Globalization, Translation and Feminism in Korea

Korea has long been a patriarchal society, whose language itself contains a gender hierarchy. However, since western feminism was introduced to the country, a both Korean women and Korean society changed profoundly.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

On this page

- Translation and feminism in Korea

- Translation and Women

- Translation in Korea: Translation of Foreign Texts and Escape from the Traditional Feminine Virtue

- The mpact of Hybridization: The ew Female Identity in Korean Translation

- Korea in the 'translated worlds': Keeping the gender hierarchy 'invisible' in Korean translation

- References

The case of Korea clearly shows how globalization, translation, and the western feminism ideology gradually established a new female identity and a new way perspective of the society towards women. In this articlet, I show that even in a very closed and conservative country, foreign interactions and the inflow of new ideologies can trigger a tremendous change not just on the people, but the society as a whole.

Back to top

Translation and feminism in Korea

Globalization is not a new phenomenon, but has evolved throughout history for hundreds of years. The sharing of different knowledge and culture that transcends borders is not a new story. It has been practiced long before the days of what we call the ‘recent’ years. One remarkable medium that enabled the interaction between nations was translation that surpassed the limitation of interaction due to the differences between languages.

In Cross-Cultural Management: A Knowledge Management Perspective (Holden, 2002), translation is described as “by far the oldest universal practice of conscientiously converting knowledge from one domain (i.e. a language group) to another”. One step further, translation is also “a kind of knowledge conversion, which seeks to create common cognitive ground among people, among whom differences in language are a barrier to comprehension" (Holden, 2002).

This change of thinking among Koreans as an effect of western ideology cannot be dubbed as Westernization.

This article will focus on the power of translation in ‘knowledge conversion’ and in creating ‘common cognitive ground’. Translation opened the gate for the inflow of western feminism into the strictly patriarchal Korean society, which changed the perception of womanhood and led people to question the gender equality in Korean translation.

This change of thinking among Koreans as an effect of western ideology cannot be dubbed as Westernization. Rather, the notion that ‘women should be treated equal as men in Korean translation’ can be considered as the result of hybridization of western feminism and Korean language accomplished by western feminists and enlightened Korean women together.

In order to elaborate this complex hybridization process, it seems crucial to examine the long-term interaction between translation and women of the past, the transitional stage when translations of foreign works spread in Korea and triggered the shift in Korean women’s identity, and finally the establishment of the new hybrid perspective of Koreans of today that critically views translation in regards to gender equality.

Back to topTranslation and Women

The relationship between translation and women is ambivalent. Translation was a tool for both confinement and liberation of women. History shows that while translation kept women in the subordinate position by using languages that reinforce sexual inequality, at the same time, it also enlightened women of their new roles as an equal 'individual'.

In the 17th century, the stereotypical image of women was directly applied to describe translation: translations are "les belles infidéles", which means that “like women, translations must be beautiful or faithful" (Simon, 1996). Traditionally, women were used as ‘metaphors’ for translation, specifically with their fidelity, passivity and purity, which intensified their inferior status compared to men. However, translation also allowed women to reveal and appeal their inequality and oppression to the world.

The Canadian Feminist translation project in Quebec that took place in the 1990s, was a collaborative work of feminist translators to seek for new ways of expressions in translation to free language and society from patriarchal burden. Their translation practice was “a political activity aimed at making language speak for women” (Simon, 1996). This unprecedented approach to translation gradually started to shift the invisibility of women to visibility not only in translation, but also in real life. Consequently, now in the contemporary globalization era, many feel a sense of uncomfortableness or wrongness when they see a translation that incorporates any lines of sexism.

The perspective of viewing translation in such way originally stemmed from the western countries, but spread throughout many parts of the world and has become ‘global’. Such influence of translation in enhancing women’s status also reached nations where the strong patriarchal culture inevitably collided with it, for example, in South Korea. The nation has long been a highly patriarchal and conservative society.

