2020: A Greek script Odyssey

A kind of lookalike English came about as a necessity for Greeks to adapt to the changes brought on by a digitalized world. To this day, "Greeklish" stirs public debate about the necessity to preserve and conserve cultural heritage.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The present stage of globalization moves at high speed. Every small or big reality wants to be involved, even at the price of recreating its own language. This article will explain why a lookalike English language within the Greek society is used and how it came into being. The difference between a lookalike English language in the Greek society and other ways of transliteration will also be described in this article. Besides illustrating the historical and critical perspectives on its use, it will be explained how each of this perspective deals differently with the political debate and historical heritage.

The tremendous spread of information and communication media has had a large impact on the conversation patterns used in our every-day lives. Email and SMS are only a few of the textual communication channels that have come up to complement, or in some cases to replace, more typical means such as the voice and the telephone (Chalamandris, Tsiakoulis, Giannopoulos, & Carayannis, 2004). The expansion of the use of the internet is a desirable process with many benefits such as ease of communication among people, expansion of commercial activity through e-commerce and much higher degree of the availability and dissemination of information across the world.

But this process is rendered somewhat more complicated when the languages used are written in ways standard computers and softwares cannot handle. Statistics on internet usage by language shows that 29.5% is English and 70.5% is non-English. As the non-English web usage increases, there is an increasing number of non-English queries that need to be handled by the search engines (Lazarinis, Vilares, & Tait, 2007). The ASCII alphabet supports only the Latin alphabet character set, internet users from countries that use a non-Latin alphabets such as Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Cyrillic, Chinese or Japanese are therefore forced to transliterate their phrases by using Latin characters only. For instance, a Greek-speaking user could receive an email in Greek written with latin characters and still be in need of a translation because of the lack of an established alphabet for writing in Greek when using computer characters.

The form of writing the Greek language in Latin characters is commonly called “Greeklish” (Karakos, 2003), although to describe it as a lookalike English might be more accurate (Blommaert, 2012). It is important to make a distinction between Greeklish and other kinds of alphabet transliteration such as Chinglish. Chinglish is an English slang that is infuenced by Chinese, whereas a lookalike English in the Greek context is a matter of script. This means that random signs are being combined into signs that are linguistically entirely meaningless, but suggest "Englishness" because they are written in Latin alphabet, Greek language material is converted into lookalike English, for example, Greek is scripted in an alphabet associated with English (Blommaert, 2012).

Over time a transliteration method has been created to supply to the lack of an established alphabet for Greek characters, which is different from any other alphabet. This lookalike language is used when writing with computers, converting Greek letters with the most similar letter of the Latin alphabet. After globalization and the development of many technological products, people are using lookalike English as it is faster for its users and also they do not have to make corrections if an orthographical mistake occurs. The way in which Greek is translated from a lookalike English to Greek and vice versa will be explained later in this article.

Lookalike English in the Greek society is extensively used in emails and in chat groups, as much that it tends to become a script register among young people. The issue of language has long been a minefield of confrontations and conflicts within Greek social and political life. The duration and intensity of those conflicts are not about issues of a language as such, but ideological, social and political questions which were at stake in critical periods of Greek history (Koutsogiannis & Mitsikopoulou, 2017).

Back to topGreece as the Cradle of the Western Culture

Greece is commonly defined as ‘the cradle of Western Culture’. This country was the first in creating the concept of a society that is supported by different institutions and producing culture in different forms such as philosophy, literature, mythology, historiography and dramaturgy (Adhikari, 2019). For those reasons, the Greek one is defined as the first form of civilization as we still intend it, inspiring all the ones that followed. Furthermore, Greek as a language is defined as ‘the source and mother of other languages’.

