Exploring the Sublime in Faroese Art and Culture: Nature, Tradition, and Aesthetic Experience

This paper delves into the Faroe Islands' sublime landscapes, examining the impact of art on certain perspectives, exploring the controversial tradition of pilot whale hunting, and prompting reflection on identity and humanity's connection with nature.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Nestled in the Nordic Region, the Faroe Islands (Føroyar in Faroese) is the smallest country in the area, with a population of fifty thousand people scattered across seventeen tiny islands. The history of the Faroe Islands is blurry because the governments of Norway and Denmark would fight over its possession. However, Denmark officially retained possession of Føroyar in 1814, which is also the case today . Because of their complicated past, Faroese people have long struggled with their identity and sense of belonging, which iswhy they highly value their art and culture.

When the Faroe Islands were still forming as a country back in the 19th century, art started having an important role in empowering locals by validating their experiences and fostering a sense of belonging and pride in their identity. Nature has always been present in Faroese art.From landscapes, oceans,and animals, to rocks and stones; there is something unique and empowering about the wild and magnificent universe of the islands. Another aspect of Faroese life that appears in the art, however, has been highly criticized for being unethical, namely,the annual pilot whale hunting tradition of locals.

In this paper, I want to delve deeper into the art, nature, and traditions of the Faroe Islands and discuss the feelings of sublimity that this culture evokes. Moreover, I want to explore how the notion of the sublime, with its long history in literature, philosophy, and the arts, can be used to understand the complexity behind the pilot whale hunting tradition. Prominent intellectuals such as Immanuel Kant, Edmund Burke, and some more contemporary ones such as Terry Eagleton and Alan McNee, have expressed different understandings of what we call sublime.This has advanced our current knowledge of aesthetic experiences and how they can be used to challengeour perceptions and thoughts on sophisticated matters. For the purpose of this research, I will be using visual rhetoric to analyze Faroese art, as well as cultural analysis when it comes to understanding the traditions of the Faroese people (føroyingar in Faroese).

Back to topThe Sublime in Faroese Landscapes

The Faroe Islands are home to scenery that inspires a deep sense of amazement and awe. As far as artistic depiction goes, two particular Faroese landscape paintings - one of a mountain and one of the ocean - provide compelling evidence of the sublime's encapsulation. The first example I want to discuss in this section is "Terrible Storm" (1942) (figure 1) by Niels Kruse,which is one of the oldest paintings in the national art gallery of Tórshavn. As a second example, I have picked a more contemporary work:Sigrun Gunnarsdóttir's "The Mountain" (2010) (figure 2), which, even though it is not as realistic as “Terrible Storm,” it still portrays overwhelmingly the vastness of Faroese mountainous landscapes.

Back to top

Conceptualization of the Sublime

Firstly, the paintings portray the formlessness and vastness of nature, where the boundaries between the ocean, sky, and land blur. This unbounded formlessness is what, according to Immanuel Kant, differentiates a painting from being beautiful or sublime. In Kruse’s “Terrible Storm”, the furious and forceful waves that chaotically move on the canvas puzzle the viewer’s perception of the direction of the defenseless, tilted boat. This technique that Kurse used in the painting creates this incomprehensible feeling of the unbounded formlessness that makes it sublime. The sublime is found in formless objects offering unboundedness, whereas beauty is connected with objects with defined forms or boundaries. Sublime art defies conventional ideas of artistic representation by capturing immensity, enormity, or the inexplicable.

The paintings of Kruse and Gunnarsdóttir serve as a conduit for viewers to recognize their own limitations in the face of nature's raw power.

Furthermore, specific elements of the two artworks induce feelings of threat and danger, such as the unstable boat in a storm in Kruse’s painting or the portrayal of immense mountains overshadowing human presence, reflecting the insignificance of humanity in the face of nature's might as observed in Gunnarsdóttir’s “The Mountain.” Danger and threat are another predisposition for reaching a state of sublimity, according to Edmund Burke. However, he highlights the need to distance oneself from the eye of the danger to be able to access this state. "When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight and are simply terrible; but at a certain distance, and with certain modification, they may be, and they are delightful" (Shaw, p. 74). The sublime effect arises when the imagination fails to impose a form on the phenomena encountered, creating a disconnect between what is perceived and the capacity for rational understanding. This disconnect contributes to the sublime effect.