However, translation opened the door to many opportunities for women throughout the Korean history. Translation awakened women, and they awakened the society. Over the course of time, the deep interaction between translation and women formed a ‘global, hybrid, transnational, collective identity’ around the world that observe how women are treated in translation. This was also applied to Korean translation by applying the western feminism ideology into the Korean language, which had a strong gender hierarchy embedded in it. This can be viewed in the framework of ‘hybridization’, the combining of two distinctly different culturs and languages. That is, the female identity in the western countries became transnational, expanded its influence to the Korean society via translation, and thereby gave Koreans the new spectacle of perceiving the gender hierarchy in Korean translation as a ‘problem’.

Translation in Korea: Translation of Foreign Texts and Escape from the Traditional Feminine Virtue

Korean society has long been patriarchal under the strict Confucian culture. During the Joseon dynasty era, the invention of ‘hunmin jeongeum' (Korean language)’, allowed the translation of many Chinese works. During this time, many Chinese educational texts were used to teach educate women about the feminine virtues: being a wise mother and a dutiful wife. The translation of Chinese texts for women “was considered crucial in maintaining social stability”(Hyun, 2004).

In other words, translation only strengthened the fixed gender hierarchy in the Korean society and confined women in the ‘traditional roles’ decided by men. However, the invention of ‘hunmin jeongeum’ also led women to participate in translating works of Buddhist scriptures, Chinese classics and fictional narratives. At the same time, they developed ‘Kasach’e’, a traditional Korean poetry, to express the sorrows and joys of the lives of women's.

In 1894, many foreign literatures from Great Britain, Russia, France, the United States and Germany were translated to Korean, pushing the country to absorb foreign culture and experience a sociopolitical ‘change’. One of th change occurred among women. During the time when Korea was threatened by Japanese colonial domination, translated texts from the western countries encouraged women to participate in patriotic activities.

One of the translated texts was The Story of a Patriotic Lady(1907), the book about Joan of Arc, which was published with the translated title Aeguk Puinjon. The book presented a new female model of ‘a woman as a national heroine’, and thereby gave the Korean women a new duty to participate in saving the nation from foreign aggression.

Consequently, the traditional feminine virtue of the patriarchal society faded with the new ideal of ‘feminine sacrifice’ for the country. From the 1920s to 1930s, translation of foreign works introduced the ‘New Woman’ ideal to the Korean society, which created the new Korean term of “Sinyeoseong” to refer to women who received modern and western-style education.

The translation of Ellen Key’s Love and Marriage(1911) and Henrik Ibsen’s A doll’s house(1879) introduced unprecedented concepts to Korean women such as freedom of choice in love and marriage, breaking away from the oppression posed on women and seeking for new possibilities for women’s lives other than being obedient wives. Hence, a change in women’s identity and their perception was gradually taking place in Korea due to the power of translation. A country that once used to be strictly in the boundary of Confucianism and patriarchy embraced a foreign ideology through translation, and as the new ideology spread, people started to question about the womanhood in Korea.

Back to topThe mpact of Hybridization: The ew Female Identity in Korean Translation

Hybridization is defined as “the ways in which forms become separated from existing practices and recombine with new forms and new practices” (Rowe and Schelling, 1991). The general meaning of hybridization is a “cross-category process”; “the mixture of phenomena which are held to be different, separate” (Pieterse, 2003).

The traditional womanhood became ‘separated from existing’ patriarchal Korean society, and ‘recombined with new forms’, in this case, the feminism ideology from the western countries. The Korean society was different and separated from the notion of feminism or shouting female equality. However, in the frame of globalization, the interaction between the Korean society and western feminism through the medium of translation provoked the hybridization of the two significantly different cultures. This, as a result, produced the new hybrid identity of Korean women, women as equal as men, and this transnational female identity influenced the whole Korean society on how to critically view the gender issues in Korean translation.

