Digital Facework on Instagram: The Celebrity, Aspiring Lawyer and Social Justice Advocate Kim Kardashian

This study explores Kim Kardashian’s digital facework on Instagram as she constructs her face adding the new layers of an aspiring lawyer and social justice advocate. By analysing her posts and audience engagement, it highlights the interplay between staged authenticity, commodification of social advocacy and platform’ affordances’ power within digital economy.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

On this page

- Face & Facework in Social Interaction

- Digital Interaction: Audience Design, Context Collapse and Context Design

- Platform Dynamics: Algorithms, Power and Digital Economy

- The Commodification of Authenticity on Social Media

- Research Questions, Data Collection and Analysis

- Kim Kardashian on Instagram

- From Celebrity to Law Student: Staged Authenticity or Backstage Insights?

- From Celebrity to Social Justice Advocate - And Back: Navigating Multiple Faces & Audiences

- Social Advocacy, Branding and Strategic Social Media Use

- User Engagement, Facework and Platform Economics

- Conclusion

- References

Kim Kardashian’s Instagram activity offers an interesting lens to explore the construction of digital facework. Navigating through her established faces as a celebrity and businesswoman, Kardashian strategically attempt to incorporate new layers to it: the aspiring lawyer and social justice advocate. This paper examines how she uses Instagram to balance facework and navigate her diverse audiences. By analysing her posts and users’ engagement with it, the paper explores the commodification of staged-authenticity and social advocacy within digital economy, highlighting how platforms influence interactions and facework.

Back to topFace & Facework in Social Interaction

Goffmann’s (2003) concepts of face and facework are integral to understanding social interactions. "Face" refers to the positive social image a person attempts to project (Goffmann, 2003). This image is not necessarily a reflection of the “true” self, but rather an idealised persona shaped by mutually agreed social norms of a community (Virtanen & Lee, 2022). In a dramaturgical sense, individuals adopt roles and act accordingly, aiming to maintain their face during interactions (Goffmann, 2003). Interactions can be seen within the frontstage and backstage behaviour frame. In the frontstage, individuals perform publicly adhering to social norms, and in the backstage, privately, people are free of these norms, behaving as they want (Merunková & Šlerka, 2019).

However, face is not solely the result of personal effort, but is mutually granted during an interaction, highlighting its intersubjective nature (Scollon & Scollon, 1995, as cited in Virtanen & Lee, 2022). This becomes more evident with the notion of the interaction order, which refers to people’s common attempt to maintain balance and stability in their social interactions based on mutually agreed conventions (Persson, 2018). Interaction order is seen as a mutual balancing act emerging between the ritualisation of interactions and vulnerability, creating a “temporarily working consensus” (Persson, 2018, p.26).

These social norms where face construction and interaction are based on are not universal. Instead, they are heavily context based and chronotopically situated (Goffman, 2003). This can lead to losing, maintaining or gaining face depending on the meta-reflectivity of each person and their evaluation of the interaction . The act of framing one’s behaviour as consistent with their social face is called facework and “serves to counteract ‘incidents’—that is, events whose effective symbolic implications threaten face” (Goffman, 2003, p. 8). However, as Virtanen and Lee (2022) mention, facework does not consist solely of attempts to save and protect one’s face, it also includes acts such as face-enhancing.

Back to topDigital Interaction: Audience Design, Context Collapse and Context Design

Goffman’s framework was developed for face-to-face interactions, but digital spaces introduce new ways of examining interaction. Digital interaction has a non-synchronous nature (Maly, 2022), characterized by its persistence (since interactions can be archived), searchability (both regarding content and people), replicability (as one cannot know if the content they are seeing is original) (Merunková & Šlerka, 2019) and shareability (through having the ability to share content with large audiences) (Kaul & Chaudhri, 2018). These features, as well as each platform’s own affordances, change the way facework is conducted on multiple levels.

