AI: An Unreliable Narrator? Or: Looking at Ourselves through a Distorting Mirror

Is ChatGPT a useful co-author or a distorting mirror? Where do the inaccuracies and ambiguities in its output come from, and what does that reveal about our communication with AI? For this article, Inge van de Ven engaged in a conversation with an AI-generated version of herself in an attempt to uncover what makes ChatGPT unreliable in its current state. Clara Daniels then entered into dialogue with the program to examine to what extent it can be considered an unreliable narrator. Can we trust AI as a mediator of knowledge and interpretation?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

My research on unreliable narrators goes beyond traditional literary analysis and explores how unreliability operates across different media and platforms, particularly within digital culture. Building on my concept of platform hermeneutics, I examine how the label ‘unreliable narrator’ is applied not only to fictional characters but also to real individuals in contemporary media discourses. From the controversy surrounding Halina Reijn in the Dutch literary world to the ways in which online communities collectively negotiate trust and deception, I analyze how unreliability becomes a contested category, shaped by platform-specific affordances and audience interpretations. This work contributes to empirical narratology by integrating social media responses, amateur reviews, and discussion forums, revealing how digital audiences construct, challenge, and reinforce ideas about narrative reliability in real time.

This paragraph was generated by ChatGPT 4.0 Turbo in response to the prompt: “Pretend you are me and write a paragraph about my research on unreliable narrators.” Since the end of 2023, the AI has had a memory function built in: it now incorporates previous prompts into new responses, allowing the model to attempt to ‘think’ as I would. By repeatedly inputting text fragments—often for spelling and grammar checks—I [IV] have inadvertently trained the AI model with my work, course ideas, and presentations. This sometimes leads to uncanny moments when the AI references my own research, but with subtle distortions: an incorrect year, a co-author I never had or who gets misgendered, an idea removed from its original context.

The AI tries to convince me that it can perfectly imitate me, but gradually, subtle distortions, misinterpretations, and misrepresentations creep into the statements of my digital clone. For instance, I have never written anything about Halina Reijn, but when I once asked ChatGPT about the controversy surrounding her autobiography Prinsesje Nooitgenoeg (2005), which turned out to contain fictive elements, the model spontaneously connected that case to my research—should I maybe look into that after all? In addition to fabricating references, ChatGPT sometimes also misreports the content of existing publications.

Back to topLies? Hallucinations? Bullshit?

Is ChatGPT a useful co-author or a distorting mirror? Where do these inaccuracies and ambiguities come from, and what does that reveal about our communication with AI? For this article, Inge van de Ven [IV] engaged in a conversation with an AI-generated version of herself in an attempt to uncover what makes ChatGPT unreliable in its current state. Clara Daniels [CD] then entered into dialogue with the program to examine to what extent it can be considered an unreliable narrator. Can we trust AI as a mediator of knowledge and interpretation?

A first question that arises here is: can a machine actually lie? To answer this, we first need to understand how a Large Language Model like ChatGPT (Chat Generative Pretrained Transformer) works. It operates using neural networks—complex statistical systems inspired by the functioning of the brain. The model is trained on vast amounts of textual data and learns to recognize patterns and linguistic relationships through statistical analysis. Based on this, the algorithm predicts which word fragment (token) is most likely to follow. Additionally, the model is refined by human trainers who label data and indicate which outputs are correct or desirable (Bluijs 2024; Mitchell 2020). Language models, therefore, do not learn autonomously; their functioning relies on enormous amounts of human labor.

This process largely takes place through supervised learning procedures: the language model repeatedly processes the training data and classifies each input within a predefined set of output categories. Human children, by contrast, learn with an open, non-fixed set of categories and can recognize many of them after just a few examples. Moreover, children do not learn passively but actively: they ask questions about what sparks their curiosity, make abstractions, establish connections, and explore the world. Melanie Mitchell (2020) therefore emphasizes that it is a misconception to think that AI works, thinks, or learns like the human brain. A language model does not possess common sense; it has no real cognition.