Back to topThe Dynamical Sublime

In exploring Faroese landscape paintings through the lens of the dynamical sublime, the narrative deepens, encompassing our human response to the overwhelming forces of nature. As articulated by Kant (in Shaw, 2017, chapter 4), the dynamical sublime transcends the object's inherent qualities; instead, it resides in our perception and emotional response to nature's might. Within the context of these artworks, the dynamical sublime emerges as an appreciation of our vulnerability amidst the sublime natural landscapes. The paintings of Kruse and Gunnarsdóttir serve as a conduit for viewers to recognize their own limitations in the face of nature's raw power. The turbulent seas, towering cliffs, and tempestuous storms depicted in their artworks provoke a sense of insignificance, prompting viewers to acknowledge their frailty against nature's overwhelming forces.

However, amidst the portrayal of vulnerability, the dynamical sublime also instills a sense of empowerment. Kant's notion of raising the soul's fortitude beyond its usual range resonates within these artworks. They allow viewers to discover an inner resilience—an ability to resist that transcends conventional definitions. The confrontation with nature's seeming omnipotence encourages viewers to contemplate a different kind of courage—an acknowledgment that despite our inherent weaknesses, a latent strength exists within us, empowering us to confront nature's grandeur.

In Kruse's "Terrible Storm" and Gunnarsdóttir's "The Mountain," the dynamical sublime manifests through the portrayal of a perceived struggle between humanity and the formidable natural elements. The works elicit emotions of both awe and vulnerability, encouraging viewers to confront their sense of awe-inspiring dread in the face of nature's forces. Moreover, the dynamical sublime within these artworks resonates deeply with the Faroese culture's historical narratives of resilience and adaptability. The recognition of human vulnerability within the sublime landscapes echoes the cultural ethos of acknowledging nature's might while embracing the resilience to adapt and thrive amidst its challenges.

In essence, the dynamical sublime, as articulated by Kant, permeates these Faroese landscape paintings. They serve as visual narratives that transcend the mere portrayal of nature's grandeur—they invite viewers on a journey of self-discovery, awakening a paradoxical realization of both vulnerability and inner strength. These artworks become mirrors reflecting the intricate dance between human fragility and the awe-inspiring might of the natural world, resonating deeply with both cultural narratives and individual mentalities.

Back to topFaroese Sublime Traditions and Cultural Practices

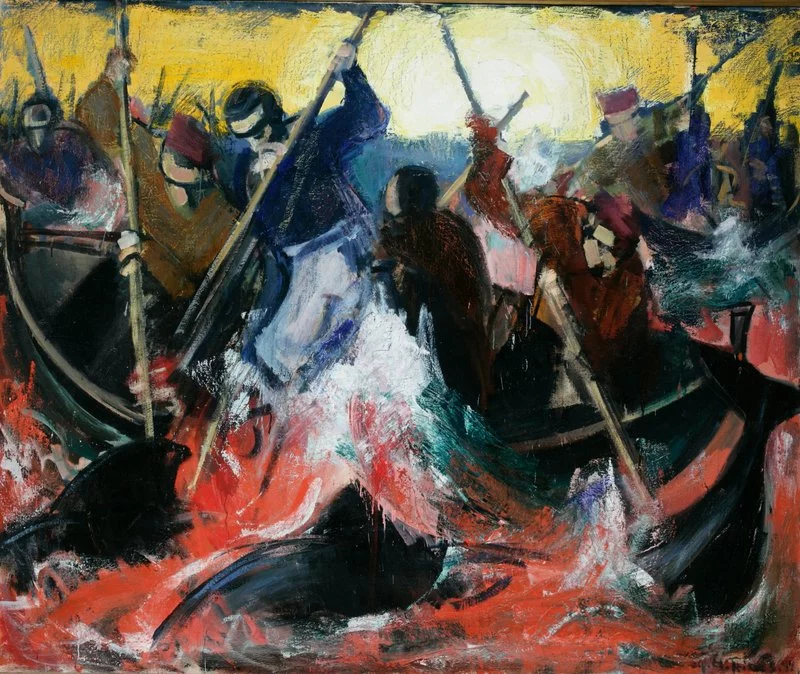

Pilot whale hunting, known as "Grindadrap" (figure 3) in the Faroe Islands, is an annual hunt of around 700 whalesbetween October and June. This long-standing tradition is not just a cultural ritual but also a crucial source of nutrition on the islands, supplying one of the most commonly consumed foods. It is an important component of Faroese culture, deeply rooted in their history and identity. The hunt is a bloody backdrop that becomes a canvas upon which elements of awe, danger, and autonomy merge, altering the experiences of those who participate andengaging the imaginations of those who witness this age-old cultural practice.