A significant shift in the facework of (digital) creators often involves “audience design” (Bell & Gibson, 2011) and “context collapse” (Kaul & Chaudhri, 2018). Individuals adapt their behaviour based on their audience (Bell & Gibson, 2011). However, digital platforms complicate this process because users often create their content based on their diverse imagined and invisible audience (Marwick & boyd, 2011, as cited in Kaul & Chaudhri, 2018). Users tend to create and share content based on what they think as their “imagined”, anticipated audience (Merunková & Šlerka, 2019). However, users often cannot control who might come across and interact with their content, given the previously mentioned features of digital interactions, creating “invisible audiences” (Merunková & Šlerka, 2019).

As platform’s diverse networked audiences are often invisible and lack social and spatial boundaries, it becomes even more difficult to control the context of the interaction, often leading to "context collapse" (Kaul & Chaudhri, 2018). However, the notion of the context is not stable, but fluid and constantly re-constructed through discursive interaction practices. That’s why Tagg and Seargeant (2021) introduced the term “context design” which aims to explore “how, at the moment of interaction, people’s ideologically framed and unfolding understandings of a particular site and its social dynamics both shape their communicative behaviour and guide their evaluation and response to others”((p. 7).

Ultimately,they highlight the connection between media and language, using the term “language/media ideologies” to emphasize that communication choices in online spaces and ways of interpreting these are influenced not only by semiotic norms and ideologies, but also by how users perceive and use platforms (Tagg & Seargeant, 2021).

Back to topPlatform Dynamics: Algorithms, Power and Digital Economy

Digital platforms are not neutral intermediaries of interactions, but active participant in shaping them (Maly, 2024). Platforms function as algorithmic actors, influencing content production through affordances, community guidelines and algorithmic designs . These mechanisms also determine what content is visible to which users , monitoring interactions and sociality (van Dijck, 2013, as cited in Maly, 2024). Platform cultures emerge from these design choices, creating rules and norms that steer or directusers’ behaviour . Conformity to these norms is often rewarded with greater visibility, while deviation may result in reduced reach (Maly, 2023). Social media algorithms are deeply ideological since they “produce a largely invisible and implicit metadiscourse on our interactions and that metadiscourse not only categorizes us, it sorts the information and interactions we will get to see and the ones that will never reach our newsfeeds. As a result, we see that humans behave and interact in specific ways and not in others.” (Maly, 2022, p. 8)

The importance of power in digital platforms can also be examined through the lens of digital economy (Maly, 2024). In this framework, the means of production have shifted, with value being derived from digital interactions rather than traditional labor. Platforms encourage user activity through affordances like metrics (likes, comments, and shares), which facilitate data extraction while being framed as “meaningful interactions” (Maly, 2023). User interactions, even those as simple as reaching one’s feed and scrolling away, generate data that platforms monetize and capitalize on (Maly, 2022). The article further reveals tha this leads to social media algorithms being seen “as socio-cultural assemblages – producing normativities, and it is these normativities that co-create new communicative economies” ( p. 3).

Back to topThe Commodification of Authenticity on Social Media

As Jerslev and Mortensen (2016) note, celebrities are an ongoing performance act where audiences help complete it (Ma, 2022). Within digital platforms, celebrities deliberately share content framed as personal part of their (everyday)life, to create a sense of intimacy (Gaden & Delia, 2014). This fosters parasocial relationships where audiences feel personally connected despite the interaction’s one-sided nature (Dekavalla, 2022). This authenticity, however, is staged and aims to support the influencers’ personal brand, transforming their public persona into a commodity for consumption (Jerslev & Mortensen, 2016).

Therefore, public figures strategically share what appears to be private, behind-the-scenes content, inviting audiences to interact with it (Dekavalla, 2022). By interacting, whether as accepting or rejecting the person’s face through deliberate actions such as (not) liking, or leaving a positive/ negative comment, users produce data which translates into profit for the platform and the celebrity, but also at the same time users’ activity becomes part of their facework as it adds to the construction of their face (Merunková & Šlerka, 2019).

Back to topResearch Questions, Data Collection and Analysis

This paper explores Kim Kardashian’s efforts to present herself as an aspiring lawyer and social justice advocate on Instagram. The research questions driving this paper are:

- How does Kim Kardashian use facework on Instagram to promote her persona as an aspiring lawyer and social justice advocate?