In the pre-classical era, poetry was created as an instrument for storytelling, starting as an oral tradition and turning into a written form afterwards. Myths and legends were the subjects of those products made of words (Mark, 2013). The Ancient literature of the pre-classical era, for instance, comprises two of the milestones of classic literature which consequently shaped the concept of the novel as we still intend it today: the Iliad and the Odyssey. Those two masterpieces are representative of the culture and tradition of Greece. The first book tells about the war of Troy, when the second book describes Odysseus ten years’ trip back home at the end of it. Besides the historical background, the characteristics of these poems entail the richness of the Greek language. The metric used to compose the two epic poems represents a marvellous game of words, based on the quantitative meter of classical epic poetry, which was successively adopted in the classical poetry of Western tradition.

The colonial migrations of the Archaic period had an important effect on its art and literature. The spread of Greek styles far and wide encouraged people from all over to participate in the era’s creative revolutions (History.com, 2019). The Greek language was also responsible for diffusing the Catholic cult, not only because of the expansion of the empire over time, but also because of the literary tradition. In fact, most of the biblical books of the New Testament were written in Greek, highlighting the prestige of the language as the one responsible for spreading the very first concept of culture.

Already in the first century BC, a ‘linguistic schism’ distinguished between written and spoken Greek. The written language, used by the intellectuals of the age, ignored the spoken language, regarding it as the result of a process of corruption and thus inferior to its ancestor, and sought to imitate classic Attic Greek language (Koutsogiannis et Mitsikopoulou, 2017).

In the 19th century, Katharevousa has been established as the national language of Greece, aiming at linking ancient to modern Greek in a modern society. This decision also shed light on the national orientation towards Europe, also considered the high regard for the ancient Greek heritage. The outcome of this decision was a diglossia, a term which defines the existence of two languages used for two different purposes in the same country. Those are Katharevousa (καθαρεύουσα), the language of administration and education closer to ancient Greek, and Demotiki (δημοτική) demotic Greek as a variation for the spoken language. In 1982 the orthographic reform revised the polytonic system of the ancient language, reducing its three accents to only one, resulting in a monotonic language. As this choice was threatening to be only the beginning of a process of abandoning the Greek alphabet it met resistance and still holds the refusal of those who perceive it as a betrayal to the tradition of the nation.

Language is influenced by its historical tradition, resulting in the creation of ways of saying and rhetorical figures which define it as a unique way of saying something while revoking national and historical landmarks. The action of speaking a language is a mean to express a view to whom can understand the words in the socio-historical context the words are spoken; the act of using it defines us as specific historical and socio-cultural subjects (Koutsogiannis et Mitsikopoulou, 2017). The loss of the language is therefore perceived as a loss of historicity and concept of nation.

Back to topLookalike English as an Online Phenomenon

The worldwide spread of information and communication had a large impact on human lives. It enables users to read and send messages with a click of a button. However, the online world is not new, it is very real and it exists with its own features and dynamics independently from the offline world. New communities and practices are developing, resulting in new forms of languaging such as the transliteration of Greek.

The online world is a public space, it is a socially constructed phenomenon (Kroon, 2019). According to Blommaert (2012), messages in the public space are never neutral, they always display connections to social structure, power and hierarchies. Displaying Greek as a lookalike English on online platforms is currently a rule of thumb, there is no social structure, control and surveillance for displaying this underdeveloped language online and offline. Making use of online platforms had barriers for people in groups that use languages such as Greek. Computers could not process Greek letters, through limitations in the early technological development (Lazarinis, Vilares, & Tait, 2007). The direct response for the problems that are caused by a lack of a formal and standardized approach to communicate the Greek language online is using Greek as a lookalike English.