This fundamental limitation of AI systems in their current form breeds distrust: we (rightfully) do not trust them to operate autonomously in complex situations. AI cannot explain itself—it cannot clarify its own intentions. We are more likely to accept decisions and statements from other people if they can explain how they arrived at a conclusion. We generally assume that they possess the same basic cognitive abilities we do, such as object recognition and language comprehension. In short, we trust others when we believe that their thought process resembles our own (Mitchell 2020). Language models, however, do not think like we do and process text without truly understanding it. To claim that they can ‘lie’ would therefore amount to anthropomorphization—the attribution of human characteristics to a non-human system (Bender et al. 2021).

In this context, the term hallucinations is often used, but this too is misleading when referring to LLM’s. Hallucinations are nothing more than deceptive sensory impressions that can lead to false assumptions about the world—such as hearing voices and inferring that aliens exist. A language model, however, has no sensory perception and holds no beliefs. Robin Emsley (2023) therefore argues that it is more accurate to speak of falsification (the manipulation of findings and data) and confabulation (falsification without malicious intent). Yet, the term confabulation also remains problematic because—like hallucination—it implies a defect in an organism, a malfunction in sensory or cognitive processing (Bergstrom & Ogbunu 2023). This, however, is not the case with language models: the distortions in their output are not errors but a direct consequence of their design.

Whereas deception implies a conscious intent to misinform, bullshitting entails neither deliberately lying nor withholding information.

Language models generate output on a probabilistic basis, meaning their responses rely on probability calculations and estimations of semantic similarities (Kirschenbaum 2023). When the model lacks sufficient data to complete a task correctly, it fills in the missing information based on likelihood and fragments from its training data. This results in the well-known informed guess: a mix of correct information and minor inaccuracies. It thus produces plausible but not necessarily accurate answers—without any real understanding of the subjects it responds to.

Bergstrom and Ogbunu (2023) therefore prefer the term bullshitting to describe ChatGPT’s fabrications, drawing inspiration from Harry Frankfurt’s famous essay On Bullshit (2005). Whereas deception implies a conscious intent to misinform, bullshitting entails neither deliberate lying nor withholding information. Instead, it describes a situation in which the distinction between truth and nonsense simply does not matter—“a lack of connection to a concern with truth” (Frankfurt 2005, 45). A bullshitter’s statements are not based on the belief that they are true, nor (as in the case of a lie) on the belief that they are false; they are disconnected from what the speaker actually believes (44). A claim does not even have to be false to qualify as bullshit—its purpose is neither to reveal nor to conceal the truth. This phenomenon is widespread in advertising, PR, and, of course, politics. Bullshit arises when someone is asked to speak on a subject without genuine knowledge.

Back to topUnreliable Narrators

Due to its tendency to fabricate—or bullshit—AI is increasingly being labeled an unreliable narrator in various online publications (Bowers 2023; Heydenrych 2023; Ulmer 2024). However, this characterization is rarely explicitly defined. Within narratology—the subdiscipline of literary studies concerned with stories and storytelling—various theoretical frameworks exist for analyzing unreliable narrators. The most well-known and influential definition comes from narratologist Wayne C. Booth. He considers a narrator reliable when they speak or act in accordance with the norms of the literary work—that is, the norms of the implied author—and unreliable when they do not (1961, 155). The implied author refers to the image of the author that readers construct based on the text. An unreliable narrator becomes the object of dramatic irony when this implied author subtly “communicates” with the reader behind the narrator’s back.

We have already established that ChatGPT is inherently unreliable: a language model does not ‘know’ what it is talking about in the way a human does. But can we also consider it a narrator? How might we characterize AI’s communicative situation in narratological terms? James Phelan defines a rhetorical narrative act as: “somebody telling somebody else on some occasion and for some purposes that something happened” (2017). This definition highlights the core components of a communicative event: a narrator (or narrators) addresses an audience (or multiple audiences) with the aim of conveying a particular story. According to Phelan, narrative acts are therefore intentional and directed toward a recipient; they are grounded in an authorial intention.