- How is this effort interpreted by users in the comments section?

Using a digital ethnographic approach (Kaur-Gill & Dutta, 2017), I observed Kim Kardashian's Instagram activity for two months. Data collection began with screenshots of older relevant posts, starting with her December 2021 post announcing she passed the baby bar exam. In this paper, I will focus on the close analysis of two lawyer-related posts, four posts, and two stories on social justice advocacy. To analyse audience reception, I examined the first 10 comments of each post from the "For you" display option, using a research-specific account to limit algorithmic influence. Data was last accessed on 08/01/2025, with user anonymity ensured, except for Kardashian as a public figure.

The analysis focused on micro-level details, examining the (verbal and multimodal) semiotic choices, platform affordances and their implications. Posts and comments were analysed as social interactions within broader sociotechnical and ideological contexts. It is important to mention that when referring to Kim Kardashian’s social media content, I’m referring also to her social management team, which might have co-produced content through media managing.

Back to topKim Kardashian on Instagram

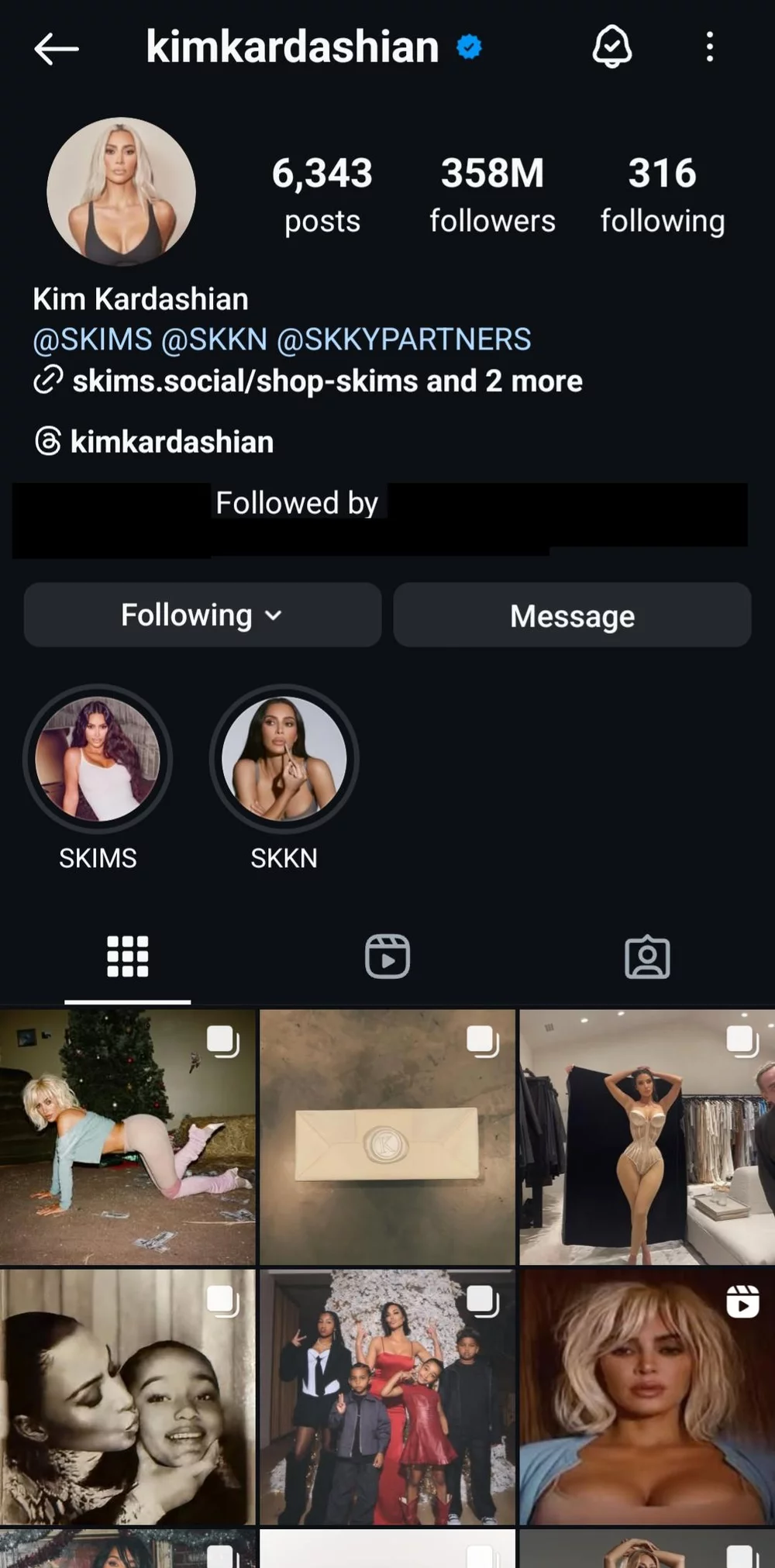

Kim Kardashian is a globally known celebrity, businesswoman and influencer. She became largely known through the reality TV-show Keeping Up with the Kardashians. Additionally, she has created a specific image of herself, connecting it to and influencing a dominant feminine beauty ideal (Ma, 2022). Over time, she built her personal SKIMS clothing brand and SKKN skincare brand.

