Digital exclusion of the homeless in America: COVID-19's impact

Many homeless people in the U.S. could not receive their stimulus checks due to COVID-19 restrictions, such as the closing of public spaces with internet access. How can they be digitally included in the midst of a pandemic?

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

On a given night, over half a million people experience homelessness in the United States of America, which roughly translates to around 0.17% percent of the population. This percentage has risen ever since the COVID-19 crisis, whose economical consequences made tens of thousands of citizens homeless or financially unstable. The financial crisis is "the worst global economic crisis since the Great Depression". To support the economy, the U.S. government has made the decision to send out “stimulus checks”, where taxpayers get sent $1400. For most citizens, this process was done automatically, as all information was registered online

already. For people who experience homelessness, this is harder; public spaces are closed due to Covid, and a data plan or a phone even can be too expensive. Due to this, a big portion of the homeless never saw a penny of their stimulus check. People either were not aware of their right to their stimulus check, or did not have the resources or capacity to complete the process. So, how has COVID affected the digital literacy level of homeless people in the US and which recommendations/policies could be useful in digitally including them in a way that is resistant to external factors such as a pandemic?

Back to topLiteracy as

Back to topimpedement for the stimulus check

Even long before the COVID-19 crisis hit globally, there were an estimated 553 thousand people in the United States experiencing homelessness on a given night (January 2017). This translates to 17 people experiencing homelessness per every 10 thousand people, where some states have a higher rate of homelessness than others. High rates are for example found in the District of Columbia, D.C., (110) and Hawaii (51), and very low rates in Mississippi (5). All over the country, there are responses to this; there are emergency shelters and a variety of housing and services programs offered. This creates a difference in internet access, as shelters offer a stable internet connection,

as Katie Mays describes to the U.S. News: “Everything is on the internet, and that doesn’t stop if you’re poor”. program support specialist at Dignity Village, a self-run community for the homeless, also notes that many benefits or help for the homeless are now run through online portals, such as getting food stamps. Though many people who experience homelessness have a phone, most homeless owners can not afford data plans and rely on public spaces with internet access. An article in the Journal of Medical Internet Research (2018) that while experiencing homelessness, 86% of participants were able to access the internet once a week. Commonly used devices for doing so were smartphones (66%) and public computers (59%).

But now that the Coronavirus has been around for over a year, and many government-run institutions (e.g. public libraries) are closed due to lockdown, getting access to the internet when you don’t have a technical device of your own or knowledge about how to operate one is hard. Shelters are also mostly closed, as they are prioritizing COVID-19 patients. When a homeless person wants to make sure they can sleep at a shelter, they have to make a reservation online. Later, stimulus checks, which are checks sent to a taxpayer by the government of the United States to stimulate the economy, were introduced as financial aid for people who were struggling . Most U.S. citizens had no responsibility to sign up for this, except for homeless people. But again, this process was online, making it harder to sign up.