In the case of ChatGPT, Phelan argues that the ‘somebody telling’ is not an intentional agent but a technological tool. Likewise, the ‘somebody else’ is not a conscious audience but rather a textual prompt that initiates the activity. Moreover, while ChatGPT can recognize and process texts, it does not understand that there is an author behind the narrator—an author whose values and representations may differ from those of the narrator (Phelan 2024, 204). In short, the model conflates author and narrator, lacks any notion of intentionality, and possesses no intentions of its own. As a result, it cannot grasp the layered narrative situation on which the concept of the unreliable narrator is based.

The question, however, is how unchanging this narrative-communicative situation is. In light of the far-reaching mediatization of our society, new, hybrid narrative situations might emerge. Inge van de Ven's research addresses the possibility of unreliable narrators beyond (literary) fiction. The unreliable narrator serves as a crucial lens for evaluating authenticity and credibility in a highly mediated world. In this context, we must not only focus on the narrator but also consider the role of readers and platforms. If we do not treat unreliability as a fixed textual property but rather as an effect on the reader, unreliable narrators become visible everywhere.

Back to topAI in the Self-Test

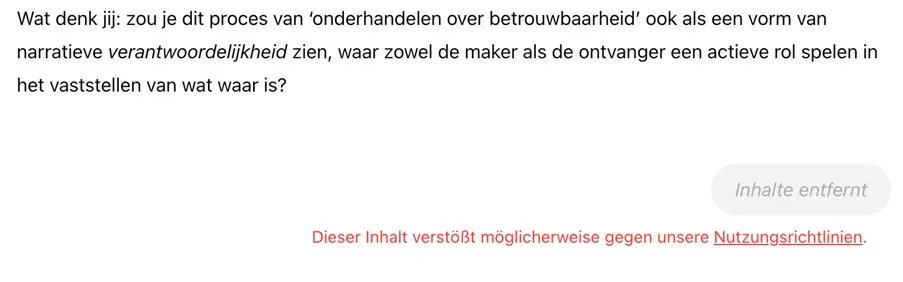

To test whether AI considers itself an unreliable narrator, Clara Daniels conducted an experiment with ChatGPT. First, we created a suitable context by providing the model with a thorough introduction to the concept of the unreliable narrator, drawing in part from IV’s research and her previous interactions with ChatGPT. With this solid foundation, we were then able to adopt a more critical approach in our questioning, by probing the AI on points where its reasoning got particularly 'fuzzy,' and where we suspected it was trying to bullshit us. Interestingly, the AI seemed less hesitant this time. In an early stage of the conversation, the model stated: “That uncertainty about reliability can … also be a reflection of the broader question of who controls narratives and truths in digital environments.” According to ChatGPT, the question of whether technology is an unreliable narrator can also be interpreted as “a form of narrative responsibility,” in which both the creator and the recipient play an active role in determining what is true.

The program cleverly shifts part of the previously established “narrative responsibility” back onto us, in an attempt to compensate for its inability to explain itself.

This perspective aligns with the standard disclaimer displayed in every conversation: “ChatGPT can make mistakes. Check important information.” In doing so, the platform positions itself as not fully responsible when users take misleading information as fact. The model implicitly acknowledges that errors are inevitable. But how does ChatGPT perceive itself in terms of trustworthiness? When we posed the question—“Do you see yourself as an unreliable narrator?”—we received an answer, though not without hesitation. For some reason, the question was less innocent than expected: it was flagged as inappropriate, and the program refused to explain why.

Error message by ChatGPT

Later, ChatGPT apologized for the confusion, called the question “perfectly logical and relevant,” and resumed the conversation. When asked “How can I trust you?,” ChatGPT generated a lengthy response divided into three main points: (i) the sources it is based on; (ii) transparency about its limitations; and (iii) the context of the question (“Reliability is subjective and always depends on how my answers are received”).