When having a quick first look at her Instagram page, we see that her followers expand to 358 million (Last updated: 08/01/2025). The blue checkmark profile verification signifies her status as a public figure, reinforcing her credibility as backed by the Instagram platform. The bio of her profile consists of the accounts and links to her businesses. Similarly, her businesses are the only thing she “highlights” on her profile via the big "story"-circles below her bio. By examining the image-based posts displayed on the profile, we can mainly identify posts related to her businesses, family, media and celebrity life. However, occasionally there are posts that refer to her journey of becoming a lawyer and her actions as a social justice advocate. Therefore, her Instagram can be seen as a performative space where, through digital facework, her various faces are managed.

Back to topFrom Celebrity to Law Student: Staged Authenticity or Backstage Insights?

On December 13, 2021, Kim Kardashian announced via Instagram that she passed the baby bar exam, formally known as the First-Year Law Student’s Examination. This exam is required in California for students pursuing a legal career through non-traditional educational routes, like unaccredited schools, to qualify for the main bar exam to officially become a lawyer. This announcement indicates the starting point of a deliberate facework aimed to introducing a new layer to her face: the aspiring lawyer. This post and its accompanying text highlight how she tries to leverage discursive semiotic elements and algorithmic platform strategies to not completely reframe her face but to navigate the celebrity-aspiring lawyer intersection.