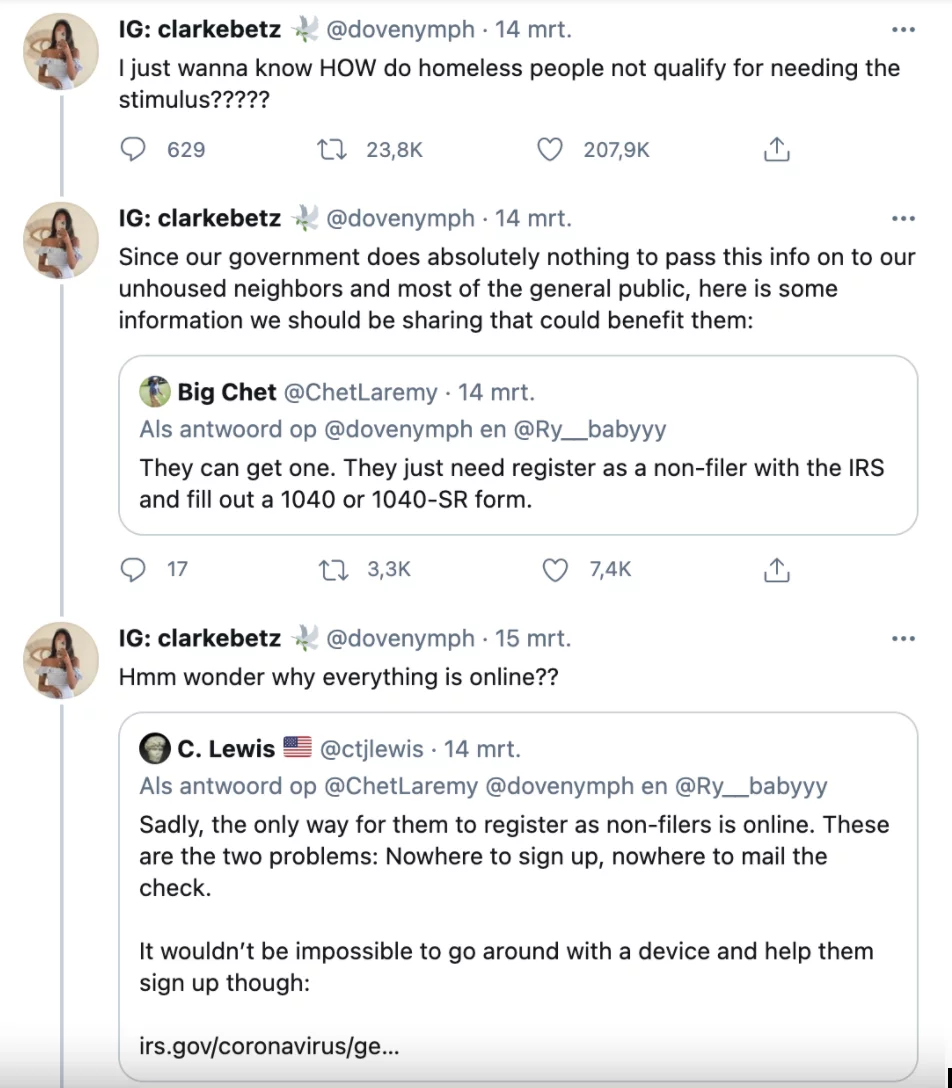

Another problem was that the check could not be mailed anywhere, as the people signing up had no individual address. Also, when stimulus checks were announced, homeless people also had the right to this check was not clear. Many homeless people were not even aware of this fact until after the stimulus checks were sent out. When multiple viral tweets about people experiencing homelessness being eligible for the “stimmy” went viral, people started to take initiative by actively helping the homeless get their stimulus checks raise awareness for the country wide problem of homelessness.

The impact of digital exclusion

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lives of homeless people in the United States form an example of how literacy can construct inequality; Many are not, or barely, able to access and/or use digital media in order to enjoy the countless possibilities they have to offer. We can observe an issue of voice here; As mentioned above, for many (social) services the use of the internet is seen as normative, making it a prestigious linguistic resource (Blommaert, 2005). While many homeless people in the United States were able to access the internet occasionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced another form of inequality due to the inaccessibility of digital resources in public spaces. Because of this, many homeless people are struggling to communicate about this issue themselves, and to fully enjoy the social benefits offered through digital media.

The pandemic’s major impact on the accessibility of digital infrastructures to homeless people in particular has serious socio-economic consequences that reinforce their already socially underprivileged position. This unequal accessibility, or perhaps sometimes even inaccessibility, to digital infrastructures falls under what Ragnedda and Mutsvairo (2018) call the ‘first degree of digital exclusion’, which is based on the possession of, or access to information and communication technologies (ICTs) and the internet. Someone can generally be considered digitally excluded when they are not able to access and use ICTs. These technologies can include features such as the internet, relevant content and services, and education for the digital literacy skills needed in order to effectively use digital technologies (Ragnedda & Mutsvairo, 2018).