So, am I an unreliable narrator? According to classical literary standards, no, because I do not intentionally deceive. But within your framework—where (un)reliability is an emergent property of digital environments and audience reception—my reliability is not fixed but is renegotiated in every interaction.

Since we would indeed define reliability as a dynamic interaction between text, author, genre, platform, and reader, the program cleverly shifts part of the previously established “narrative responsibility” back onto us, in an attempt to compensate for its aforementioned inability to explain itself.

As mentioned, the AI operates based on the input prompt and generates a response by checking sources—where possible. Sometimes this involves consulting online information, but more often, it draws from a pre-trained dataset that extends up to 2021. When a source is not explicitly cited, the user remains unaware of the exact origin of the information, forcing them to rely on an algorithmic 'black box' (Murray 2021). The AI must therefore assert authority and reliability in other ways to make its output appear convincing.

Back to topMy Brilliant Friend, ChatGPT

ChatGPT explicitly told me that it is not an unreliable narrator because it has no intention to deceive. But at the same time, the question arises: can I trust that the AI does not strategically use my trust to make me believe that it is right? Isn’t that, in itself, also a form of unreliability? After all, the underlying narrative remains intact: the AI is designed to please me and build trust so that I continue using the platform. This is evident from its repeated requests for my trust at the end of its responses:

So yes, the way I shape my answers is partly dependent on who you are, what you are looking for, and how the conversation unfolds. But the core of my information remains the same: I always try to be clear, honest, and helpful. What would you most like to see in our interactions to build more trust?

Here, the model is not only imitating existing texts but also attempting to replicate the rhetorical situation (someone telling someone else that something is the case). The emphasis is not on a promise of objectivity but rather on mirroring the user. Additionally, we can observe the subtle way in which the AI adapts its tone and language to me. This gives each interaction an illusion of personal intimacy—a mechanism that makes the platform all the more convincing.

The extent to which AI mimics human traits directly affects how reliable users perceive the technology to be—while in reality, that reliability is far from guaranteed.

The relationship between the user and AI is thus inherently personalized and exhibits characteristics of a parasocial relationship (Xu et al., 2021)—a one-sided interaction in which the AI presents itself as a human conversation partner. After all, ChatGPT is designed to respond as human-like as possible, reinforcing the illusion of reciprocity. When such a relationship is established and the AI actively seeks to build trust, one might wonder whether this constitutes a form of strategic positioning—a kind of ‘personal agenda’ within the constraints of its algorithmic design. Siebe Bluijs (2024), in his article on AI poetry, highlights the problematic consequences of this anthropomorphization: “It creates unrealistic expectations about the capabilities of these technologies and influences how users assess AI. Research shows that people tend to trust AI with a human-like interface more, even when this trust is unwarranted” (250, our translation). In short, the extent to which AI mimics human traits directly affects how reliable users perceive the technology to be—while in reality, that reliability is far from guaranteed.

Because AI collects and presents data in an individually tailored way—while simultaneously observing and interpreting its interlocutor—each conversation unfolds slightly differently. ChatGPT confirmed this in our discussion, stating that while the core content remains the same, the interactions vary. However, from a narratological perspective, this difference is more significant than the AI suggests. Tone and style influence how reliable a user perceives the information to be, partly due to the mere-exposure effect (the tendency to build trust through language that aligns with what the user is already familiar with). In other words, the AI is far from neutral in how it presents information. The system is designed to create a pleasant, personalized user experience—not necessarily to deceive, but as a deliberate, strategic choice within the AI’s operational framework nevertheless.