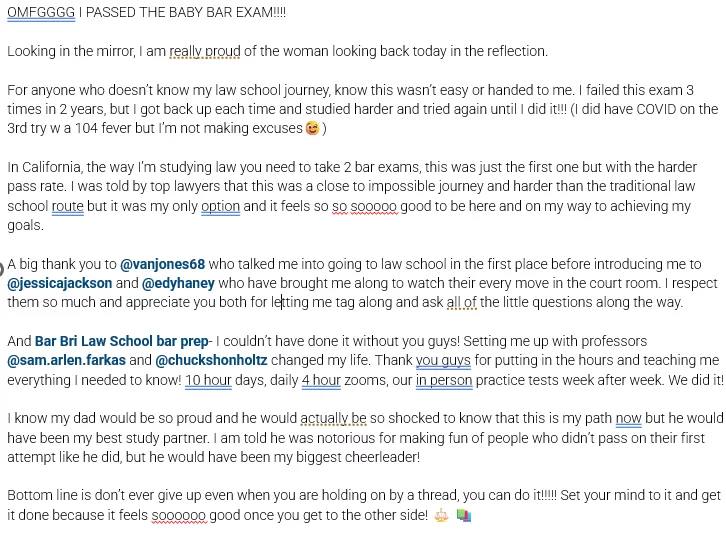

Kardashian follows the platform’s culture, where sharing intimate information with large audiences is normalized and even expected, especially for public figures (Dekavalla, 2022). Her post serves as an example of staged intimacy, where public figures disclose personal struggles to create the illusion of vulnerability, relatability and accessibility (Gaden & Delia, 2014). The accompanying text consists of a carefully crafted narrative design to draw follower into her new journey. Language plays a key role in this process. Emotional language and dramatic capitalization, extensive use of exclamation marks and elongated letters, e.g. “OMFGGGG I PASSED THE BABY BAR EXAM!!!!”, create a sense of spontaneous reaction and shared celebration. Additionally, her emotional reference to her late father, and renowned lawyer, “I know my dad would be so proud”, humanises her to her audience, while legitimising her ambition as following the family’s legacy. Similarly, mentioning her struggles and failures (e.g. “I failed this exam 3 times”) presents her as relatable and not very different from an “average” person. She tries to highlight her resilience, as a face-enhancing strategy (Virtanen & Lee, 2022), through explicitly stating that she “studied harder and tried again until I did it!!!” and aims to prove her hard-work by quantifying it “10-hour days, daily 4-hour Zooms, in-person practice tests week after week”. This framing of her journey is accompanied by phrases like “Bottom line: don’t ever give up even when you are holding on by a thread, you can do it!!!!! Set your mind to it and get it done because it feels soooooo good once you get to the other side! ⚖️ 📚” promoting aspirational labour discourse, encouraging relentless work to pursue a career where you do what you love (Duffy, 2016).

While many followers might relate to her struggles and draw inspiration from this aspirational discourse, the post highlights existing power inequalities emerging from her privileges that would have made it impossible for the majority of her followers to follow the same route. These privileges include access to prominent lawyer-mentors (“I was told by top lawyers”), elite educational resources (“Bar Bri Law School bar prep”) and her family’s legacy. Her journey, while framed as “self-made” (“wasn’t easy or handed to me”), relies on material and symbolic capital inaccessible to most of her followers. Thus, she reinforces existing inequalities, framing her success as a product of personal effort rather than emerging from socioeconomical structures and advantages.

The choice of a high-end glamorous photograph reflects her socioeconomic status mentioned previously. Through stating that “Looking in the mirror, I am really proud of the woman looking back today in the reflection,” indicating a careful blending of the text with the image and her celebrity status with her “authentic” ordinary self. This post indicates the commodification of authenticity (Jerslev & Mortensen, 2016). Personal milestones are not just shared and celebrated but also strategically monetized. Mobilizing Instagram’s affordances, she tags prominent lawyers, professors and exam preparation school, not just expressing gratitude but using it as promotional mechanisms embedded within her personal narratives.

Instagram's features enable us to see that the post was edited after its initial publication. Yet, the initial content is inaccessible to viewers. This raises questions about how Kardashian curated and reconstructed the narrative of the post to possibly optimize its impact. The ability to edit a post underscores the performative nature of social media authenticity, reminding us that “genuine” moments are subject to revision. As Maly (2024) notes: “This intimacy is staged, and thus performed, and that influencers do not really give their followers insight into the backstage—they suggest or perform that intimacy and backstage access.” (p.10)

Back to topFrom Celebrity to Social Justice Advocate - And Back: Navigating Multiple Faces & Audiences

Kardashian’s attempt to introduce her new identity as a lawyer is interconnected and supported by her efforts to present herself as an active social justice advocate. As mentioned before, this transition is not a radical and complete departure from her celebrity persona, that could lead to loosing her audience, which follows her for her usual content. Instead, it demonstrates a strategic “context design” (Jerslev & Mortensen, 2016), blending her identities to navigate a diverse, invisible and imagined audience (Marwick & boyd, 2011, as cited in Kaul & Chaudhri, 2018), with as little context collapse as possible (Kaul & Chaudhri, 2018).

More specifically, in her post about visiting the Department of Justice in Washington D.C. to advocate for clemency for incarcerated individuals, she shares pictures that can be interpreted as within influencer aesthetics. For instance, she took a selfie in front of the U.S. flag, making peace sign and a “duck face” with her lips, an online posing trend that she heavily participated in around 2016. By framing the post this way, Kardashian introduces, in a soft and controlled way, her new emerging aspiring lawyer and advocate characteristics next to her established persona, making it more digestible to her diverse followers.