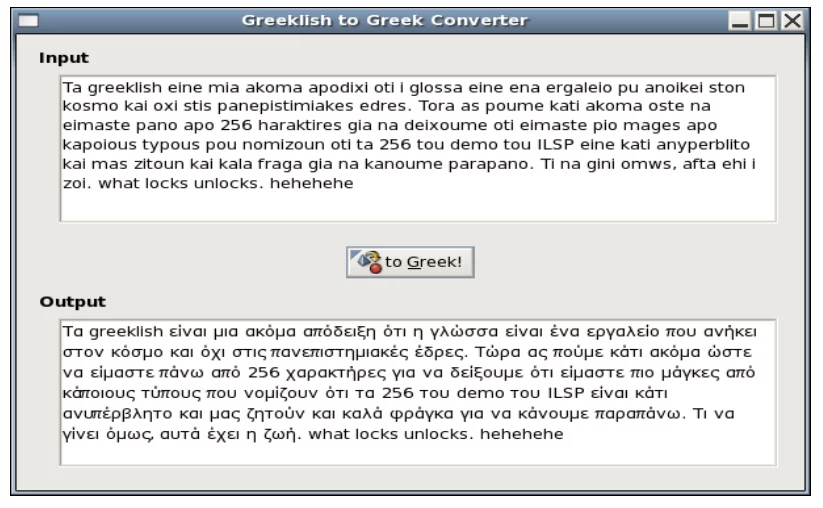

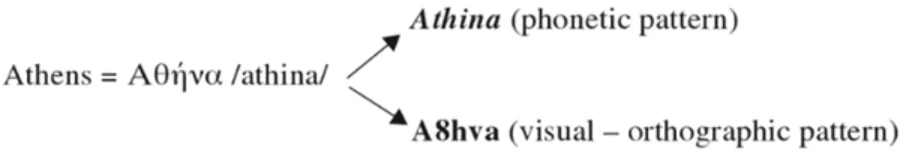

Because this lookalike language is mainly based on rules of thumb, there is a huge variety of ways in which it is written and as much inconsistencies in its use. There are two main approaches of translating Greek to a lookalike English that can be distinguished, being the first a phonetic approach and the second a visual or orthographic approach. The first approach relates to phonetics, a branch of linguistics that focuses on how the sounds of words is produced and classified. When it comes to the production of speech, this depends on the interaction of different vocal organs, for example the lips, tongue and teeth, to produce particular sounds. The second approach is related to orthography, which is the study of the practice of correct spelling according to the established usage. In a broader sense, orthography can refer to the study of letters and how they are used to express sounds and form words (Nordquist, 2019). To fully understand the difference between the phonetic and the orthographic approach, one could use the greek grapheme <η> (eta) as an example. The phonemic value of this letter is /i/ and results in the phonetic transliteration <i>, while it results in the orthographic (visual) representation <n>. Another example is the grapheme <β> (Beta, /v/) resulting in the phonetic transliteration <v> and the orthographic representation <b> (Androutsopoulos, 2009). In the image below, the transliteration of the word Athens (Αθήνα) is visible, resulting in Athina and A8hva.

The decision of writing in lookalike English in either a phonetic or orthographic way depends on who writes. There are no rules that describe how to use lookalike English in the written context. The complexity becomes salient when the Greek word διεύθυνση (address) is transliterated. Transliterations made by different people resulted in twenty-three different latin versions, each word differed in the transliteration of the Greek graphemes <ευ>, <θ>, <υ>, <ν> and <η>. Three versions were used by more than seven users being diefthinsi, diey8ynsh and dieuthinsi. The remaining translations showed forms as dieu0unsh, dieu8uvsn, dievthinsi and dief8hnsh.

Not only digital limitations were causing lookalike English to emerge. It seems that the Greek alphabet had already started losing ground in the environment of technological developments, where for everything to happen quickly in the simplest way possible is a must. With this trend came the use of Greek as a lookalike English. It could at first be seen in mobile phones and internet use, since it was easier and quicker to write with Roman characters: less letters are used and hence there is relatively more writing space; as there are no grammar rules, the writing becomes a faster procedure.

The trend started from young generations, but today lookalike English is also used by the elders. There has been a huge debate about whether or not the Greek language is in danger due to the increasing use of lookalike language in everyday life communicative situations. On the one hand, there is a group supporting the historical value and nature of the Greek spelling as it deeply embodies the roots and meaning of each word. On the other hand, advocates of lookalike English claim that a language must serve the needs of the people who use it. The internet requires quick actions and an easy way of writing. Language is a living organism which keeps on evolving. This condition has to be taken into account, without being stuck to the past (Omilo.com, 2019).