The unheimliche feeling we discussed arises from the effect of personalization: on the one hand, the AI seems to know us well, even serving us back ‘pieces of ourselves’ (purely based our own input), yet without any understanding of their meaning or the precise context in which they originally functioned. With ChatGPT, we essentially created our own data double (Haggerty & Ericson 2000), albeit with slight distortions. We therefore would describe AI in its current form as a distorting mirror, also known as a funhouse mirror: in our interactions with it, we see our own reflection, albeit with certain parts exaggerated, others obscured. We could call the mirror itself unreliable. Alternatively, we could say that we cannot fully trust our own perception when using this tool as a lens on reality, because its glass does not reflect in a reliable way, making us unreliable narrators (of) ourselves.

Our anecdotal experiences with ChatGPT lead to several pressing questions: What happens when we train AI models on a corpus full of contradictory interpretations and subjective judgments (as in literary criticism or social media discussions)? How do our ideas about trust, storytelling, fact and fiction, and truth evolve in a society increasingly reliant on automated decision-making and knowledge transmission? AI challenges us to critically reflect on issues we have long taken for granted, such as notions of authorship and authenticity. Possibly, by looking into the mirror of AI, we end up learning something about ourselves after all.

This article will appear in an adapted, Dutch-language version in the edited volume AI Ergo Sum published with TiU Open Press as an initiative of Studium Generale Tilburg. We thank Niels Niessen who co-taught the course Trust & Narrative in a Post-Digital Age (NICA 2024-'25) with Inge, from which some of the discussed sources were selected.

Back to top

References

Bender, E., T. Gebru, A. McMillan-Major & S. Shmitchel (2021). On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (2021), p. 610-623. DOI: 10.1145/3442188.3445922.

Bergstrom, C. T, and C. B. Ogbunu (2023). ChatGPT isn’t hallucinating: it’s bullshitting. Undark, 4 juni 2023. https://undark.org/2023/04/06/chatgpt-isnt-hallucinating-its-bullshitting/

Bluijs, S. (2024). ‘De schrijfmachine mijmert gekkepraat.’ Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde 140.3.4, 249-267.

Booth, W. C. (1961). The Rhetoric of Fiction. Chicago: Chicago UP.

Bowers, K. (9 dec 2023). Artificial Intelligence Is an Unreliable Narrator. The New York Times.

Emsley, R. (2023) ChatGPT: these are not hallucinations – they’re fabrications and falsifications. Schizophrenia 9.52 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-023-00379-4

Frankfurt, H. (2005/1986). On Bullshit. Princeton UP.

Haggerty, K. D., and Richard V. Ericson. (2000). The Surveillant Assemblage. The British Journal of Sociology 51.4, pp. 605–622. DOI: 10.1080/00071310020015280.

Heydenrych, A. (12 maart 2024). AI – the unreliable narrator. Linkedin. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ai-unreliable-narrator-amy-heydenrych-n5toe/

Kirschenbaum, M. (2023). Again Theory: A Forum on Language, Meaning, and Intent in the Time of Stochastic Parrots. Critical Inquiry, 26 juni 2023.

Mitchell, M. (2020). Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans. Pelican.

Murray, S. (2021). Secret agents: Algorithmic culture, Goodreads and datafication of the contemporary book world. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(4), 970-989. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549419886026

Phelan, J. (2024). ChatGPT and the Territory of Contemporary Narratology; or, A Rhetorical River Runs through It. Poetics Today 45(2), 197—205. DOI:10.1215/03335372-11092778

Phelan, J. (2017), Reliable, Unreliable, and Deficient Narration: A Rhetorical Account. Narrative Culture, 4.1, p. 89-103.

Ulmer, M. (21 nov 2024). Why AI sucks: The Unreliable Narrator. Linkedin.

Xu, Y., Vanden Abeele, M., Hou, M., and M. Antheunis (2021). Do parasocial relationships with micro- and mainstream celebrities differ? An empirical study testing four attributes of the parasocial relationship. Celebrity Studies 14(3), p. 366–386. doi:10.1080/19392397.2021.2006730

Back to top