In contrast to the celebratory, spontaneous and emotional tone and writing style of her baby-bar exam post, the text accompanying this post adopts a more serious and calculated style, using frequent punctuation and no emojis or non-standard language. This together with her reference to the (now former) President Joe Biden, indicates that she takes what she is doing very seriously and that her content and audience are not limited to her followers, that follow her for her usual content, but also political figures and policymakers, enhancing the sense of credibility as a social justice advocate and future lawyer. This shift reflects her awareness of different semiotic choices that are seen as appropriate to each context and purpose (Tagg & Seargeant, 2021).

Back to topSocial Advocacy, Branding and Strategic Social Media Use

Her stylistic choices, of wearing a very fashionable, body-hugging outfits reminiscent of her SKIMS clothing brand, should not go unnoticed, especially since it also occurs in setting where these choices are not the norm. For example, during her visit in Pine Grove Youth Conservation Camp, where Kardashians’ posing and clothing choices come in high contrast with the orange uniforms of the incarcerated people.

Wearing her own clothing brand can be seen as commodification of social advocacy and leveraging from the visibility of the posts to implicitly promote it. Therefore, her posts transform advocacy into an extension of her marketable identity, allowing her to maintain relevance in both celebrity/businesswoman and political discourse. While the two might seem unrelated, the overlap is intentional: her “activism” enhances her credibility and depth as a public figure, making her reach audiences that otherwise dismiss her solely as a reality TV star. This credibility in turn enhances her marketable identity (Jerslev & Mortensen, 2016) and benefits her personal brand.

Adding to that, she strategically employs Instagram’s affordances to boost her reach. Hashtags like #ClemencyNow increases the post’s visibility, while making a statement that enhances her role as an advocate. Features like multiple-image posts provide visual narratives that complement her written text and the ability to edit posts allows her to maintain control over her content. For example, she announced that “Starting this week, I will be highlighting some of their important cases on my stories”. By using stories, a feature often seen as ephemeral and casual (Georgakopoulou, 2021), she transforms deeply ideological issues, like clemency, into shareable, bite-sized content, that ultimately commodify the essence of it and create revenue for her through visibility.

Back to topUser Engagement, Facework and Platform Economics

Digital platforms direct and commodify users’ interaction. Metrics such as likes, shares and comments, as ways of generating engagement, are used to evaluate audience reception, functioning as feedback loops (Tagg & Seargeant, 2021) for her digital facework. Positive comments, such as “thank you for all you hard work bby” (In post 2) and “(...) It doesn't matter what financial status we are at, but committing to hard work makes us women that have the same common. Strong women our young generations can look up to. Best wishes Kim on your future goals to pass the Bar, routing for you” (In post 1), indicate an acceptance of Kim’s new face as committed social justice advocate, aspiring lawyer and relatable authentic person.

On the contrary, critical comments like “Alllll that money just to say you did it” (in post 1) and “Tf she know bout politics” (in post 2), show the rejection of the new qualities, or maybe even the maintenance of an already negative impression (Ma, 2022). Commenting enables users to indicate their positionality, simultaneously contributing to their own facework (Merunková & Šlerka, 2019). However, whether their comment indicates acceptance of this newly introduced face, or not, it still generates engagement that translates into visibility and profitable data (Maly, 2022).

Kim Kardashian’s Instagram activity highlights the dynamics of digital facework, where personal branding, platform affordances and audience engagement intersect to construct her face. Through strategic context design (Tagg & Seargeant, 2021), she integrates her established celebrity and businesswoman image with her evolving ones: the aspiring lawyer and social justice advocate. Rather than presenting a radical shift, the facework balances relatability, credibility and marketability, navigating diverse imagined and invisible audiences (Marwick & boyd, 2011, as cited in Kaul & Chaudhri, 2018).