Embodying the Sublime

In their annual pursuit, the Faroese whale hunters embody the essence of Eagleton's reflections (Eagleton, 2005) on the sublime within the context of Greek tragedy. Through their commitment to this tradition, the hunters personify a narrative that resonates deeply with this theatrical essence of Greek tragedy. A recurring motif in tragedies links existential concepts such as evil, sacrifice, and choice between life and death to the sublime itself. In a similar vein, Faroese whale hunters face an annual choice imbued with existential weight—the success of the whale hunt determines the community's survival for the upcoming year. Their participation in the hunt intertwines elements reminiscent of tragic heroes. The engagement in this tradition encapsulates Eagleton's concept of the sublime—a convergence of existential choices, encounters with awe and terror, and contemplation on life and death.

Eagleton underscores the significance of terror and awe in broadening perspectives on life and mortality. For the whale hunters, engaging in the perilous hunt amidst the tumultuous seas evokes encounters with fear and awe. The daunting scale of the task, the unpredictability of the sea, and the inherent danger in the hunt provoke intense emotions. This confrontation with elements of nature induces a sense of horror, compelling the hunters to contemplate life's fragility and purpose. Eagleton's proposition that experiencing terror prompts questioning of societal norms resonates with the hunters' reflection on survival and life's deeper meanings—a sentiment aligned with Kant's notion of the sublime empowering individuals to rationalize extraordinary experiences as objects of reason (Shaw, 2017, p. 10).

Back to topWitnessing and Experiencing Scenes of the Sublime as a Community

The hunt for pilot whales embodies a complex interaction between danger, tradition, and the sublime, not only for those who participate in the ritual but also for those who witness it. Burke's sublime concept, founded on fear and remoteness, takes on color when viewed from an elevated viewpoint, such as at the top of a mountain hill, where observers are usually found. They have a unique vista positioned atop the peaks that put them in close proximity to the inherent hazards of the hunt while also positioning them as witnesses to the seriousness of death amidst the grandeur of nature.

The Faroese sublime, which is deeply woven into art, culture, and tradition, encourages a reflection on the complex interactions between humans, nature's grandeur, and the shifting narratives that define Faroese identity and impressions of the natural world.

McNee's assessment of the haptic sublime in mountaineering resonates strongly here. He defines it as an experience of mountainous terrain when the person is in intimate bodily contact with the environment; at times this can be frightening and painful, at other times it can be thrilling and fulfilling, but it always involves some sort of transcendent experience brought about by physical closeness (McNee, 2016). The hiker's experience reflects the haptic sublime, highlighting risk and the mountaineer's intimate interaction with the sublime item. Thus, witnessing the hunt becomes a sensory experience, combining the physical and mental faculties required to contend with nature's raw elements and the rituals of the hunt.

Furthermore, these traditions are more than just individual experiences; they act as intermediaries for communal connection. The social aspect produces a shared sense of the sublime, inextricably linked to collective identities and perceptions. A community not only strengthens its links to tradition by experiencing the hunt collectively but also defines its collective concept of the sublime. This shared experience in the face of danger and the forces of nature becomes a pillar of collective identity. In the context of the pilot whale hunt, the intertwining of risk, tradition, and the sublime illustrate humanity's delicate relationship with the materiality of nature and the nuanced ways in which communities collectively engage with and interpret these experiences.

Back to topContemporary Faroese Art and Ecology

Contemporary Faroese artists have explored the concept of the sublime in a variety of ways, combining traditional mediums with avant-garde approaches. "Whale-War” (2019( by Edward Fuglø (figure 4 ), for instance, is a notable illustration of this engagement. The artwork resonates with Lyotard's concept of the sublime, which is tied to avant-garde art, in which pieces challenge conventions and shatter expectations, creating experiences that defy simple interpretation or absorption (Shaw, 2017, p. 184). Fuglø's installation raises awareness of the Faroese pilot whale hunt by transforming 32,000 toy soldiers into a life-sized representation of a pilot whale. This unique artwork quickly captures the viewer's attention not only because of its size but also because of the sounds of whale hunting sceneries that one can hear when in proximity with the artwork, which is a strong artistic method for fostering reflection.