The possession of, or access to the Internet and ICTs is not the only which digital exclusion is based. Ragnedda and Mutsvairo (2018) formulate three degrees of digital exclusion. The first, as mentioned already, has to do with possession of and access to ICTs. The second degree of digital exclusion has to do with inequalities in the use of ICTs. Finally, the third degree of digital exclusion concerns the social benefits and tangible outcomes users can gain from access to and use of ICTs (Ragnedda & Mutsvairo, 2018). Age- and geography-related factors or the (lack of) digital infrastructures in certain areas can also influence whether someone is digitally excluded or included (Spotti, personal communication, February 8, 2021).

So why is digital inclusion so important on a societal level? In short, digital inclusion plays a big role in whether people can fully participate in a "digitally enabled society" where all kinds of services, opportunities and knowledge are increasingly moving into the digital realm - a society that functions in an online-offline nexus. Ragnedda and Mutsvairo (2018) suggest that an increase in accessibility of ICTs and the internet could be a good starting point in moving towards a society where all members can be digitally included.

However, it does not necessarily help everyone to fully appreciate the opportunities and advantages that come with being digitally included. Rather, a proficient level of digital literacy is the most important key for digital inclusion (Ragnedda & Mutsvairo, 2018). More specifically, they argue that it is absolutely crucial to invest in “infrastructures and technologies to expand the possibilities to access the internet and provide enough training and support for the digital skills required in an advanced digitally literate society” (Ragnedda & Mutsvairo, 2018). Blommaert (2020), when addressing the issues of new technologies in society, provides a similar answer and suggests that education about and through media is very important if we want to use these technologies in a way that will benefit society (Blommaert, 2020).

Back to topHigh prices slow connection

When analysing the digital exclusion homeless people experience, we are actually looking into the effects of digitalisation on the deviant. The simplest view of deviance is essentially statistical, defining as deviant anything that varies too widely from the average (Becker, 2008). As stated above, having access to the internet has become normative. A preferably 24/7 possession of a mobile device gives us full access to society.

According to the Pew Research Center, 93% of American adults use the internet, while in early 2000 it was only half of all adults. A noticeable increase is the age group 65+: only 14% of this target group used the internet in 2000, which has increased to 75% in 2021. As of January 2021, there were approximately 269.5 million mobile internet users in the United States, representing over 90 per cent of all active internet users nationwide (Statista, 2021). According to BroadBand Search, the average price of an internet connection in the United States is 61.07 dollar, which is more expensive than any European country.

Microsoft studied the number of citizens who own broadband internet connection (which is the least amount of speedy and reliable internet connection you will need to survive today’s fast-paced digital world), and came to the conclusion that 160 million Americans - 70% of the internet users - are without the needed connection simply because it is too expensive for most people (Smith, 2018). This results in a quarter of Americans cannot afford to go online to pay certain bills, apply for jobs or join a zoom call for study. The high cost of broadband is mainly due to the lack of competition that leads to high prices. 70% of Americans have either zero or just one option for broadband providers; for a competitive and free market, there should be at least three different options. America is also lacking a proper infrastructure that is needed to get broadband internet to all places (Broad Band Search). The internet has ‘out speeded’ the States.

The Microsoft analysis also includes county unemployment data, which points to the strong correlation between joblessness and low rates of broadband use. Brad Smith, president of Microsoft, said: “The worst place to be is in a place where there is no access to the technology everyone else is benefiting from”. People who do not have this enormous access to the digital world, are left out and a large step behind on the social and professional ladder.

Back to topSeeking for solutions

Regarding the policies surrounding the inaccessibility of ICT services by the poor and displaced members of the United States, there are some general changes that could be made. For instance, the inability to apply for the stimulus check without internet access should be revised. As a general rule, inhabitants of the country eligible for the benefits should not be digitally excluded due to circumstances often out of the individuals’ control. Since this would tackle one, if not two of the three degrees of digital exclusion as described by Ragnedda and Mutsvairo (2018). With those restrictions taken away at least users that still might not be able to access ICT technologies, because of income or housing issues, can still apply for the stimulus package through traditionally offline means.

