Kitchin, Chris Perkins and Martin Dodge. pp. 50-67.

Kitchin, R. and Dodge, M. (2007) “Rethinking Maps.” Progress in Human Geography, Vol. 31(3) pp. 331-344.

Luque-Ayala, A. and Neves Maia, F. (2019) “Digital territories: Google maps as a political technique in the re-making of urban informality.” Environment and Planning: Society and Space, Vol. 37(3) pp. 449–467.

Madrigal, A. C. (2012) “How Google Builds Its Maps—and What It Means for the Future of Everything.” The Atlantic. Accessed 25-05-2020.

McQuire, S. (2019) “One map to rule them all? Google Maps as a digital technical object.” Communication and the Public, Vol. 4(2) pp. 150-165.

Plantin, J. C. (2018) “Google Maps as Cartographic Infrastructure: From Participatory Mapmaking to Database Maintenance.” International Journal of Communication, Vol. 12 pp. 489–506.

Propen, A. D. (2009) “Cartographic Representation and the Construction of Lived Worlds: Understanding Cartographic Practice as Embodied Knowledge.” Rethinking Maps: New Frontiers in Cartographic Theory. Eds: Rob Kitchin, Chris Perkins and Martin Dodge. pp. 113- 148.

Back to top