The issue at hand that creates a controversial debate is the questionable benefits of whale hunting. On one hand, Faroese society is trying to underline that Grindadrap is not the ocean's biggest problem (it has been more and more regulated thesepast years) and that it actually balances out massive hunting on the consumption of salmon. Faroese salmon is the biggest and most profitable export value of the islands (Joensen, 2023) and it is enjoyed by masses of people in Western countries.The pilot whale meat is less popular for export and thus is mainly consumed by Faroese throughout the year. On the other hand, animal welfare activists strongly critique this tradition and boycott the Faroe Islands online, advocating for people to stop visiting the country. In June 2023, a “Don’t Visit Faroe” campaign was launched, and Maissa Rababy, who is part of this campaign, advocated for the following: “We're hoping many supporters can join us as we try to encourage people to halt their visits to the Faroe islands and put pressure on the Faroese government to ban hunts once and for all”(Askew, 2023).

“Whale-War” becomes a crucial avant-garde installation that invites the evaluation of the Grindadrap tradition and shows a different perspective on it by trying to fight against the extreme, rushed accusations from animal welfare campaigns such as “Don’t Visit Faroe.” According to Birgit Schneider, “The subject of climate research (which also involves the waters), media reporting and politics - emerges at the intersection of global and metrological networks that collect climate data and merge it into an abstract concept” (Schneider, 2021). Perhaps this merging into one vague concept is the reason why activists rush to their conclusions about the negative effects of whale hunting on the climate without hearing the Faroese voices. Art and environmental concerns carry a political dimension that becomes common ground for closing this gap. Schneider argues that art has the power to transform the unimaginable into comprehensible forms, and this intertwines with the main idea of Edward Fuglø's work “Whale-War.” “Ultimately the gallery wishes for Whale War to inform about the grindadráp, hopefully resulting in a more constructive dialogue and nuanced critique” (Listasavn Føroya, National Gallery). Schneider's viewpoint and Fuglø's artwork highlight art's transformational power, displaying its ability to foster debates and interpretations that cross conventional boundaries. Both highlight the importance of art in facilitating varied understandings of complicated topics such as the climate catastrophe and the link between culture, tradition, and environmental concern.

Back to topConclusion

The Faroe Islands are an array of unique landscapes and deeply rooted customs that provide an ideal canvas for exploring the sublime. This fusion of art, legacy, and environment elicits feelings of awe, vulnerability, and strength in the Faroese society. Artistry capturing the majestic spirit of wide, broad landscapes exceeds conventional creative norms. This investigation goes beyond aesthetics, connecting with cultural rites such as the pilot whale hunt and combining existential decisions with experiences of wonder, dread, and reflections on life and mortality. Furthermore, these sublime manifestations do not occur in isolation; they form social relationships and shared perspectives. The pilot whale hunt becomes a sensory oneness, promoting a collective understanding of danger, tradition, and the interplay of the sublime's elements. Faroese contemporary art, such as Edward Fugl's "Whale-War," connects with the problematic traditions on the islands to stimulate conversation and examination. Such works go beyond mere depiction to serve as dialogue venues that bridge the gap between local traditions and global ecological challenges. Finally, the Faroese sublime, which is deeply woven into art, culture, and tradition, encourages a reflection on the complex interactions between humans, nature's grandeur, and the shifting narratives that define Faroese identity and impressions of the natural world.

Back to topReferences

Eagleton, T. (2005) States of Sublimity, in: Holy Terror, Oxford: OUP 2005, pp. 42-67

Fuglø, E. (2019) Whale-War. National Gallery Listasavn Føroya, Torshavn, Faroe Islands.

Gunnarsdóttir, S. (2010) The Mountain. National Gallery Listasavn Føroya, Torshavn, Faroe Islands.

Joensen, H. (2023). Exports of goods: Statistics Faroe Islands. Exports of goods | Statistics Faroe Islands.

Joensen-Mikines, S. (1944), Grindadrap, National Gallery Listasavn Føroya, Torshavn, Faroe Islands.

Kruse, N. (1942) Terrible storm. National Gallery Listasavn Føroya, Torshavn, Faroe Islands.

Listasavn Føroya, The National Gallery of the Faroe Islands Listasavn Føroya.

McNee, A. (2017). The New Mountaineer in Late Victorian Britain: Materiality, Modernity, and the Haptic Sublime. Springer.

Shaw, P. (2017). The sublime. Taylor & Francis.

Schneider, B. (2021) Sublime Aesthetics in the Era of Climate Crisis? In: T.J. Demos, E.E. Scott, S. Banerjee. The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change