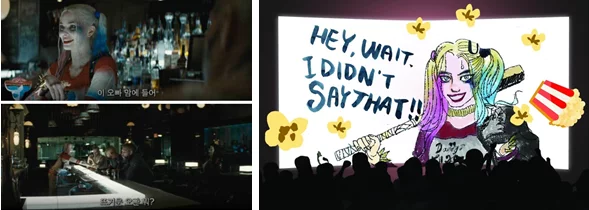

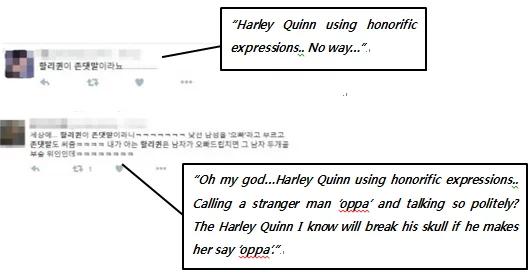

In 2016, the trailer of film Suicide Squad aroused criticism regarding the subtitle that used sexist expressions for the lines of Harley Quinn. This stems from the ‘honorific expressions’ in Korean language. That is, unlike English, there are certain words and expressions in Korean that a person must use to show respect and politeness to the listener. Simply put, while students can just say “hello” equally to their friends, teachers and grandparents in English, there is a strict line between talking to friends and talking to teachers or grandparents in Korean. Influenced by Confucianism, respect and politeness towards the elderly is considered as the most important virtue to Koreans.

However, this Confucianism and emphasis on politeness has especially pressured women. The Confucian idea of the ‘predominance of man over woman’ prevailed in the past, which pushed women to speak politely by using honorific expressions to men. Although times have changed, the idea seems to be still embedded in Korean translation.

The character of Harley Quinn in the film is just an ‘equal’ member of the suicide squad who actually should not show any respect to others according to her original character set-up. However, the Korean subtitle that used the honorific expressions like “-yo” at the end of the sentences or words such as “oppa” (puts her in a lower status compared to other male characters) changed her into a more polite and submissive character.

Nevertheless, it is important to note the ‘change’ in the Korean society, the criticism towards such issue. A Korean dubbing artist Sora Yoon commented on Twitter

“I have been doing this work for 30 years, and this is an issue that I have always experienced. It’s really funny that when the two become lovers, only the man starts to talk down. Even when there is absolutely no difference in the original English lines…”

The Korean fans of DC comics and other viewers of the trailer also criticized the subtitle, as well as a boycott movement of the translator on Twitter. As a result, the subtitle was modified in the actual film. Koreans now feel the wrongness when they see any sexism in translated texts because the thought that ‘women should be treated equally’ is established in their minds due to the influence of western feministic ideology. They also feel the wrongness about the unreasonable traditional Confucian idea about women. The Korean society is undergoing a long-term shift to the global and transnational perspective towards women, keeping keen eyes on the outdated sexist ideas along with meaningful criticisms. Consequently, the traditional Confucian ideas can no longer fit into Korean translation.

Back to topKorea in the 'translated worlds': Keeping the gender hierarchy 'invisible' in Korean translation

The feminism ideology brought from the western world that became incorporated in the Korean language (which itself is a highly hierarchal language) is a very unique form of hybridization: the very conflicting two have combined together. Feminism is one of the framework theories that influenced all areas of societies, and the patriarchal society was not an exception. Gradually, it settled in Korea, and has made women 'visible' in the translation, while turning the gender inequality 'invisible'.

At this point, it seems important to stress once again that globalization is not new and is not a short-term process. The interaction of translated texts that introduced the foreign feminist ideology and ignited the change in Korean women occurred decades of years ago and still is an ongoing process of today. The globalization of feministic ideas empowered women in Korea, but as the current globalization era provides numerous types of translation medium and surrounds us with translations - subtitles or dubbings of dramas, movies, entertainment television programs and advertisements, or translations on Facebook, Twitter and Youtube - it seems even more important to consistently monitor and be alarmed for any words of sexism in Korean translation. `

After all, “the globalization of culture means that we all live in ‘translated’ worlds" (Simon, 1996).” The gender hierarchy did not entirely vanish in Korean translation, but rather 'hidden' from the surveillance and criticism of people. The society has to keep on monitoring, or the hierarchy will build up in the language again. The responsibility is solely on the people of the Korean society who watch and read translation. "You cannot change any society unless you take responsibility for it, unless you see yourself as belonging to it and responsible for changing it" (Boggs, 2005).

Back to topReferences

Harewood, Adrian & Keefer, Tom. (2005). Revolution as a New Beginning: an Interview with Grace Lee Boggs. Upping the Anti.

Hyun, Theresa. (2004). Writing Women in Korea: Translation and Feminism in the Colonial Period. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Rowe, William & Schelling, Vivian. (1991). Memory and Modernity.London and New York: Verso Books.