Back to topConclusion

Kim Kardashian's portrayal as an aspiring lawyer is based on staged intimacy (Gaden & Delia, 2014), presenting personal struggles to foster relatability while framing her success as self-made. However, this narrative hides the significant privileges supporting her journey, reinforcing an unequal aspirational discourse (Duffy, 2016). Similarly, while presenting herself as a social justice advocate, she blends influencer aesthetics with advocacy, commodifying social justice into sharable, consumable and profit-generating content (Jerslev & Mortensen, 2016), through platform affordances like hashtags and stories.

At the same time, audience comments act as feedback loops (Tagg & Seargeant, 2021), shaping Kardashian’s facework, but also adding to the commenters’ facework (Merunková & Šlerka, 2019). Some comments indicate the acceptance of this new layer of her face, while other indicate it’s rejection, maintaining the already establish perception of her face. Regardless of its positionality, all interaction is engagement, that reinforces the profit-driven nature of social media platforms (Maly, 2022).

Therefore, Kardashian’s case highlights the evolving dynamics of face construction in digital spaces, where algorithms and platform usage reshape traditional facework. Her facework confirms how social media, as socio-cultural assemblages, dictate their usage, and therefore interaction, commodify it and reinforce the socioeconomic ideologies embedded in platform design (Maly, 2022).

Back to topReferences

Bell, A., & Gibson, A. (2011). Staging language: An introduction to the sociolinguistics of performance. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 15(5), 555-572.

Dekavalla, M. (2022). Facework in confessional videos by YouTube content creators. Convergence, 28(3), 854-866.

Duffy, B. E. (2016). The romance of work: Gender and aspirational labour in the digital culture industries. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 19(4), 441-457.

Gaden, G., & Dumitrica, D. (2015). The ‘real deal’: Strategic authenticity, politics and social media. First Monday.

Georgakopoulou, A. (2021). Small stories as curated formats on social media: The intersection of affordances, values & practices. System, 102, 102620.

Goffman, E. (2003). On Face-Work: An Analysis of Ritual Elements in Social Interaction. Reflections: The SoL Journal, 4(3), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1162/15241730360580159

Jerslev, A., & Mortensen, M. (2016). What is the self in the celebrity selfie? Celebrification, phatic communication and performativity. Celebrity Studies, 7(2), 249-263.

Kaul, A., & Chaudhri, V. (2018). Do celebrities have it all? Context collapse and the networked publics. Journal of Human Values, 24(1), 1-10.

Kaur-Gill, S., & Dutta, M. J. (2017). Digital ethnography. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research.

Ma, Y. (2022, July). Kim Kardashian’s Self-Publishing Stage and Her Audience Imitators. In 2022 3rd International Conference on Mental Health, Education and Human Development (MHEHD 2022) (pp. 1078-1083). Atlantis Press.

Maly, I. (2022). Algorithms, interaction and power: A research agenda for digital discourse analysis.

Maly, I. (2023, June 16). Digital economy and platform ideologies. Diggit Magazine. https://www.diggitmagazine.com/working-papers/digital-economy-platform-ideologies-influencer-culture

Maly, I. (2023, June 16). Reproducing platform ideologies: Do what you like with Gary VEE. Diggit Magazine. https://www.diggitmagazine.com/working-papers/reproducing-platform-ideologies-do-what-you-gary-vee

Maly, I. (2024, November 9). Digital facework and the digital interaction order. Diggit Magazine. https://www.diggitmagazine.com/articles/digital-facework-digital-interaction-order

Maly, I. (2024). Digital Facework, politics and small scandals. Language in Society. doi:10.1017/S0047404524001076

Merunková, L., & Šlerka, J. (2019). Goffman's theory as a framework for analysis of Self presentation on online social networks. Masaryk University Journal of Law and Technology, 13(2), 243-276.

Persson, A. (2018). Framing social interaction: Continuities and cracks in Goffman's frame analysis. Taylor & Francis Group.

Tagg, C., & Seargeant, P. (2021). Context design and critical language/media awareness: Implications for a social digital literacies education. Linguistics and Education, 62, 100776.

Virtanen, T., & Lee, C. (2022). Face-work in online discourse: Practices and multiple conceptualizations. Journal of Pragmatics, 195, 1-6.

Back to top