The challenges that surround digital literacy are in this case largely avoided because of the ability to simply walk up to a regional governmental facility and go through the process of applying for the said benefit. Another possibility would be the crucial need to provide and expand access to the internet for the populace and especially those financially and locationally indisposed.

With the normative nature of the internet as an indisputable part of our daily lives, infrastructure at a relatively high cost. Especially in our case as we look towards the United States, we see that rising costs of data plans, through monopolized infrastructure is stumping the growth of the internet. Of course, broad band internet is generally hard to acquire when one is without a house. But as the data shows us most homeless people will be able to access the internet once a week through a smartphone or public computers, the first mostly becoming more expensive and thus harder for people to keep using, and the latter is being closed or stricter because of the current COVID-19 protocols in place. (, 2018)

This ties in directly to the Digital Exclusion and the fact that the pandemic impacts on a major scale the accessibility of digital infrastructure for those that are already struggling. So, the need to house COVID-19 patients and to social distance people, . For instance don’t make it so that homeless people have to have access of the internet beforehand to even reserve a spot, create an offline list where people can physically enter their information or reserve a spot on the local computer. Most of these systems are a great example of bureaucracy and the npush for everything to go digital, almost seen as deviants by not participating in this digitalization of our society, when in fact they are not even able to do so because of the many forms of digital exclusion they face.

If the issues of digitalization benefit one part of society but exclude another part of society, how can it still be a net gain to our growth? Like Blommaert mentions (2020) for a technology to be normative and beneficial to us as a society, we must be critical in addressing the issues and while he also says that education about and through the media is essential, we believe that without access to said technology, part of the society will not be able to grow and benefit from it. Which leads us right back to the importance of digital inclusion in our society, and especially during this pandemic.

Back to topReferences:

Becker, H. S. (1997). Outsiders: Studies In The Sociology Of Deviance (New edition). Free Press.

Blommaert, J [JanBlommaert]. (2020, June 19). Jan Blommaert on “Old new media” [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BDRFyXkCaLo

Blommaert, J. (2005). Language and inequality. In J. Blommaert, Discourse: a critical introduction 2005 (pp. 68-96).Retrieved fromhttps://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uvtilburg-ebooks/detail.action?do…

Ellis, E. G. (2021, January 28). The Lasting Impact of Covid-19 on Homelessness in the US. Retrieved fromhttps://www.wired.com/story/covid-19-homelessness-future/

Grant, J. (2020, May 21). City Bar Sizes Up Lack of Internet Access at Homeless Shelters. Retrieved from https://www.law.com/newyorklawjournal/2020/05/20/city-bar-sizes-up-lack…

Halton, C. (2021, March 19). Stimulus Check. Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/stimulus-check.asp#:%7E:text=A%20s…

How Do U.S. Internet Costs Compare To The Rest Of The World? (n.d.). BroadbandSearch.Net. https://www.broadbandsearch.net/blog/internet-costs-compared-worldwide

Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet. (2021, April 7). Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/

Leins, C. (2018, April 26). Wi-Fi Hot Spots Help Homeless Get Back on Their Feet. Retrieved from https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/2018-04-26/internet-ac…

Lohr, S. (2018, December 5). Digital Divide Is Wider Than We Think, Study Says. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/04/technology/digital-divide-us-fcc-mic…

Ragnedda, M. & Mutsvairo, B. (2018). Digital Inclusion: Empowering People Through Information and Communication Technologies. Retrieved from https://tilburguniversity.instructure.com/courses/5338/modules

Smith, B. (2019, January 11). The rural broadband divide: An urgent national problem that we can solve. Microsoft On the Issues. https://blogs.microsoft.com/on-the-issues/2018/12/03/the-rural-broadban…

Statista. (2021, March 4). United States: digital population as of January 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1044012/usa-digital-platform-audien…

The State of Homelessness in America. (2019, June 27). Retrieved from https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statis….

VonHoltz, L. A. H., Frasso, R., Golinkoff, J. M., Lozano, A. J., Hanlon, A., & Dowshen, N. (2018). Internet and Social Media Access Among Youth Experiencing Homelessness: Mixed-Methods Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(5), e184. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9306

Back to top