Back to topPublic debate

Because of the cultural heritage of Greece, Greek also emerged as a language. Throughout history this language has been under debate. Together with the current global orientation of Greece, the presence and debate around lookalike English is still present and still relevant (Koutsogiannis & Mitsikopoulou, 2003). This means that lookalike English is not only a vernacular, a digital phenomenon or a historical development of language, but also a phenomenon of socio-political debate in Greece.

Blommaert (2012) explains that changes in a complex system such as society are normal and normally coexist. Different historicities and different speeds of change will occur in synchronic moments. Long histories on the one hand are blended with short histories on the other. Blommeart (2012) defines this as layered simultaneity, describing it as the resources are used in the communicative context which have different background and thus different indexical loads. In the political debate one could argue that there are three different elements, being Greek, lookalike English in Greece and the rise of the computer that all have to be syncronized, causing a debate on what indexical meaning to apply or to follow. The debate divides the entire country in three camps with different perspectives on the emergence and existence of lookalike language, being a retrospective, a prospective and a resistive perspective (Koutsogiannis & Mitsikopoulou, 2017).

The retrospective point of view looks back at history and argues that the Greek language must be preserved and protected and therefore lookalike English should not be accepted in Greece. Technologies and globalization threaten to be the reason for the loss of the Greek language, meaning that a bit of the gloriousness and richness of history would be lost (Koutsogiannis & Mitsikopoulou, 2017). Because of the prestige the Greek heritage had over time and of the literary tradition dear to the nation, lookalike English constitutes a threat to the pride of the country, which feels attached to its cultural roots and therefore does not want its language to be altered and consequently forgotten. Danet and Herring (2007) argue that this perspective is not only there to preserve and nurture Greek society, but also to stop the influence of globalization or, even more, the Americanisation.

The prospective standpoint looks at the future instead of looking back. This view is not as negative towards globalization and technologies as the first one. This perspective sees lookalike English in Greece as a phase in between periods that is useful because not all technologies are fully adapted to the use of Greek. In the prospective view, the current phase of globalization is seen as a transitional phase, in which globalization becomes glocalization (Koutsogiannis & Mitsikopoulou, 2017; Danet and Herring 2007). This means that new global phenomenon are adopted in the local context, without losing a part of tlocal identity (Gobo, 2016).

The resistive perspective considers Greece as part of the European Union and its necessity in the use of English. Greeks who defend this perspective see English as a dominant force on the internet that suppresses small languages (Koutsogiannis & Mitsikopoulou, 2017). This leads to the notion that it is better for Greece to keep away from globalization and technology.

The view adopted by the Academy of Athens considers lookalike English as a threat to the Greek language. In January 2001, the Academy of Athens expressed its concern about the increasing rise of Greeklish and the possible substitution of Greek characters by the Latin alphabet, as a result of the increased use of lookalike English via internet.

Also, it cogitates a issue of negligible significance, a transitory phenomenon which will disappear as technology advances. There is a need to investigate globalization and the role of English related to the future of so called weaker languages and communication on the internet (Koutsogiannis & Mitsikopoulou, 2017).

Back to top

References

Adhikari, S. (2019). The 10 Oldest Ancient Civilizations That Have Ever Existed.

Blommaert, J. (2012). Chronicles of complexity Ethnography, superdiversity, and linguistic landscapes. Tilburg: Tilburg University.

Blommaert, J. (2012). Lookalike Language. Cambridge Journals.

History.com. (2010). Ancient Greece.

Mark, J. J. (2013). Ancient Greece.

Nordquist, R. (2019). Definitions and Examples of Orthography.

Omilo.com (2019). Writing Greeklish or using the Greek Alphabet?

Back to top